What is Protein Crystallography?

Protein crystallography is a technique used to determine the three-dimensional structure of proteins. It involves crystallizing proteins into ordered lattices and analyzing the resulting diffraction patterns from X-rays. This provides detailed information about the protein's atomic structure, which helps understand its function and interactions with other molecules.

The process includes protein expression, purification, crystallization, data collection, and structural analysis. X-ray crystallography is the most common method, accounting for about 90% of entries in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), the largest repository of protein structures. Other methods like electron and neutron crystallography are also used, with neutron crystallography offering better resolution for proteins containing hydrogen atoms.

Why is Protein Crystallography Important?

Protein crystallography is crucial in biomedical research and drug development. It helps scientists understand the 3D structure of proteins and their functions, revealing how proteins interact. This knowledge is essential for designing drugs that target specific proteins' active sites.

The technique also aids bioengineering and catalytic technology by enabling the design of more efficient enzymes or new biocatalysts. Protein crystallography is used in fields like genomics, virology, and cancer research.

However, it faces challenges, such as obtaining high-quality crystals, which depends on factors like protein concentration, pH, and additives. Data collection and structural analysis also require precise technical support. Despite these challenges, protein crystallography has advanced both basic biology and modern medicine.

A Historical View: Key Moments in Protein Crystallography

1950s-1960s: Laying the Foundation of X-ray Crystallography

In the 1950s and 1960s, X-ray crystallography was revolutionized by the work of William Henry and William Lawrence Bragg, who applied X-ray diffraction to study protein structures. In 1958, Max Perutz and John Kendrew solved the first 3D protein structures of hemoglobin and myoglobin using the Multiple Isomorphous Replacement (MIR) method, earning the Nobel Prize in 1962. The MIR technique, which involved introducing heavy atoms like mercury or platinum into crystals, helped solve the phase problem, allowing scientists to determine protein structures more accurately.

1970s-1980s: Synchrotron Radiation and the Resolution Revolution

In the 1970s and 1980s, synchrotron radiation greatly enhanced X-ray crystallography by providing high-intensity X-rays, improving diffraction data resolution and enabling the study of more complex proteins like membrane proteins. During this time, the Molecular Replacement (MR) method also emerged, allowing researchers to use known homologous structures as models, which sped up phase determination and reduced the need for heavy atom labeling.

1990s-2000s: Rise of Automation and High-Throughput Techniques

In the 1990s and 2000s, the Structural Genomics Initiative drove advances in automated crystal growth, data collection, and software development, enhancing protein structure determination. Techniques like Single-wavelength Anomalous Diffraction (SAD) and Multi-wavelength Anomalous Diffraction (MAD) simplified phase determination using labeled proteins and synchrotron radiation. Cryo-crystallography, which involved freezing crystals with liquid nitrogen, further improved data quality by reducing radiation damage.

2010s-Present: Femtosecond Crystallography and the Rise of Cryo-EM

Since the 2010s, X-ray Free Electron Lasers (XFEL) allowed femtosecond pulse analysis, enabling high-resolution studies of microcrystals like lysozyme. Cryo-EM also saw a revolution, achieving sub-3 Å resolutions after 2015, making it ideal for studying membrane proteins and large complexes. Additionally, XFEL combined with light activation techniques enabled time-resolved crystallography, capturing dynamic processes like enzyme catalysis and signal transduction.

Basic Concepts in Protein Crystallography

A. Proteins and Their Structures

Overview of Protein Structure

Protein structures consist of four levels. The primary structure is the linear sequence of amino acids. The secondary structure involves local folds like α-helices and β-sheets, which form the foundation for domain formation. The tertiary structure is the three-dimensional arrangement of a single polypeptide chain, where domains emerge, stabilized by interactions like hydrophobic forces and disulfide bonds. Finally, the quaternary structure is the assembly of multiple polypeptides into functional complexes, such as the 60S ribosomal subunit, which includes proteins and RNA for peptide bond formation.

Importance of Protein Structure in Function

Protein structure is fundamental to its biological activity, as it determines specificity, efficiency, and regulation:

- Binding Specificity and Catalysis: The active site of proteins, like the PIWI domain of Argonaute, positions metal ions for specific reactions, mimicking ribonuclease activity. Additionally, allosteric regulation in proteins like p38 MAPK shows how structural changes facilitate signal transduction and interactions with substrates like transcription factors.

- Structural Dynamics and Adaptation: Proteins such as hyperthermophilic enzymes remain stable at high temperatures due to rigid cores, while their flexible surfaces allow for efficient catalysis. Likewise, conformational changes in AAA+ ATPases (e.g., Clp proteases) illustrate how structural shifts enable protein functions like substrate remodeling.

- Disease and Mutational Insights: Mutations in proteins, such as ankyrin repeat proteins, can disrupt folding or binding, leading to diseases like cancer and neurological disorders. Evolutionary trace methods identify key residues in functional epitopes, aiding studies of disease-related mutations. Additionally, protein structures like VDAC1 provide insights for drug design, such as modulating mitochondrial apoptosis in cancer.

This illustrates how protein structure directly influences its function, enabling specific biological activities and serving as a key target for therapeutic strategies.

B. Crystallography Basics

What is Crystallography?

Crystallography is a scientific method used to study the arrangement of atoms in crystalline materials through diffraction techniques. By analyzing how crystals—formed by atoms in an ordered, repeating structure—scatter X-rays, electrons, or neutrons, researchers can determine the three-dimensional atomic or molecular structure of the material.

Key concepts in crystallography include:

- Crystal Symmetry: Crystals have specific symmetrical properties, such as rotations and reflections, that categorize them into 230 space groups, a classification first developed by Fedorov and Schoenflies in the late 19th century.

- Unit Cell: The smallest repeating unit of a crystal lattice, characterized by its lattice parameters (lengths and angles) and the positions of atoms within it.

- Reciprocal Lattice: A mathematical tool used to interpret diffraction data, linking the geometry of the crystal in real space to its diffraction patterns.

Protein crystals are fragile and radiation-sensitive, necessitating synchrotron radiation and rapid data collection. Additionally, proteins often require isotopic labeling (e.g., selenomethionine) for experimental phasing.

How Does Protein X Ray Crystallography Work?

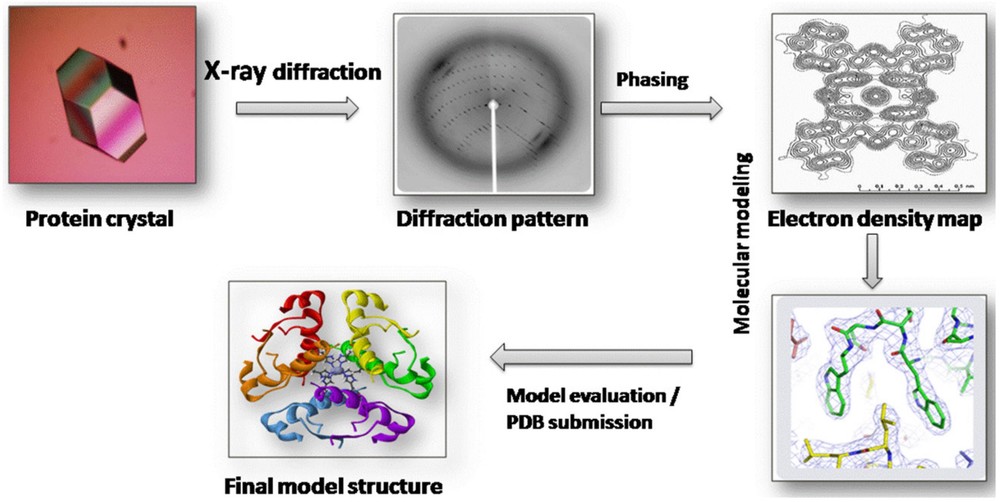

Protein crystallography works by exposing protein crystals to X-rays. As the X-rays pass through the crystal, they scatter in predictable patterns. These diffraction patterns provide information about the positions of atoms in the protein. The data is then processed to create an electron density map, which is used to model the protein's 3D structure.

Figure 1. Workflow for Protein Structure Determination by X-ray Crystallography. (Gawas U B, et al., 2019)

Figure 1. Workflow for Protein Structure Determination by X-ray Crystallography. (Gawas U B, et al., 2019)

Process of Protein Crystallography

1. Protein Purification

The first crucial step in protein crystallography is obtaining a pure protein sample. Protein purification separates the target protein from other cellular components to ensure that only the desired protein is present. This step is vital for ensuring high-quality crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis.

Methods of Protein Purification

Various chromatography techniques are commonly used in protein purification:

- Affinity Chromatography: This method utilizes specific binding interactions, such as Protein A/G for antibody purification, to isolate the target protein.

- Ion-Exchange Chromatography: Separates proteins based on their charge, ensuring the collection of a homogeneous sample.

- Size Exclusion Chromatography: Separates proteins according to their size, aiding in the isolation of larger proteins or complexes.

- Hydrophobic Charge Induction Chromatography (HCIC): A notable method for antibody purification, HCIC uses pH-dependent hydrophobic interactions to ensure high recovery rates and purity under mild conditions.

Importance of Protein Purity

Achieving high purity (above 99%) is critical for successful crystallization. Impurities can disrupt the ordered lattice formation necessary for quality crystals. Techniques like SDS-PAGE and Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) are used to assess the purity and monodispersity of the protein sample. Additionally, post-translational modifications such as glycosylation can affect crystallization behavior and should be carefully analyzed, often using mass spectrometry.

Ensuring the protein sample is pure and homogeneous is essential for obtaining well-ordered crystals, which are necessary for accurate structural analysis in protein crystallography.

Select Service

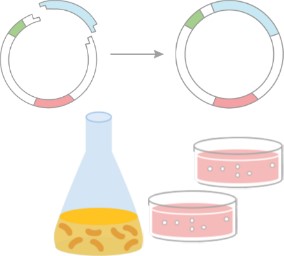

2. Protein Crystallization

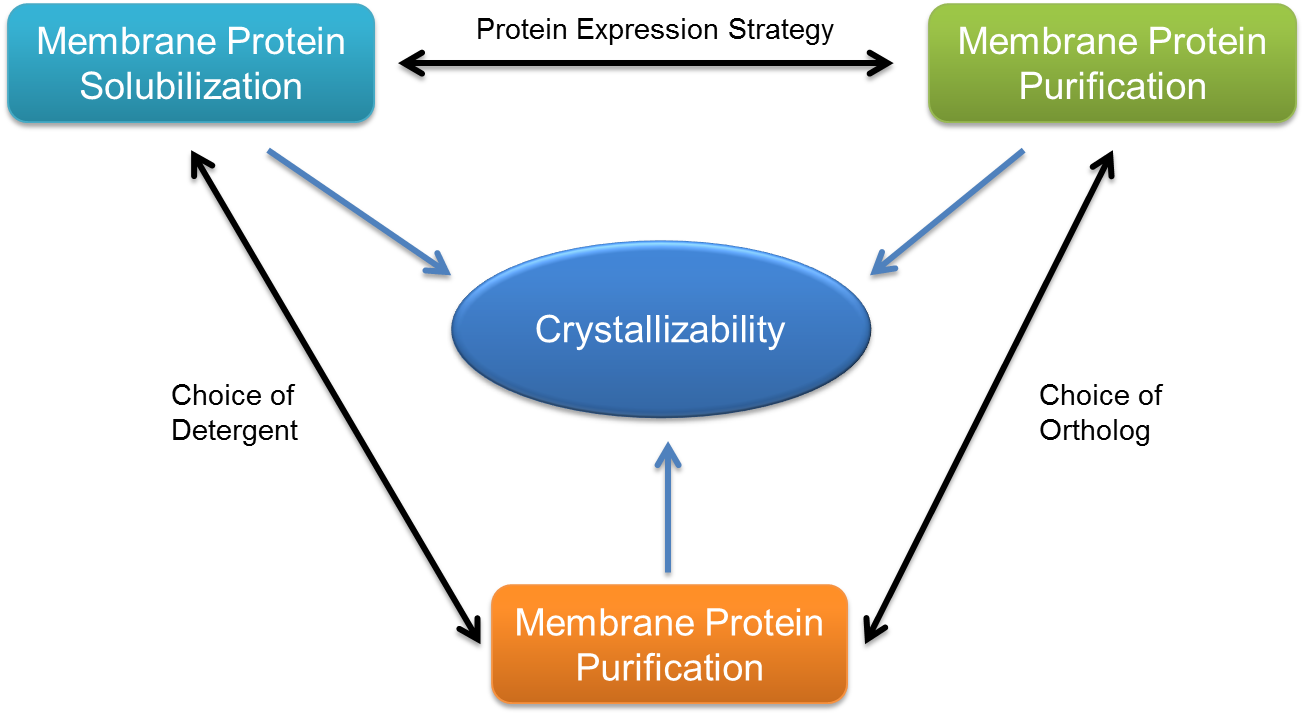

After successful protein purification, the next step is protein crystallization—forming highly ordered crystals of the target protein. Crystallization is often a challenging step, as not all proteins easily form crystals. Several methods are used to encourage crystal formation, each with its own advantages and applications.

Methods of Protein Crystallization

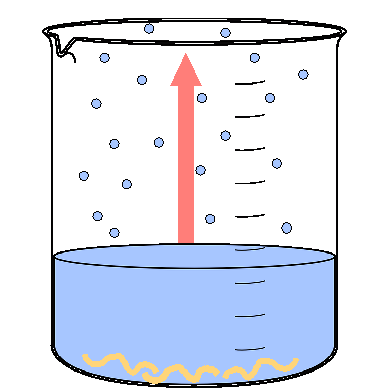

- Vapor Diffusion: This is the most common crystallization method, where a protein solution is placed in a sealed container, and water vapor gradually evaporates. The change in concentration promotes crystal formation. Innovations like 3D-printed high-density droplet arrays enable screening with very small protein volumes, significantly reducing protein consumption.

- Batch Crystallization: In this method, the protein is mixed with a precipitant in a large batch. As the solution sits, crystals gradually form over time. The success of batch crystallization depends on carefully managing supersaturation, which influences nucleation dynamics and crystal growth.

- Microdialysis: This technique involves placing the protein in a dialysis membrane, allowing it to exchange with a surrounding solution. The process is slower, but it can be highly effective for specific protein types. Recent advancements in micro-volume dialysis have significantly reduced crystallization time, with crystals forming in as little as 30 seconds.

Challenges in Protein Crystallization

- High Supersaturation: Proteins typically require higher supersaturation than small molecules to form crystals, but this can also lead to the formation of amorphous precipitates instead of well-ordered crystals.

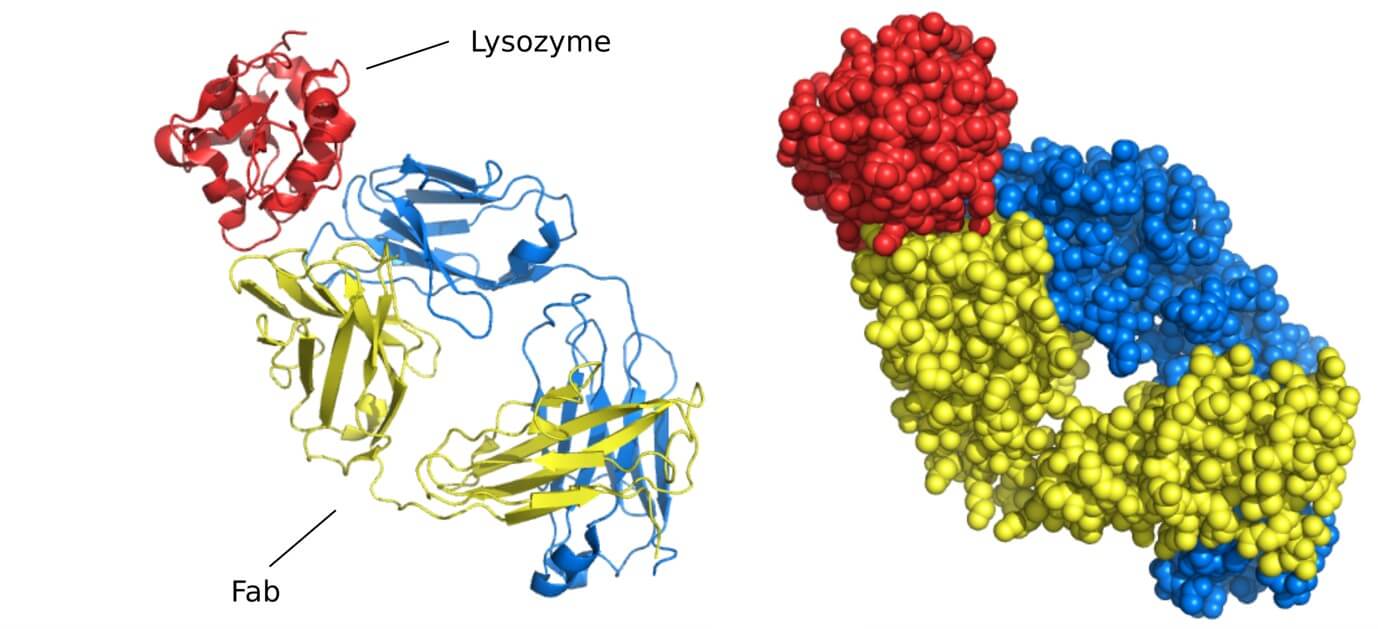

- Membrane Protein Crystallization: Hydrophobic membrane proteins are especially challenging due to their instability in aqueous solutions. To address this, detergents or lipidic cubic phases are used, which complicates the crystallization process and screening.

- RNA and Large Complexes: These types of proteins often form high-solvent-content crystals that are difficult to analyze due to weak diffraction. For these proteins, techniques like cryo-EM are often used for structural analysis.

Crystallization remains one of the most difficult steps in protein crystallography, requiring fine-tuned conditions and specialized techniques to achieve high-quality crystals.

Select Service

- Batch Screening for Crystal Production

- Crystallization Condition Optimization Screening

- Fusion Protein-Assisted Crystallization

- Crystallization with Mutant Library Approaches

- Crystallization Chaperone Strategies

- Controlled In Meso Phase (CIMP) Crystallization

- Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) Crystallization

- Bicelle-Protein Crystallization

3. X-ray Data Collection

Once high-quality protein crystals are obtained, they are exposed to X-rays to collect diffraction data, which is essential for determining their atomic structure.

Preparing Crystals for X-ray Diffraction

Crystals are soaked in cryoprotectants, such as glycerol, and rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen. This minimizes radiation damage during the X-ray diffraction. Mechanical methods, like seeding in solvent-free reactions, help generate single, high-quality crystals suitable for diffraction analysis.

X-ray Diffraction Techniques

- Monochromatic X-rays: Synchrotron radiation, which provides a consistent and intense source of monochromatic X-rays, is commonly used. When these X-rays pass through the crystal lattice, they scatter, producing diffraction patterns that are key to structural analysis.

- Bragg's Law: The relationship between the spacing of the crystal lattice and the diffraction angles is described by Bragg's Law. This allows researchers to calculate the positions of atoms within the crystal.

- Detector Advancements: The use of pixel-array detectors significantly improves both the resolution and speed of data collection, facilitating more accurate and faster analysis of diffraction patterns.

Data Acquisition and Quality Control

- Accuracy of Data: The quality of the diffraction pattern directly affects the final structural model. Key parameters such as signal-to-noise ratio and data completeness must be carefully monitored during data collection.

- Automated Data Processing: Automated pipelines like DIALS help streamline data processing, while quality control methods (e.g., reference dataset validation) ensure reproducibility and accuracy of the diffraction data.

4. X-ray Data Processing

Once the diffraction data is collected, it undergoes a series of processing steps to extract structural information from the crystal.

Processing Diffraction Data

- Spot Indexing and Intensity Integration: Software packages like HKL-2000 and XDS are used to index diffraction spots, integrate the intensity of each spot, and scale the data. This process helps in converting raw diffraction data into usable form for further analysis.

- Rietveld Refinement: The Rietveld method is applied to refine the diffraction patterns, correcting for preferred orientation and microabsorption effects. This step ensures that the data is accurately represented for model building.

Determining the Electron Density Map

- Fourier Transformation: The processed diffraction data is used in a Fourier transformation to generate electron density maps. These maps show where atoms are likely to be located within the crystal.

- Phase Ambiguity Solutions: Addressing phase ambiguity is critical, and methods like molecular replacement (using homologous models) or experimental phasing techniques such as SAD (Single-wavelength Anomalous Dispersion) and MAD (Multi-wavelength Anomalous Dispersion) are employed to solve this challenge.

- Complementary Techniques: Techniques like Cryo-EM and Iterative Helical Reconstruction (IHRSR) are often used alongside X-ray data processing to study flexible assemblies and more complex structures that may not be resolvable using X-ray alone.

Building and Refining the Model

- Model Fitting: Tools such as Coot are used to fit atomic models into the electron density maps. This process involves identifying the likely positions of atoms within the crystal.

- Multi-Scale Refinement: Techniques like EM-IMO combine homology modeling with molecular dynamics to refine side-chain conformations and improve the accuracy of the model. This helps in resolving any local mismatches and ensures a more precise model.

- Energy Function Optimization: To further enhance the model's accuracy, physical energy functions are applied. These functions simulate the interactions of atoms with their environment, including solvent interactions and backbone flexibility, improving the overall reliability of the model.

5. Structure Determination

Interpreting the Model

- Visualization Tools: Structural features such as active sites and ligand interactions are analyzed using advanced visualization tools like PyMOL and Chimera. These tools help in identifying key functional regions within the protein.

- Large Complexes Analysis: For larger complexes, techniques like 3D segmentation and coherence analysis are applied to delineate individual domains and functional motifs, aiding in the understanding of how the structure supports its biological function.

Validation and Quality Assessment

- Structural Metrics: The quality of the model is assessed using several validation metrics, including Ramachandran plots, which evaluate the geometry of protein backbone torsion angles, and clash scores, which indicate steric clashes between atoms.

- Cross-Validation: To further ensure the accuracy of the model, cross-validation is performed. This can include comparing results with other techniques like native mass spectrometry (nMS-UVPD), which can verify oligomeric states and confirm ligand binding.

Final Refinement and Confirmation

- Refinement for Precision: Based on validation feedback, the model may undergo further refinement to correct any inaccuracies or inconsistencies in the data.

- Model Confirmation: After refinement, the final structure is confirmed through comprehensive assessments, ensuring the model is both accurate and reliable for further studies or applications in drug design and other fields.

Select Service

Applications of Protein Crystallography

A. Structural Biology

Understanding Protein Function

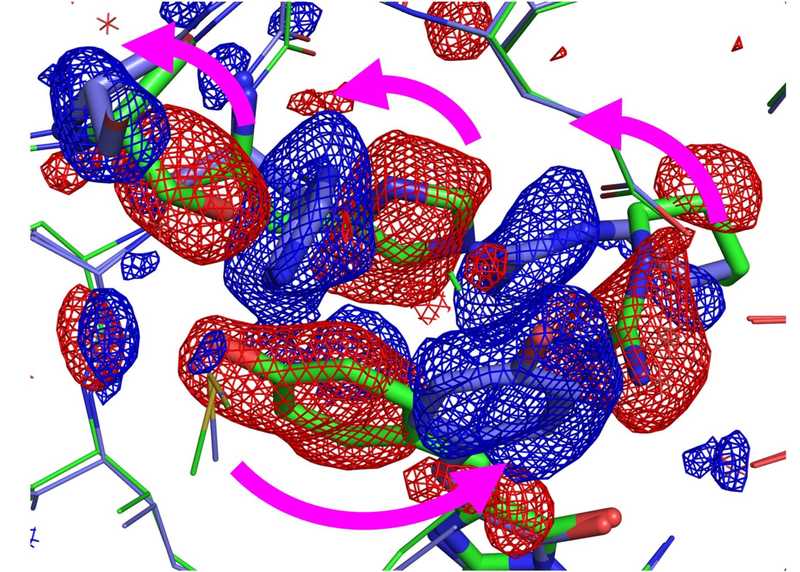

Protein crystallography provides high-resolution insights into protein structure, unveiling conformational dynamics and functional mechanisms. Techniques like XFEL (X-ray Free Electron Lasers) have overcome traditional radiation damage limits, capturing dynamic conformational changes of photo-switchable proteins, such as fluorescent proteins. This allows a deeper understanding of how light-sensitive proteins are regulated at an atomic level. Additionally, multi-dimensional crystallography using factors like temperature and ligand concentration enables tracking real-time conformational changes, such as those in hemoglobin that help elucidate allosteric signal transmission pathways. Structural analysis of complexes like the ribosome, combining X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM, has further advanced our understanding of mRNA translation mechanisms, demonstrating the core role of structural biology in studying complex molecular machines.

Figure 2. Photochromic Fluorescent Protein Skylan-NS Structure Determination by Serial Femtosecond Crystallography. X-ray crystal

structures of the Skylan-NS protein in its cis (on) and trans (off) states, obtained through serial femtosecond crystallography at SACLA and LCLS.

(Hutchison C D M, et al., 2017)

Figure 2. Photochromic Fluorescent Protein Skylan-NS Structure Determination by Serial Femtosecond Crystallography. X-ray crystal

structures of the Skylan-NS protein in its cis (on) and trans (off) states, obtained through serial femtosecond crystallography at SACLA and LCLS.

(Hutchison C D M, et al., 2017)

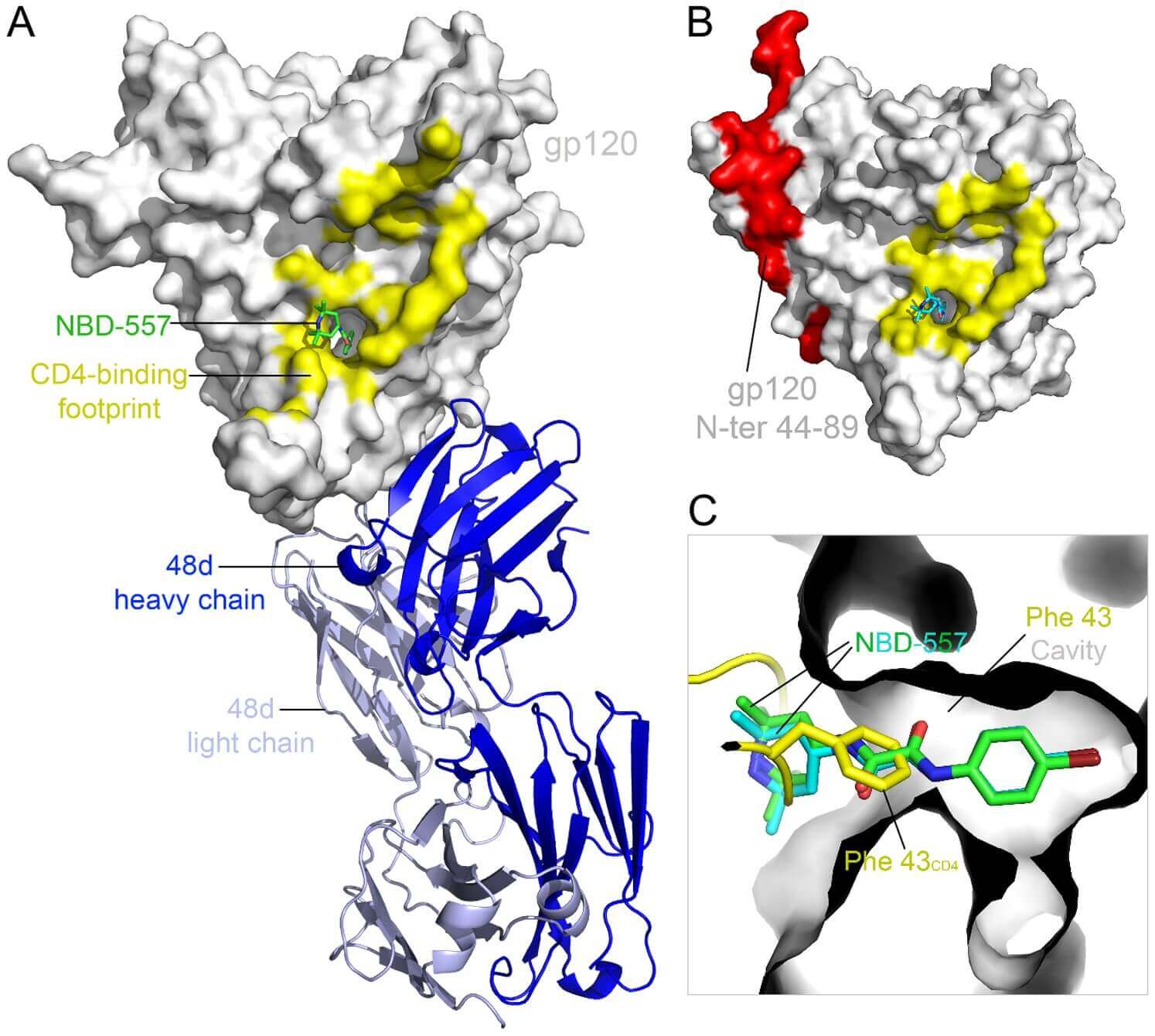

Drug Design and Development

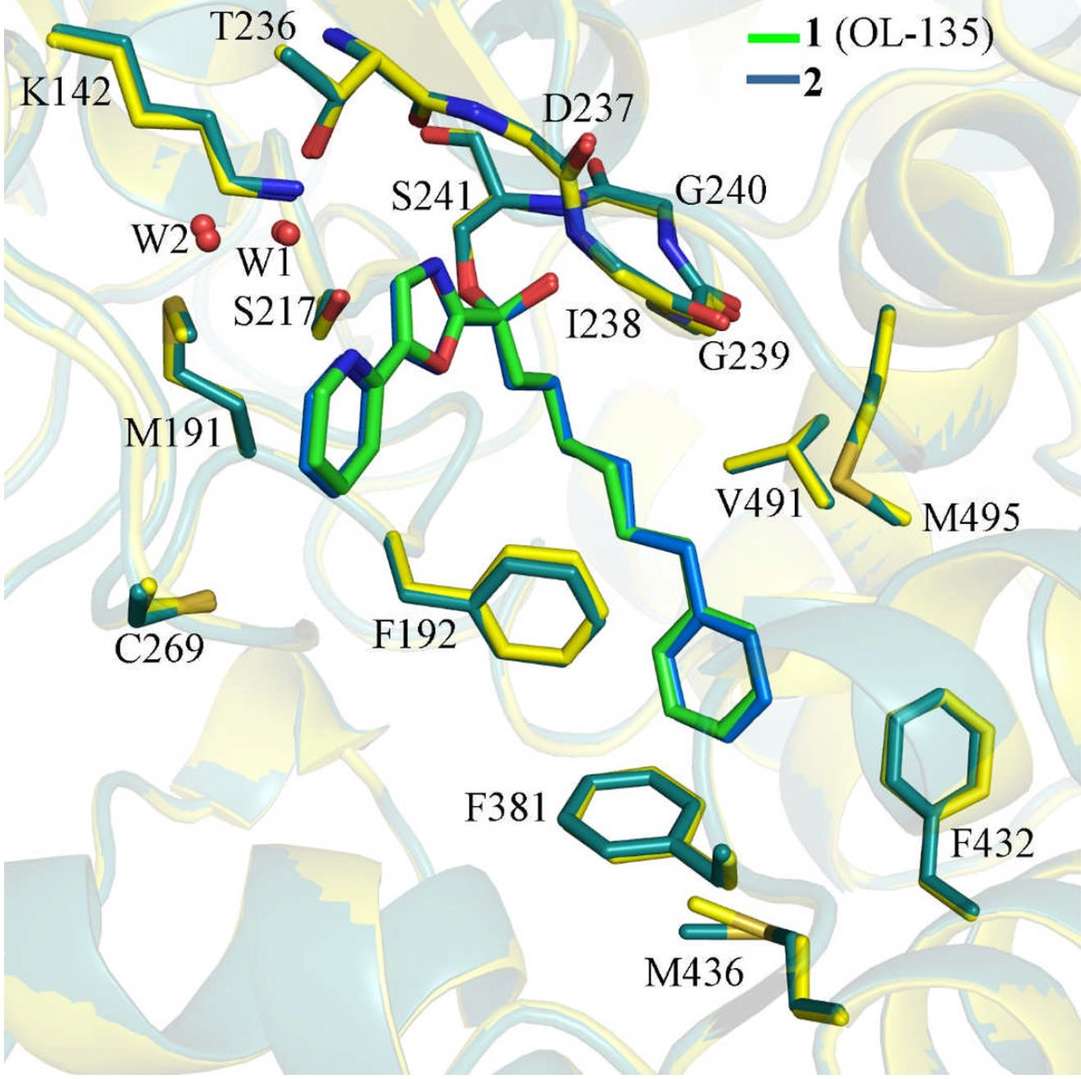

Structure-based drug design (SBDD) is a cornerstone of modern drug development. The crystallographic analysis of enzyme active sites, like that of neuraminidase for Oseltamivir, facilitates the design of potent inhibitors by mimicking the natural substrate. Crystallography has also guided the development of HIV protease inhibitors by revealing the enzyme's active site symmetry, leading to successful drug designs like saquinavir. Co-crystallization of drug candidates, such as the α-ketoheterocyclic inhibitors with FAAH, has clarified the molecular binding mechanisms and accelerated the development of treatments for metabolic diseases.

Figure 3. Superposition of co-crystal structures showing inhibitors 1 (green) and 2 (blue) bound to FAAH protein, with protein

backbones in yellow (1) and dark green (2). (Mileni M, et al., 2009)

Figure 3. Superposition of co-crystal structures showing inhibitors 1 (green) and 2 (blue) bound to FAAH protein, with protein

backbones in yellow (1) and dark green (2). (Mileni M, et al., 2009)

B. Biotechnology

Engineering Proteins for Industrial Use

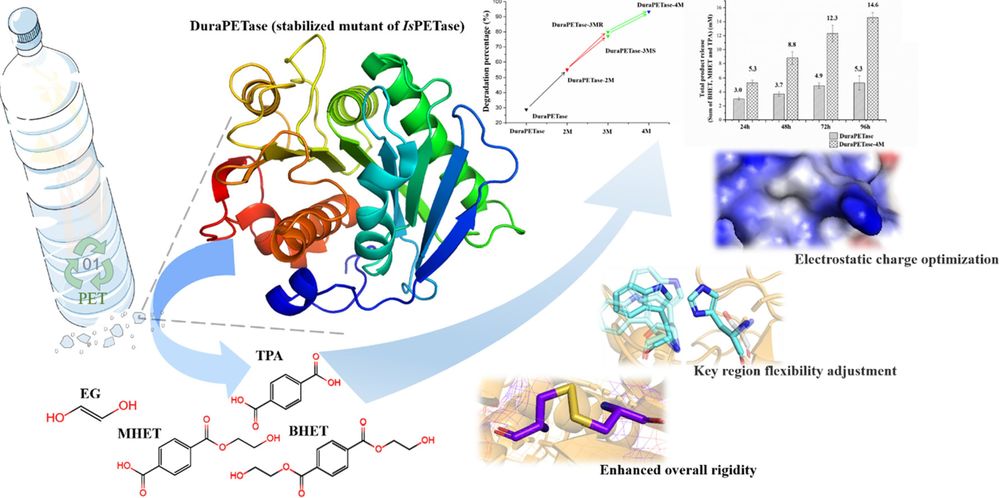

Protein engineering leverages structural insights to enhance enzymes' stability and catalytic efficiency for industrial applications. For example, DuraPETase, a PET-degrading enzyme, was engineered for enhanced thermal stability based on its crystal structure, allowing it to function effectively at high temperatures. The crystal structure of SpyCatcher and its peptide tag revealed their covalent binding mechanism, enabling optimized usage in bioconjugation technologies. Similarly, alkaline α-amylase has been engineered for increased heat stability by analyzing the hydrogen bond network in its β-sheet regions, significantly prolonging its life in industrial processes.

Figure 4. Enhancing DuraPETase's PET Degradation Capacity via Structural Optimization. Structural optimization of DuraPETase-4M through

disulfide bond formation, flexibility adjustment, and electrostatic charge optimization to improve PET degradation efficiency. (Liu Y, et al.,

2022)

Figure 4. Enhancing DuraPETase's PET Degradation Capacity via Structural Optimization. Structural optimization of DuraPETase-4M through

disulfide bond formation, flexibility adjustment, and electrostatic charge optimization to improve PET degradation efficiency. (Liu Y, et al.,

2022)

Agricultural Applications

In agriculture, protein crystallography aids in the directed evolution of enzymes for improved efficiency. Bacillus subtilis xylanase (Family-11) was engineered through structure-guided mutagenesis to increase its thermal stability by 10°C, enhancing its performance in animal feed processing. Crystallography has also been instrumental in studying plant pathogen-related proteins, such as fungal cell wall degrading enzymes, paving the way for engineering disease-resistant crops. Furthermore, structurally optimized insecticidal proteins like Bt toxins have been designed to increase specificity against pests while minimizing non-target effects.

Select Service

Related Reading

C. Medical Research

Disease Mechanisms

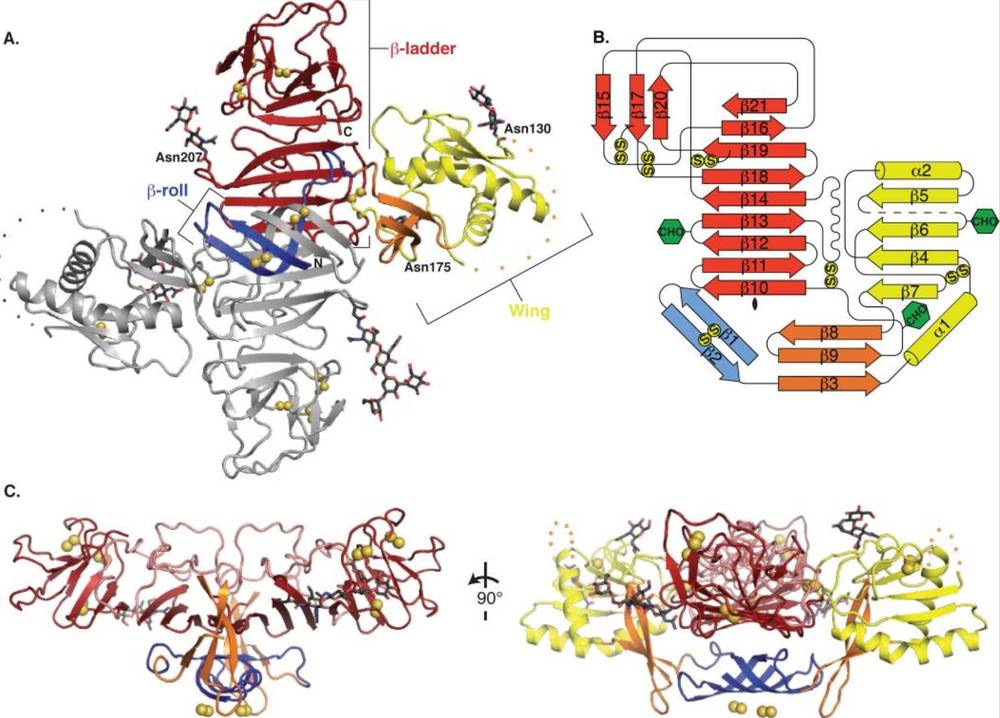

Protein crystallography plays a key role in understanding disease mechanisms, particularly in the context of protein aggregation and signaling disruptions. For instance, the crystal structure of human prion protein (PrP) fragments revealed how they aggregate through β-sheet oligomerization, shedding light on the molecular basis of prion diseases. The structure of Dengue virus NS1 protein uncovered its dual-functional surface: one side interacts with the host membrane to promote replication, while the other evades immune detection by hindering antibody binding. Furthermore, the structural study of NUDT15 gene mutations (R139C/H) and their effects on enzyme activity explained the abnormal metabolism of mercaptopurine in patients, revealing genetic insights into drug toxicity.

Figure 5. NS1 Dimer Structure and Domain Organization. NS1 dimer structure showing the domain organization, disulfide bonds,

glycosylation sites, and a disordered region. Topology and views from different angles. (Akey D L, et al., 2014)

Figure 5. NS1 Dimer Structure and Domain Organization. NS1 dimer structure showing the domain organization, disulfide bonds,

glycosylation sites, and a disordered region. Topology and views from different angles. (Akey D L, et al., 2014)

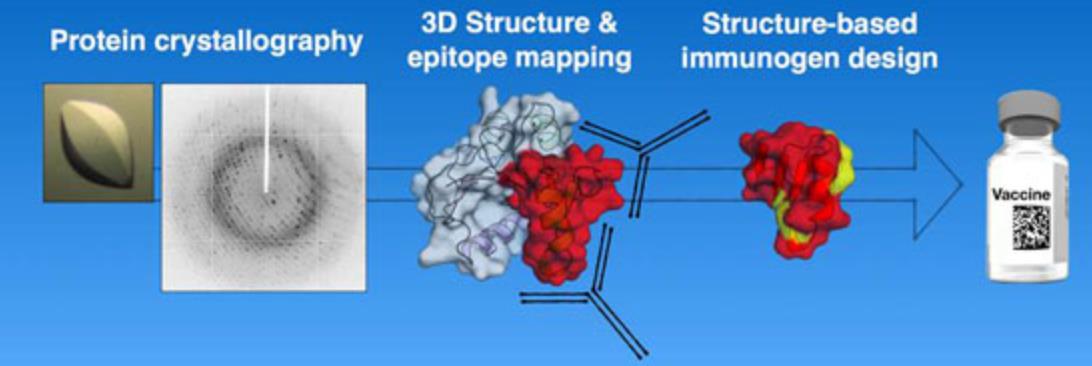

Targeted Therapies

Targeted therapies rely heavily on protein structural data for drug design. For example, the co-crystal structure of RSV F protein with neutralizing antibodies has guided the rational design of vaccines with enhanced immunogenicity. In cancer research, structural insights into EGFR domain II have led to the development of small molecule inhibitors, overcoming the limitations of traditional antibody therapies. Additionally, structural research into S100A6 and its interaction with calmodulin has facilitated the design of small molecules that block its interaction with p53, offering a potential new intervention for cancer metastasis.

Figure 6. Protein Crystallography in Vaccine Antigen Design. (Malito E, et al., 2015)

Figure 6. Protein Crystallography in Vaccine Antigen Design. (Malito E, et al., 2015)

Tools and Technologies in Protein Crystallography

X-ray Sources

There are two main types of X-ray sources used in protein crystallography:

- Laboratory X-ray Sources: These are compact and easy to use but have lower intensity than synchrotron radiation.

- Synchrotron Radiation: Produced by large particle accelerators, synchrotron radiation provides high-intensity X-rays and is ideal for collecting high-quality diffraction data.

Detectors and Data Analysis Software

The X-ray diffraction data is collected by specialized detectors, such as CCD Detectors and Pixel Detectors. These detectors capture high-resolution data essential for structure determination. Data analysis is often carried out using specialized software, such as PHENIX, CCP4, and Refmac. These programs help scientists process diffraction data, build models, and refine structures.

Challenges and Future of Protein Crystallography

Current Challenges

Despite its power, protein crystallography faces several challenges:

- Crystallization Difficulties: Many proteins are difficult to crystallize, and even small impurities can hinder the process.

- Data Interpretation and Validation: Processing diffraction data and interpreting the electron density map is complex and requires careful validation.

Emerging Technologies

- Serial Crystallography: A technique that allows for the analysis of microcrystals, bypassing the need for large, single crystals.

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM): While not a replacement for crystallography, cryo-EM is becoming an important complementary technique, especially for proteins that are difficult to crystallize.

Future Prospects

The future of protein crystallography lies in integrating it with other techniques, such as cryo-EM, to provide a more comprehensive view of protein structures. Additionally, advances in automation and high-throughput methods may make the process faster and more accessible.

In conclusion, protein crystallography remains a cornerstone technique in structural biology, providing detailed insights into protein structures and their functions. From drug design to biotechnology, its applications have revolutionized fields like disease research, targeted therapies, and enzyme engineering. Despite challenges like crystallization difficulties, advancements in technology continue to expand its reach, offering new possibilities in medicine and industry. As the field evolves, the integration of complementary methods like cryo-EM promises to unlock even more complex protein structures.

At Creative Biostructure, we provide comprehensive protein x-ray crystallography services, offering one-stop solutions from protein purification and crystallization to data analysis and structure determination. However, if you only need support with a specific step, we are also happy to assist with individual services tailored to your needs. Contact us to discuss how our expert team can accelerate your research and development, no matter where you are in the process!

References

- Smyth M S, Martin J H J. X Ray crystallography. Molecular Pathology. 2000, 53(1): 8.

- Miyazaki K, Takenouchi M, Kondo H, et al. Thermal stabilization of Bacillus subtilis family-11 xylanase by directed evolution. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006, 281(15): 10236-10242.

- Ilari A, Savino C. Protein structure determination by x-ray crystallography. Bioinformatics: Data, Sequence Analysis and Evolution, 2008: 63-87.

- Mileni M, Garfunkle J, DeMartino J K, et al. Binding and inactivation mechanism of a humanized fatty acid amide hydrolase by α-ketoheterocycle inhibitors revealed from cocrystal structures. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009, 131(30): 10497-10506.

- Boutet S, Lomb L, Williams G J, et al. High-resolution protein structure determination by serial femtosecond crystallography. Science. 2012, 337(6092): 362-364.

- Apostol M I, Perry K, Surewicz W K. Crystal structure of a human prion protein fragment reveals a motif for oligomer formation. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2013, 135(28): 10202-10205.

- Akey D L, Brown W C, Dutta S, et al. Flavivirus NS1 crystal structures reveal a surface for membrane association and regions of interaction with the immune system. Science. 2014, 343(6173): 881.

- Malito E, Carfi A, Bottomley M J. Protein crystallography in vaccine research and development. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2015, 16(6): 13106-13140.

- Bassetto M, Massarotti A, Coluccia A, et al. Structural biology in antiviral drug discovery. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2016, 30: 116-130.

- Hutchison C D M, Cordon-Preciado V, Morgan R M L, et al. X-ray free electron laser determination of crystal structures of dark and light states of a reversibly photoswitching fluorescent protein at room temperature. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017, 18(9): 1918.

- Schmidt M. Time-resolved macromolecular crystallography at pulsed X-ray sources. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019, 20(6): 1401.

- Gawas U B, Mandrekar V K, Majik M S. Structural analysis of proteins using X-ray diffraction technique. Advances in biological science research. Academic Press, 2019: 69-84.

- Maveyraud L, Mourey L. Protein X-ray crystallography and drug discovery. Molecules. 2020, 25(5): 1030.

- Martin-Garcia J M. Protein dynamics and time resolved protein crystallography at synchrotron radiation sources: Past, present and future. Crystals. 2021, 11(5): 521.

- Liu Y, Liu Z, Guo Z, et al. Enhancement of the degradation capacity of IsPETase for PET plastic degradation by protein engineering. Science of The Total Environment. 2022, 834: 154947.

- Hatton C E, Mehrabi P. Exploring the dynamics of allostery through multi-dimensional crystallography. Biophysical Reviews. 2024, 16(5): 563-570.