Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) is a powerful imaging technique used to visualize and analyze surfaces at the nanometer and even atomic scale. Unlike optical and electron microscopy, AFM does not rely on lenses or electron beams, but instead uses a physical probe to scan the surface of a sample, making it an essential tool for nanoscale structural investigations. Widely used in structural biology, materials science and nanotechnology, AFM offers unique advantages for high-resolution imaging and analysis of molecular interactions.

Creative Biostructure offers comprehensive AFM services covering various fields including biology, materials science, and thin film technology.

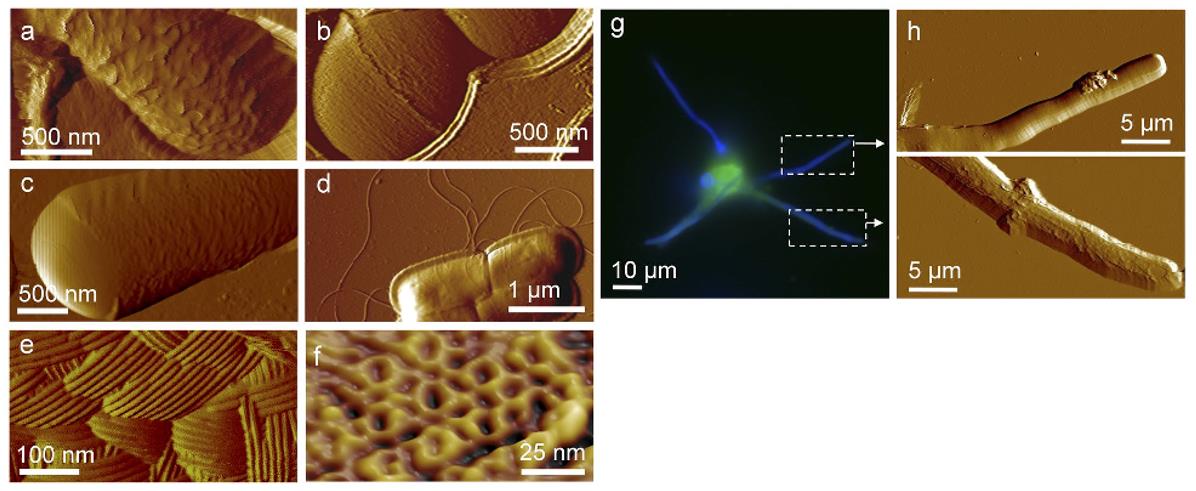

Figure 1. An illustration of the tip of an atomic force microscopy (AFM) and protein structures.

Figure 1. An illustration of the tip of an atomic force microscopy (AFM) and protein structures.

Principle and Equipment of AFM

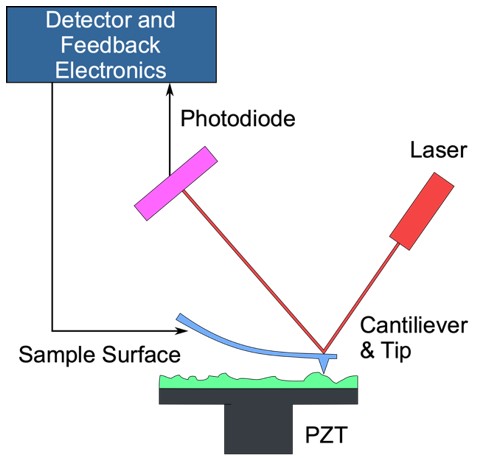

AFM operates on the principle of detecting and measuring forces between a sharp probe and the surface of a sample. These forces, which include Van der Waals interactions, electrostatic forces, and mechanical forces, are fundamental at the nanoscale and are key to AFM's ability to map surfaces with extreme precision. The AFM system consists of three critical components that work together to generate detailed topographic images:

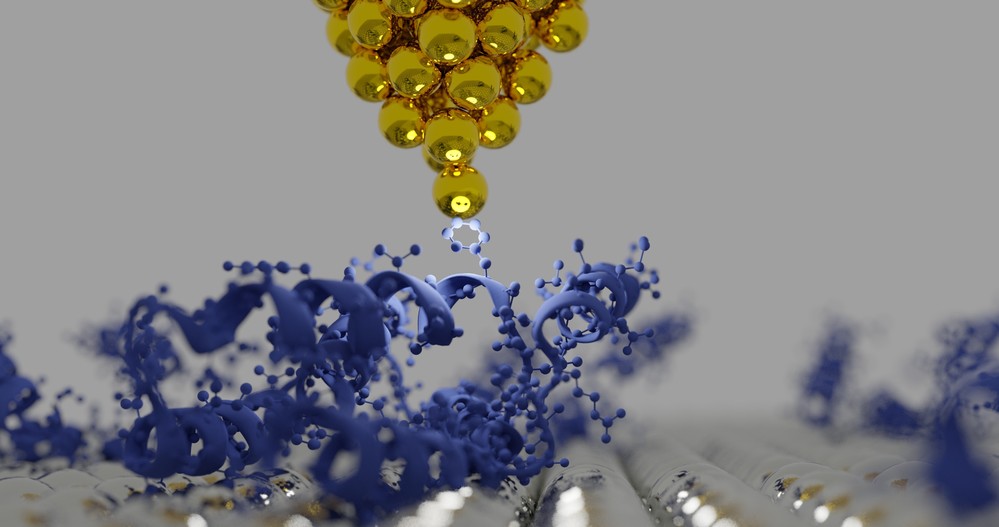

- Cantilever and Probe: At the heart of AFM is a cantilever, a tiny, flexible beam with a sharp tip at the end. This tip, typically made of materials such as silicon or silicon nitride, interacts with the surface of the sample. The radius of the tip is often only a few nanometers, allowing it to detect surface features with nanometer resolution. The cantilever flexes in response to the forces it encounters as it scans the sample, allowing the AFM to collect precise data on surface properties.

- Piezoelectric Scanner: The piezoelectric scanner plays a critical role in controlling the movement of the probe. This component can move the probe across the surface with sub-nanometer precision, ensuring that it accurately follows the contours of the sample. The high resolution of the piezoelectric scanner is key to AFM's ability to produce detailed surface maps at the atomic scale.

- Detection System: The AFM's detection system uses a laser beam that is reflected off the back of the cantilever. A photodetector captures the reflection and measures the deflection, or oscillation, of the cantilever as it moves across the surface. These deflections are directly related to the forces between the probe and the surface, allowing the system to generate high-resolution topographic maps of the sample surface.

As the tip approaches and moves along the sample surface, interactions between the probe and the material cause measurable deflections in the cantilever. These deflections are then converted into a topographic map that provides detailed insight into the surface structure and mechanical properties of the sample. This ability to visualize and measure nanoscale surface features makes AFM a powerful tool in materials science, biology, and nanotechnology.

Figure. 2. An AFM generates images by scanning a small cantilever over the surface of a sample. The sharp tip on the end of the cantilever contacts the surface, bending the cantilever and changing the amount of laser light reflected into the photodiode. The height of the cantilever is then adjusted to restore the response signal, resulting in the measured cantilever height tracing the surface.

Figure. 2. An AFM generates images by scanning a small cantilever over the surface of a sample. The sharp tip on the end of the cantilever contacts the surface, bending the cantilever and changing the amount of laser light reflected into the photodiode. The height of the cantilever is then adjusted to restore the response signal, resulting in the measured cantilever height tracing the surface.

Modes of Operation

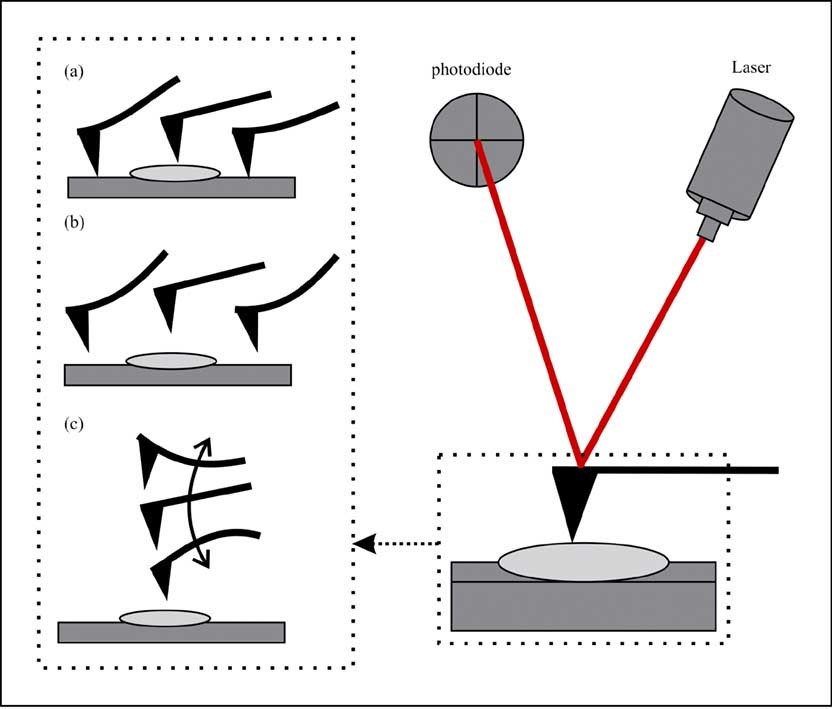

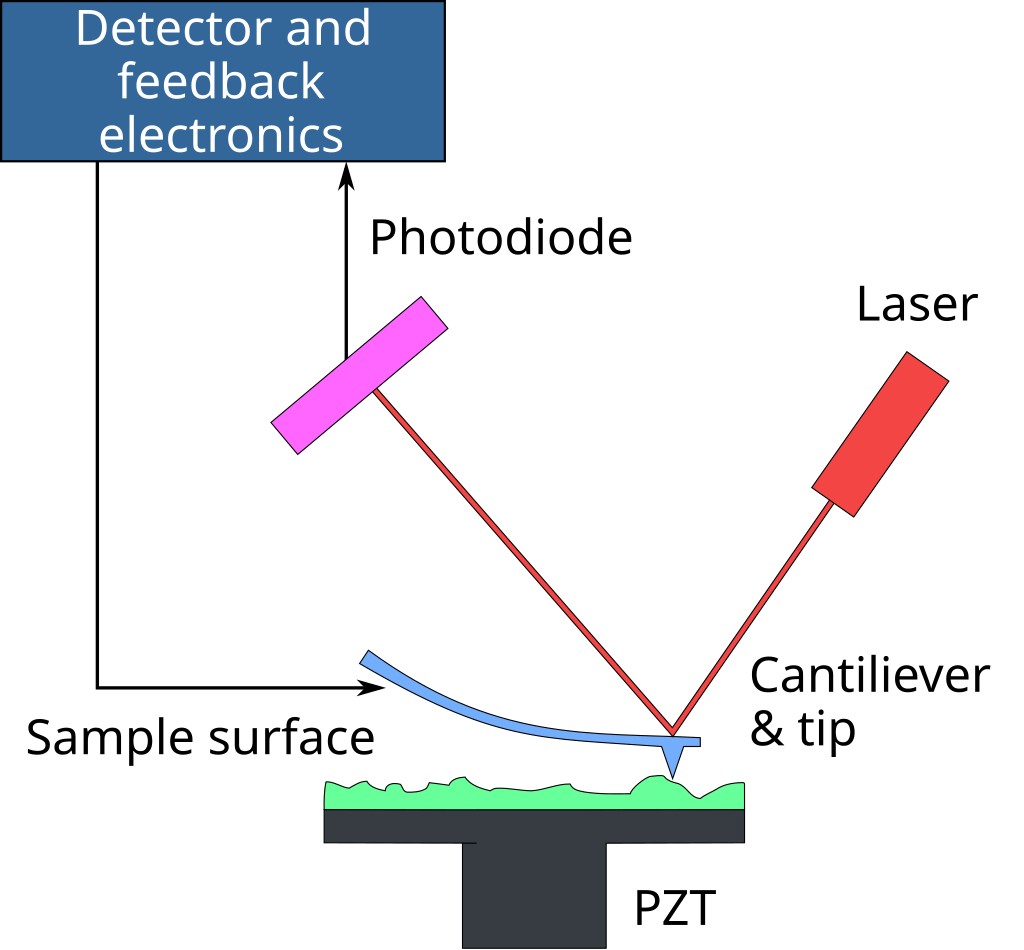

AFM can be operated in different modes depending on the nature of the sample and the information required:

- Contact Mode: The probe remains in constant contact with the sample surface and repulsive forces are measured. This mode provides high resolution images but can damage soft biological samples.

- Tapping Mode (Intermittent Contact Mode): The cantilever oscillates, and the tip briefly contacts the surface during each oscillation cycle. This reduces damage to delicate structures and is widely used for biological samples.

- Non-Contact Mode: The probe floats above the sample and detects attractive forces without physical contact, preserving sample integrity while sacrificing some resolution.

Figure. 3. Operating modes of the AFM. (a) Contact mode. (b) Tapping mode. (c) Non-contact mode. (Rana et al., 2017)

Figure. 3. Operating modes of the AFM. (a) Contact mode. (b) Tapping mode. (c) Non-contact mode. (Rana et al., 2017)

Equipment of AFM

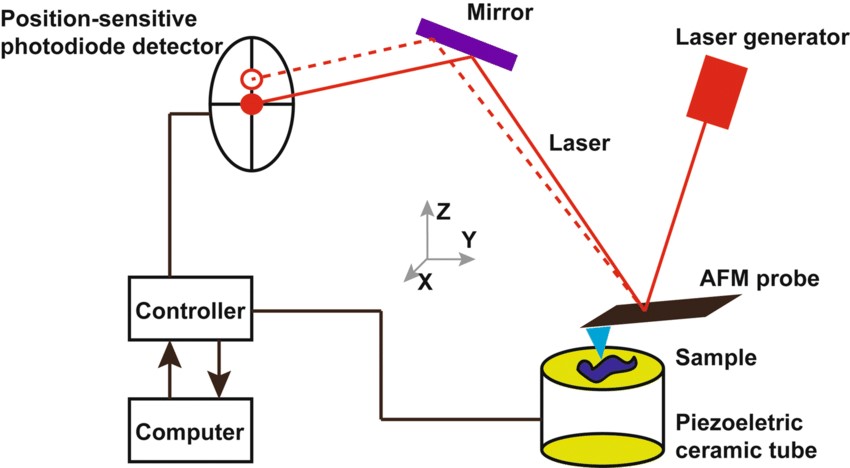

The basic components of an AFM setup include:

- Cantilever and Tip: The tip geometry determines resolution and interaction forces.

- Laser and Photodetector: A laser is reflected from the cantilever and detected by a photodiode to measure displacement.

- Piezoelectric Scanner: Moves the sample in nanometer steps for precise scanning.

- Feedback Control System: Maintains the probe at an optimal distance from the sample by adjusting the tip height based on the deflection signal.

- Vibration Isolation System: Minimizes external noise and vibration that can interfere with AFM measurements.

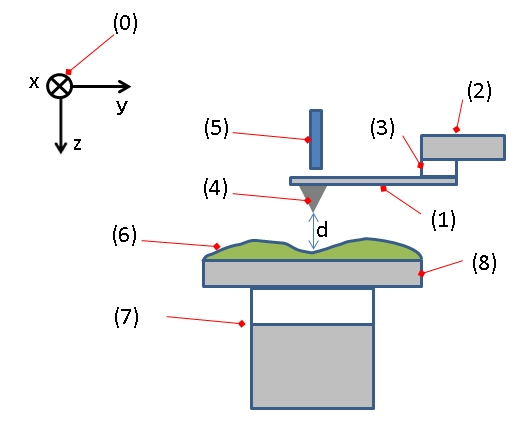

Figure. 4: Typical configuration of an AFM. (1): Cantilever, (2): Support for cantilever, (3): Piezoelectric element (to oscillate cantilever at its eigen frequency), (4): Tip (Fixed to open end of a cantilever, acts as the probe), (5): Detector of deflection and motion of the cantilever, (6): Sample to be measured by AFM, (7): xyz drive, (moves sample (6) and stage (8) in x, y, and z directions with respect to a tip apex (4)), and (8): Stage.

Figure. 4: Typical configuration of an AFM. (1): Cantilever, (2): Support for cantilever, (3): Piezoelectric element (to oscillate cantilever at its eigen frequency), (4): Tip (Fixed to open end of a cantilever, acts as the probe), (5): Detector of deflection and motion of the cantilever, (6): Sample to be measured by AFM, (7): xyz drive, (moves sample (6) and stage (8) in x, y, and z directions with respect to a tip apex (4)), and (8): Stage.

Resolution of an AFM

The resolution of an AFM varies depending on the imaging mode and environmental conditions. In general, AFM achieves:

- Lateral (XY) Resolution: ~1–10 nm

- Vertical (Z) Resolution: ~0.1 nm (sub-nanometer level)

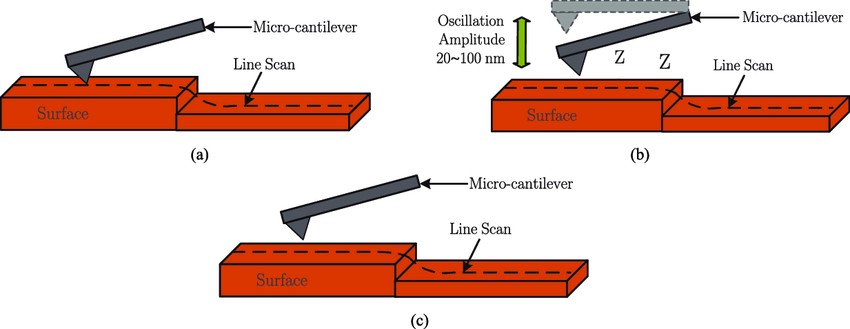

AFM's vertical resolution is significantly higher than its lateral resolution, allowing it to detect atomic-scale variations in surface height. Resolution can also be increased by using specialized probes and imaging techniques such as high-speed AFM or phase imaging.

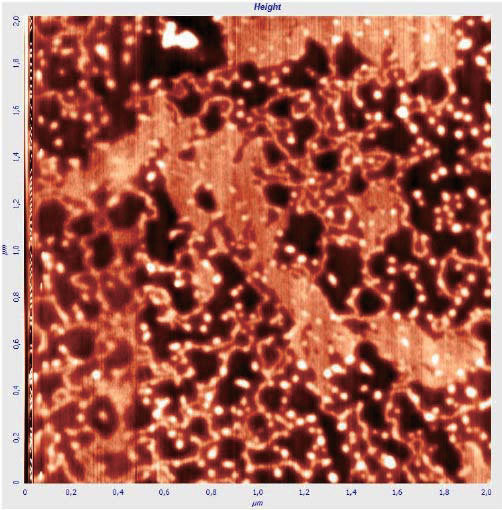

Figure. 5: High-resolution atomic force microscopy of DNA molecules on a membrane applied by drying without blowing (in the figure, the DNA is mixed with impurities). Colors in topography images represent the height variation h = 10 nm. (Orlov et al., 2018)

Figure. 5: High-resolution atomic force microscopy of DNA molecules on a membrane applied by drying without blowing (in the figure, the DNA is mixed with impurities). Colors in topography images represent the height variation h = 10 nm. (Orlov et al., 2018)

Applications of AFM

Applications of AFM in Biology

| Imaging of Biomolecules and Cellular Structures | AFM enables the visualization of DNA, proteins, lipid bilayers, and cellular components with nanometer resolution. It is particularly useful for studying the structural organization of biological membranes and protein aggregates, which are difficult to analyze using other techniques. |

| Protein Unfolding and Molecular Interactions | AFM can be used to probe the mechanical properties of individual proteins by pulling on them and measuring unfolding forces. This has been instrumental in studying protein dynamics, ligand-receptor interactions, and protein-DNA interactions. |

| Live-Cell Imaging | Unlike electron microscopy, which requires fixed and stained samples, AFM can analyze living cells and capture dynamic cellular processes such as adhesion, division, and motility. |

| High-Resolution Mapping of Cell Surface Properties | AFM is used to measure cell stiffness, elasticity, and adhesion forces, which are critical in understanding cellular mechanics and disease pathology, including cancer progression and microbial biofilms. |

| Nanomanipulation and Drug Delivery Studies | By functionalizing the AFM tip, researchers can manipulate biomolecules and study how drugs interact with cellular membranes, paving the way for targeted drug delivery research. |

Applications of AFM in Materials Science

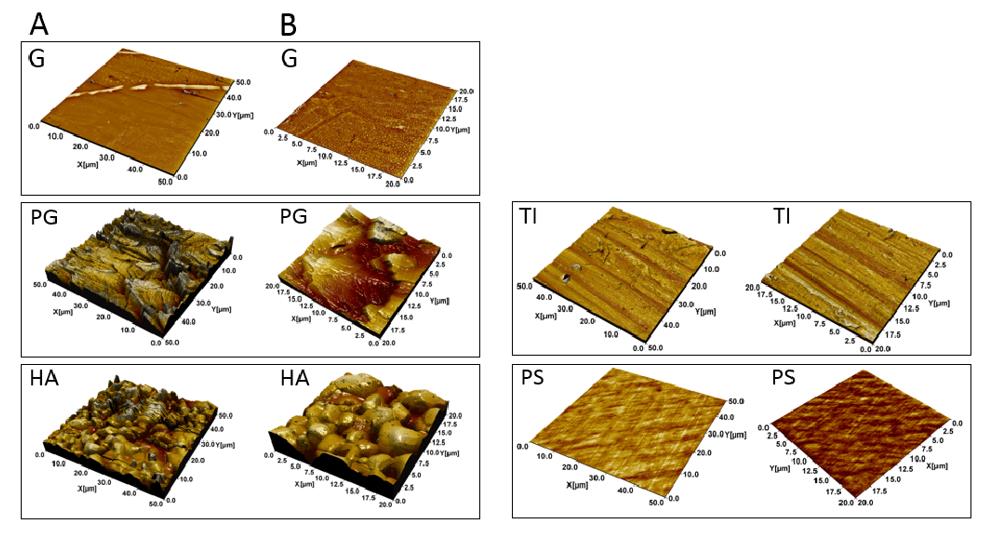

| Surface Topography and Roughness Analysis | AFM provides detailed 3D images of material surfaces, aiding in the study of nanostructured materials and coatings. |

| Nanomechanical Property Characterization | AFM measures hardness, elasticity, and adhesion forces at the nanoscale, supporting the development of novel materials for industrial applications. |

| Polymer Characterization | AFM helps study polymer morphology, phase separation, and thermal effects on material structure. |

| Corrosion and Wear Studies | AFM studies degradation patterns and mechanical wear in metals and coatings to improve material durability. |

| Nanomanipulation and Lithography | AFM can modify surfaces at the nanoscale, enabling the fabrication of nanostructures and functional devices. |

Applications of AFM in Thin Film Technology

| Thickness and Uniformity Analysis | AFM accurately measures film thickness and detects defects to ensure the consistency of coatings used in semiconductors and biomedical devices. |

| Grain Size and Morphology Characterization | The technique provides insight into the crystallinity, grain boundaries, and texture of thin films to optimize their properties for specific applications. |

| Electrical and Conductive Mapping | Conductive AFM (C-AFM) evaluates the electrical properties of thin films, essential for the development of nanoelectronic devices and photovoltaic materials. |

| Surface Adhesion and Friction Studies | AFM quantifies adhesion and tribological properties of coatings, improving wear resistance in industrial applications. |

| Film Growth Monitoring | AFM assists in the study of deposition techniques such as chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and atomic layer deposition (ALD) to refine manufacturing processes. |

Applications of AFM in Physical Science

| Nanotribology and Surface Forces | AFM measures friction, adhesion and wear at the atomic level to improve lubrication and material performance. |

| Electromagnetic and Conductive Studies | Variants of AFM, such as Magnetic Force Microscopy (MFM) and Electrostatic Force Microscopy (EFM), analyze magnetic domains and surface charge distributions. |

| Quantum Dot and Nanoparticle Analysis | AFM characterizes nanomaterials used in quantum computing, nanoelectronics, and plasmonic devices. |

| Low-Temperature and Ultra-High Vacuum Studies | AFM operates under extreme conditions to study atomic-scale interactions that are critical to condensed matter physics and superconductivity research. |

| Scanning Probe Lithography | AFM-based nanolithography enables the fabrication of nanoscale circuits and quantum devices, advancing semiconductor technology. |

Case Study

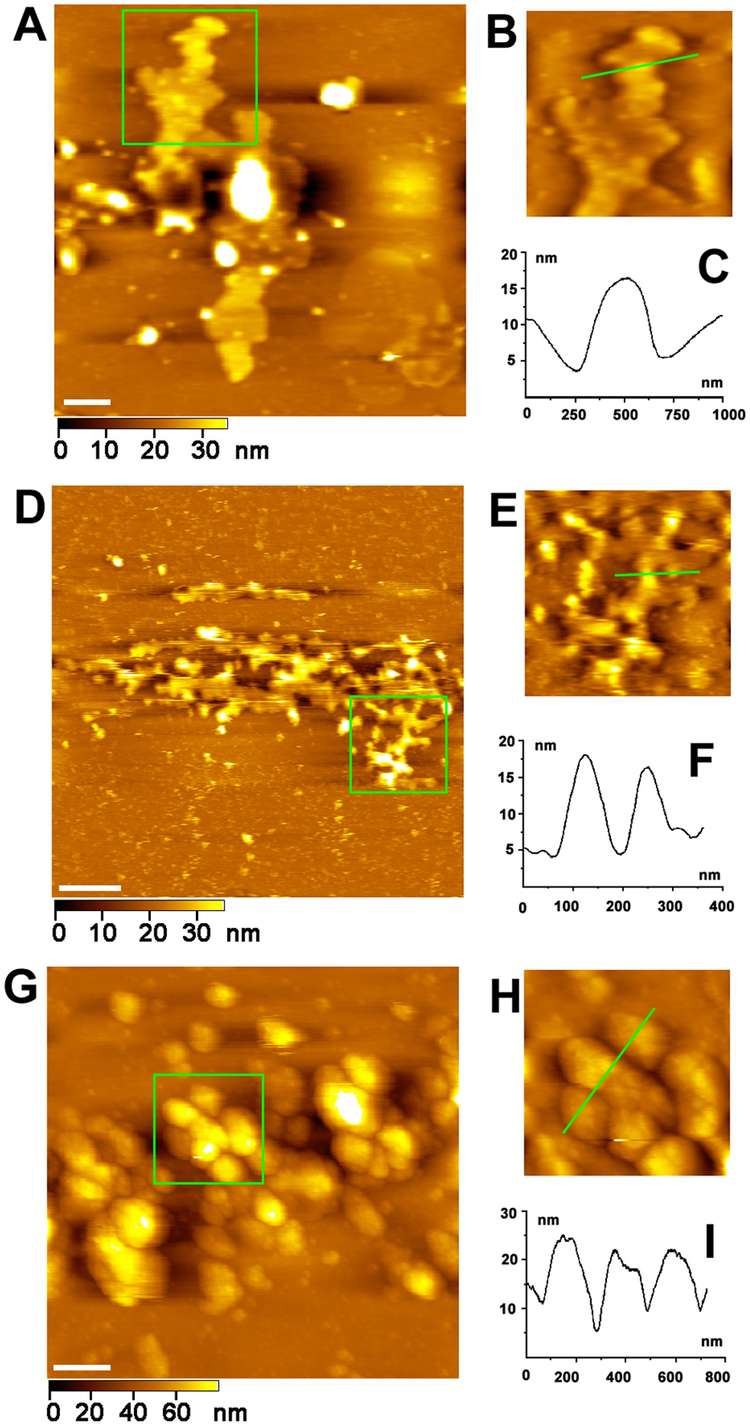

Case 1: The Asymmetrical Structure of Golgi Apparatus Membranes Revealed by in situ Atomic Force Microscope

In this study, Xu's group directly visualized the structure of the Golgi apparatus, including the Golgi stack, cisternal arrangement, and associated tubules and vesicles, using high-resolution atomic force microscopy (AFM). By imaging both sides of the Golgi membrane, they found that the outer leaflet of the membrane is relatively smooth, while the inner leaflet is rough and densely populated with proteins. Through treatment with methyl-β-cyclodextrin and Triton X-100, the researchers identified lipid rafts within the Golgi membrane, most of which ranged in size from 20 nm to 200 nm and had irregular shapes. These findings provide valuable insights into the structure-function relationship of the Golgi complex and represent a step toward visualizing the endomembrane system in mammalian cells at the molecular level.

Figure 6. AFM images of Golgi apparatus. (A) AFM image of a stack of membranous cisternae. Scale bar is 1 µm. (B) Magnification of the green square area in (A). (C) Cross-section analysis along the green line drawn in (B). (D) AFM image of tubule network of Golgi apparatus. Scale bar is 1 µm. (E) Magnification of the green square area in (D). (F) Cross-section analysis along the green line drawn in (E). (G) AFM image of vesicles of Golgi apparatus. Scale bar is 1 µm. (H) Magnification of the green square area in (G). (I) Cross-section analysis along the green line drawn in (H). (Xu et al., 2013)

Figure 6. AFM images of Golgi apparatus. (A) AFM image of a stack of membranous cisternae. Scale bar is 1 µm. (B) Magnification of the green square area in (A). (C) Cross-section analysis along the green line drawn in (B). (D) AFM image of tubule network of Golgi apparatus. Scale bar is 1 µm. (E) Magnification of the green square area in (D). (F) Cross-section analysis along the green line drawn in (E). (G) AFM image of vesicles of Golgi apparatus. Scale bar is 1 µm. (H) Magnification of the green square area in (G). (I) Cross-section analysis along the green line drawn in (H). (Xu et al., 2013)

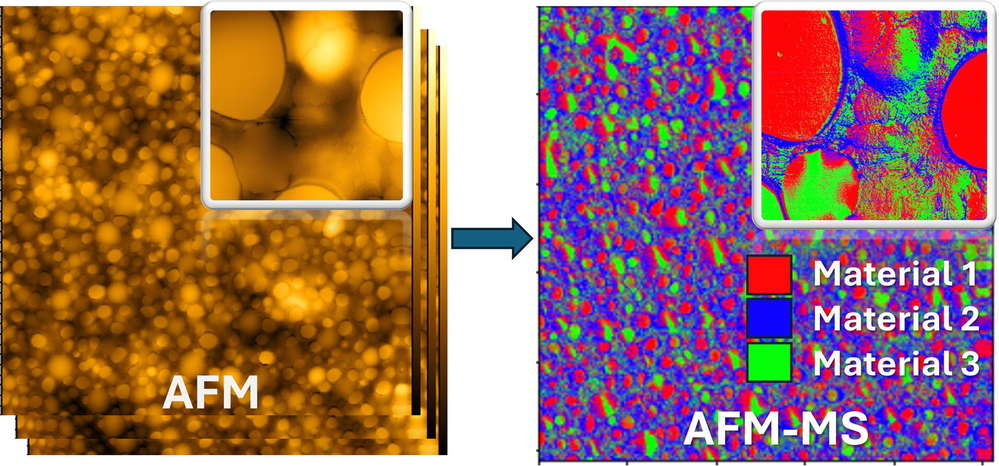

Case 2: Mechanical Spectroscopy of Materials Using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM-MS)

In this study, the researchers introduce a novel mechano-spectroscopic atomic force microscopy (AFM-MS) technique that addresses the limitations of current spectroscopic methods by integrating the high-resolution imaging capabilities of AFM with machine learning (ML) classification. AFM-MS uses AFM in sub-resonance tapping mode, which allows the collection of multiple physical and mechanical property maps of a sample with sub-nanometer lateral resolution, ensuring highly reproducible results. By comparing these properties to a database of known materials, the technique can use ML algorithms to determine the location of different materials at each image pixel. They demonstrate the application of AFM-MS to different material mixtures, achieving an unprecedented lateral spectroscopic resolution of 1.6 nm. This powerful approach paves the way for advanced nanoscale materials analysis, enabling material identification and correlation of nanostructures with macroscopic material properties.

Figure 7. Mechanical spectroscopy of materials using atomic force microscopy (AFM-MS). (Petrov et al., 2024)

Figure 7. Mechanical spectroscopy of materials using atomic force microscopy (AFM-MS). (Petrov et al., 2024)

Comparison of AFM with Other Microscopy Techniques

AFM is often compared to other advanced microscopy techniques used in structural biology, such as Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), and Confocal Microscopy. Below is a comparative analysis:

| Feature | Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Confocal Microscopy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | ~1 nm | ~1-10 nm | <1 nm | ~200 nm |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal, no staining required | Requires conductive coating | Requires ultrathin sectioning | Requires fluorescent labeling |

| Imaging Environment | Air, liquid, vacuum | Vacuum | Vacuum | Air or liquid |

| Live Sample Imaging | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Depth Information | 3D topography | 2D image | 2D image | Optical sectioning for 3D reconstruction |

| Structural Biology Applications | Protein dynamics, cell mechanics | Surface morphology of cells and biomaterials | Ultra-high resolution of macromolecular structures | Cellular imaging and localization of biomolecules |

Advantages and Limitations of AFM

Advantages of AFM Over Other Techniques

- Minimal Sample Preparation: Unlike electron microscopy, which requires extensive sample processing, AFM can be performed in near-physiological conditions.

- 3D Imaging: AFM provides high-resolution three-dimensional topographical images, whereas SEM and TEM offer only two-dimensional images.

- Live-Cell Imaging: AFM is one of the few techniques capable of imaging live cells without staining or fixation.

Limitations of AFM Compared to Other Techniques

- Slower Imaging Speed: AFM scans point by point, making it significantly slower than optical or electron microscopy.

- Limited Field of View: The scan size is typically a few micrometers, making it unsuitable for imaging large tissue sections.

- Tip Convolution Effects: The shape of the AFM tip can influence the resolution and accuracy of structural details.

In summary, atomic force microscopy is an extremely versatile and powerful tool in structural biology, providing nanoscale imaging and mechanical characterization of biomolecules, cells, and surfaces. Its ability to operate under near-physiological conditions makes it indispensable for the study of dynamic biological processes. Compared to other microscopy techniques, AFM offers unique advantages such as 3D imaging, minimal sample preparation, and live cell imaging, although it has limitations in imaging speed and field of view.

Creative Biostructure offers you highly accurate AFM measurements such as surface topography, dopant distribution, magnetic domain features, and various other sample properties to give you the information you need to do great work. Please feel free to contact us for more information or a detailed quote.

References

- Orlov AP, Smolovich AM, Barinov NA, et al. Assembling nanostructures from DNA using a composite nanotweezers with a shape memory effect. In: 2018 IEEE International Conference on Manipulation, Manufacturing and Measurement on the Nanoscale (3M-NANO). IEEE; 2018:118-121. doi:10.1109/3M-NANO.2018.8552165

- Petrov M, Canena D, Kulachenkov N, et al. Mechanical spectroscopy of materials using atomic force microscopy (AFM-MS). Materials Today. 2024;80:218-225. doi:10.1016/j.mattod.2024.08.021

- Rana MS, Pota HR, Petersen IR. Improvement in the imaging performance of atomic force microscopy: a survey. IEEE Trans Automat Sci Eng. 2017;14(2):1265-1285. doi:10.1109/TASE.2016.2538319

- Xu H, Su W, Cai M, Jiang J, Zeng X, Wang H. The asymmetrical structure of Golgi apparatus membranes revealed by in situ atomic force microscope. Dalal Y, ed. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e61596. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0061596