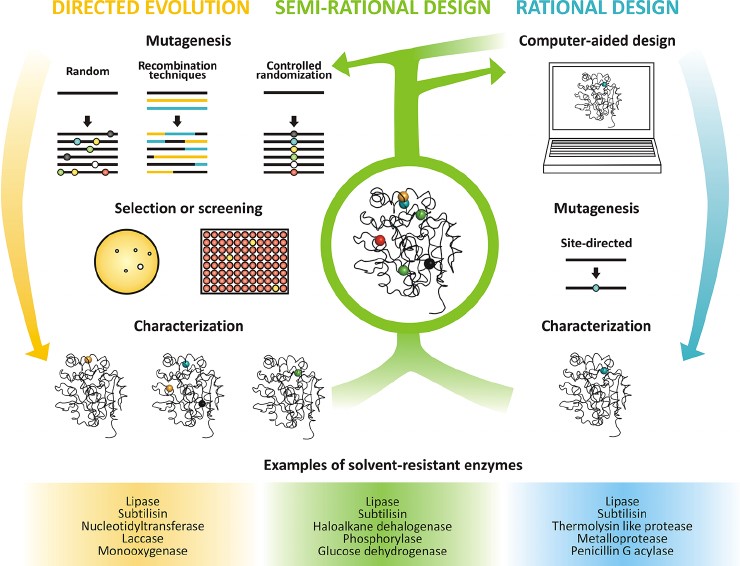

Protein synthesis is a fundamental biological process by which cells make proteins based on genetic instructions. It involves two primary steps: transcription and translation. While the core principles of protein synthesis are conserved across all domains of life, there are significant differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems. These differences arise from variations in cellular structures, regulatory mechanisms, and the efficiency of translation.

In this article, Creative Biostructure provides a detailed comparative analysis of protein synthesis in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, highlighting key differences in transcription, translation, ribosomal structure, and post-translational modifications. With proven expertise, we offer advanced protein production and engineering services in prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems, particularly in membrane proteins and custom engineering.

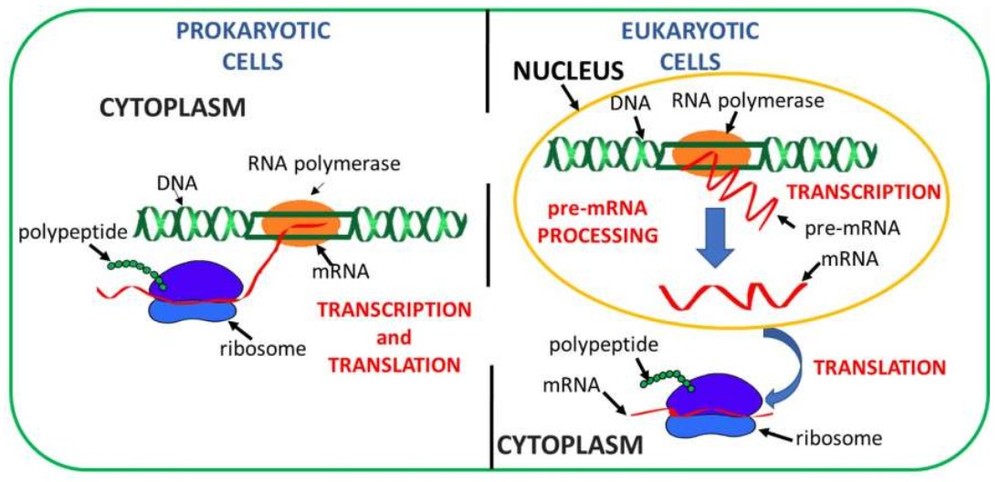

Figure 1. Steps involved in protein synthesis in prokaryotic (left) and eukaryotic cells (right). (Campofelice et al., 2019)

Figure 1. Steps involved in protein synthesis in prokaryotic (left) and eukaryotic cells (right). (Campofelice et al., 2019)

Overview of Protein Synthesis

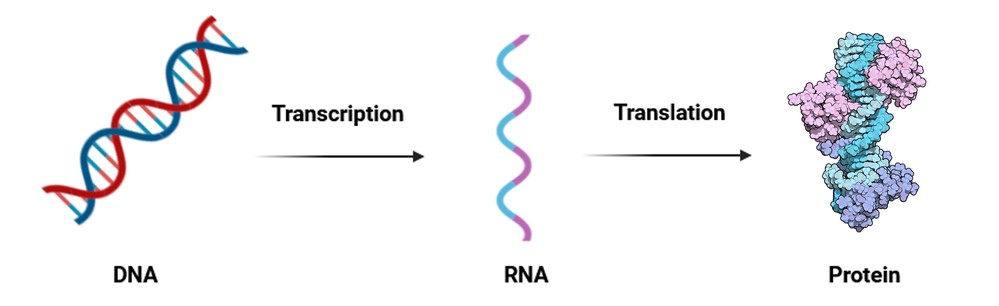

Protein synthesis is a fundamental biological process by which cells generate new proteins necessary for cellular function, growth, and maintenance. It is a highly coordinated mechanism involving multiple molecular components, including DNA, RNA, ribosomes, and enzymes. The process is divided into two main stages:

- Transcription: This stage involves the conversion of genetic information stored in DNA into messenger RNA (mRNA). The mRNA serves as a template that carries the genetic code from the nucleus (in eukaryotic cells) or the cytoplasm (in prokaryotic cells) to the ribosomes for translation.

- Translation: This stage involves the decoding of the mRNA sequence into a specific polypeptide chain. Ribosomes facilitate this process by ensuring that the correct amino acids are incorporated into the growing protein.

Both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells follow this basic process, but they differ significantly in their mechanisms and efficiency due to structural and regulatory differences.

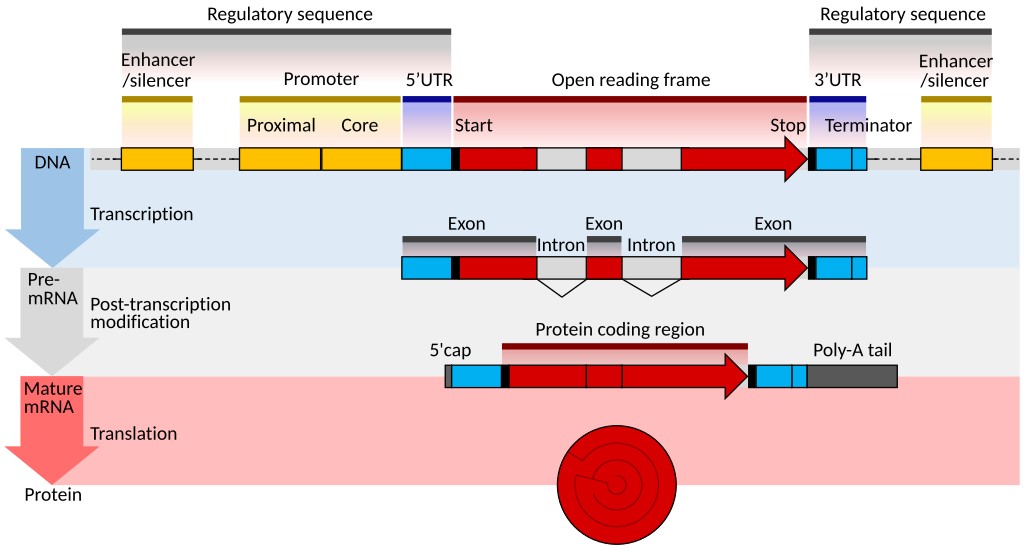

Figure 2. Two main stages of protein synthesis: transcription and translation.

Figure 2. Two main stages of protein synthesis: transcription and translation.

Differences in Transcription

Location of Transcription

One of the most notable differences between prokaryotes and eukaryotes is the cellular location where transcription occurs.

- Prokaryotes: Transcription occurs in the cytoplasm because prokaryotic cells lack a membrane-bound nucleus. Consequently, transcription and translation are often coupled, meaning translation can begin before transcription is complete.

- Eukaryotes: Transcription takes place in the nucleus, where DNA is enclosed by a nuclear membrane. This spatial separation ensures that mRNA undergoes extensive modifications before being transported to the cytoplasm for translation.

RNA Polymerases

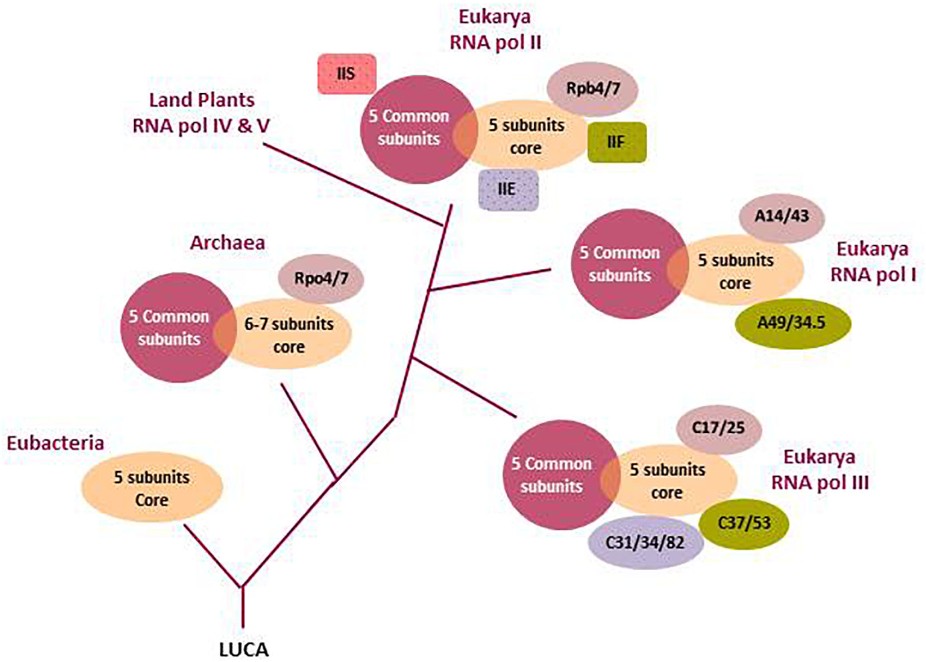

The enzymes responsible for transcription also vary between prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

- Prokaryotes: Use a single RNA polymerase enzyme to synthesize all types of RNA, including mRNA, ribosomal RNA (rRNA), and transfer RNA (tRNA).

- Eukaryotes: Have three different RNA polymerases and the presence of multiple polymerases in eukaryotes allows for more specialized and complex regulation of gene expression.

- RNA Polymerase I produces rRNA, which is essential for ribosome assembly.

- RNA Polymerase II generates mRNA, which requires precise regulation due to its role in protein-coding genes.

- RNA Polymerase III synthesizes tRNA and small RNAs, crucial for translation. This division allows eukaryotes to finely tune gene expression, supporting complex cellular functions.

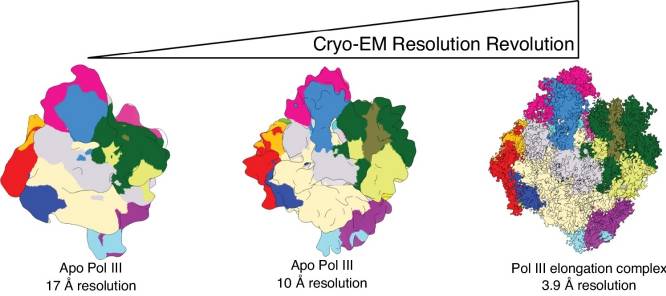

Figure 3. Evolutionary history and subunit organization of nuclear eukaryotic RNA polymerases. The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) of all organisms is assumed to have a multisubunit DNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Nowadays, all living beings have RNA pols with a core of five to seven subunits. After Eubacteria separation, the common ancestor of Archaea and Eukarya added additional peripheral subunits. Finally, after eukaryote emergence, the Archaea-derived nucleus started to develop specialized RNA polymerases. Specialized RNA pols I and III integrated some transcription factors as permanent subunits which, in RNA pol II, remain independent (TFIIS, TFIIF, TFIIE). RNA pol IV and V are not fully described. Only the branching after RNA pol I separation is indicated. See the main text for further descriptions. (Barba-Aliaga et al., 2021)

Figure 3. Evolutionary history and subunit organization of nuclear eukaryotic RNA polymerases. The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) of all organisms is assumed to have a multisubunit DNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Nowadays, all living beings have RNA pols with a core of five to seven subunits. After Eubacteria separation, the common ancestor of Archaea and Eukarya added additional peripheral subunits. Finally, after eukaryote emergence, the Archaea-derived nucleus started to develop specialized RNA polymerases. Specialized RNA pols I and III integrated some transcription factors as permanent subunits which, in RNA pol II, remain independent (TFIIS, TFIIF, TFIIE). RNA pol IV and V are not fully described. Only the branching after RNA pol I separation is indicated. See the main text for further descriptions. (Barba-Aliaga et al., 2021)

Transcription Initiation

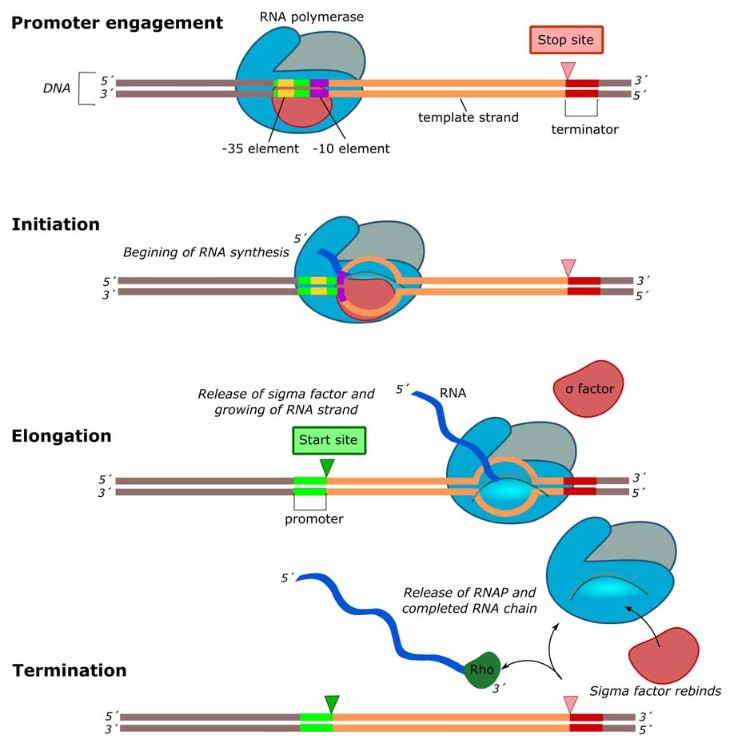

The initiation of transcription differs significantly between prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems.

- Prokaryotes: Transcription is initiated when RNA polymerase binds directly to a promoter sequence containing conserved regions such as the -10 (Pribnow box) and -35 sequences.

Figure 4. Graphic representation of the bacterial transcription process. Transcription begins with the recognition of the − 10 Schaller-Pribnow box (purple rectangle), and the − 35 element (yellow box) by the sigma factor (reddish oval) leading to the promoter (green rectangle) engagement. Transcription initiation requires formation of the transcription bubble, with RNA (dark blue wavy line) synthesis initiating at the start site (green triangle). Sigma factor falls off during RNA elongation, allowing the RNAP to continue copying the DNA (thick gray line) into RNA. Rho factor (dark green oval) moves along the forming RNA chain, following the RNAP complex until it reaches the terminator (thick red line). This completes transcription of the gene (thick orange line), Rho unwinds the DNA-RNA hybrid within the transcription bubble, and the RNAP, Rho, and newly formed RNA strand are released. (Abril et al., 2020)

Figure 4. Graphic representation of the bacterial transcription process. Transcription begins with the recognition of the − 10 Schaller-Pribnow box (purple rectangle), and the − 35 element (yellow box) by the sigma factor (reddish oval) leading to the promoter (green rectangle) engagement. Transcription initiation requires formation of the transcription bubble, with RNA (dark blue wavy line) synthesis initiating at the start site (green triangle). Sigma factor falls off during RNA elongation, allowing the RNAP to continue copying the DNA (thick gray line) into RNA. Rho factor (dark green oval) moves along the forming RNA chain, following the RNAP complex until it reaches the terminator (thick red line). This completes transcription of the gene (thick orange line), Rho unwinds the DNA-RNA hybrid within the transcription bubble, and the RNAP, Rho, and newly formed RNA strand are released. (Abril et al., 2020)

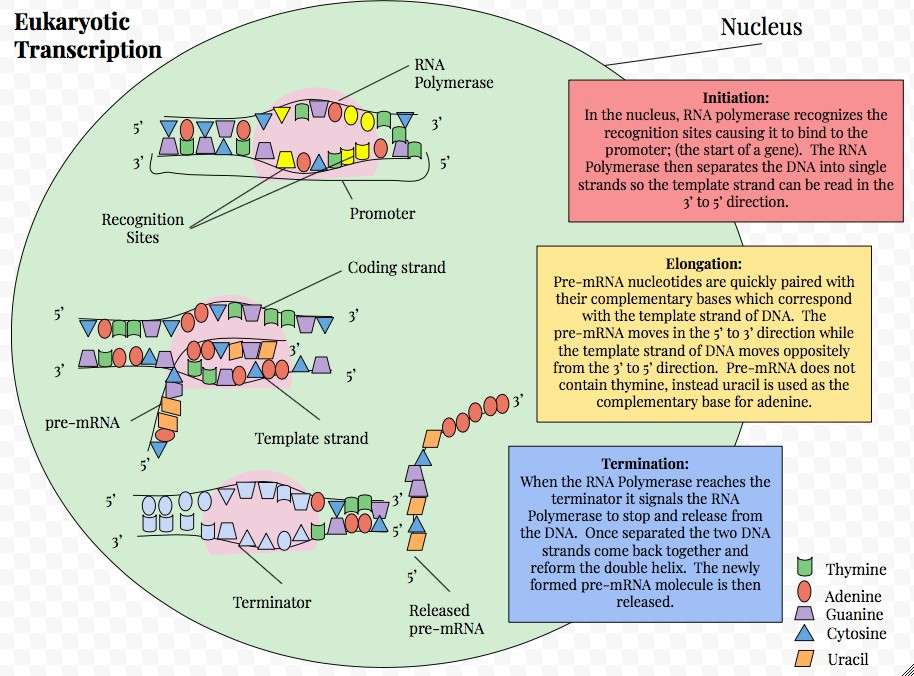

- Eukaryotes: Require additional transcription factors to help RNA polymerase bind to the promoter region. The promoter often contains a TATA box, typically located about 25 base pairs upstream of the transcription start site. These factors contribute to complex gene regulation, allowing tissue-specific and developmental control of gene expression. The need for transcription factors in eukaryotes allows for complex regulation of gene expression, including tissue-specific transcription.

Figure 5. Graphic representation of eukaryotic transcription.

Figure 5. Graphic representation of eukaryotic transcription.

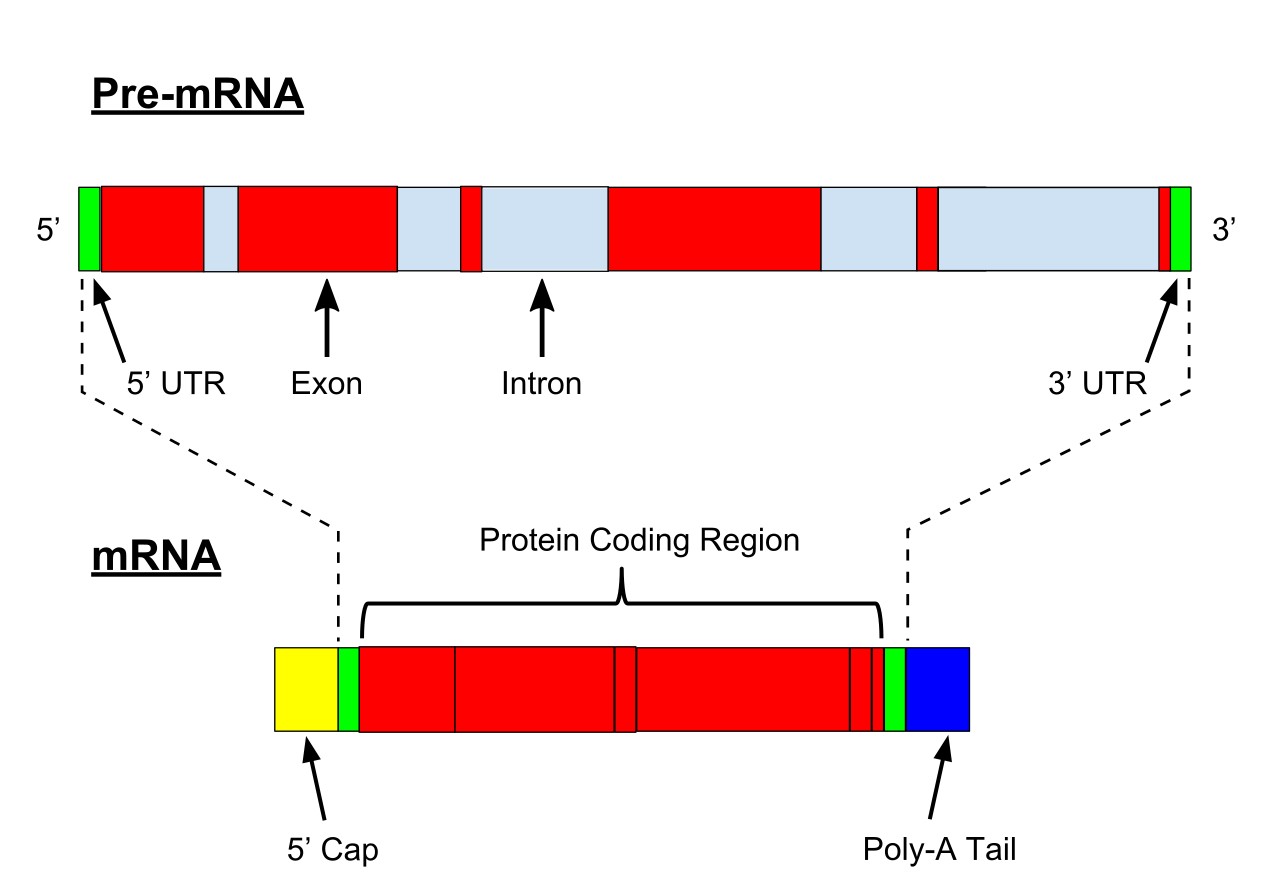

mRNA Processing

One of the most striking differences in transcription is the post-transcriptional modification of mRNA.

- Prokaryotes: Produce polycistronic mRNA, encoding multiple proteins from a single transcript (e.g., operons). This efficiency suits their unicellular lifestyle. Their mRNA is translated immediately without modification.

- Eukaryotes: Produce monocistronic mRNA, encoding a single protein per transcript. The mRNA undergoes extensive modifications, including:

- 5' Capping: A modified guanine nucleotide stabilizes the mRNA and facilitates ribosome binding.

- Splicing: Introns (non-coding regions) are removed and exons are added, allowing alternative splicing to diversify proteins from a single gene.

- 3' Polyadenylation: A poly A tail increases stability and nuclear export. These steps ensure mRNA longevity and fidelity, which are critical for complex organisms. These modifications ensure that eukaryotic mRNA is stable and properly translated in the cytoplasm.

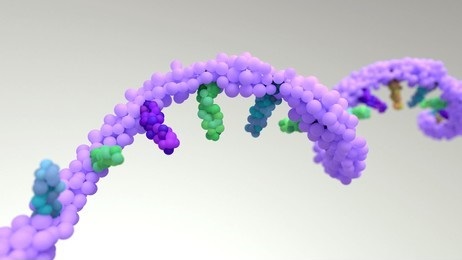

Figure 6. Pre-mRNA is the first form of RNA created through transcription in protein synthesis. The pre-mRNA lacks structures that the messenger RNA (mRNA) requires. First all introns have to be removed from the transcribed RNA through a process known as splicing. Before the RNA is ready for export, a Poly(A)tail is added to the 3' end of the RNA and a 5' cap is added to the 5' end.

Figure 6. Pre-mRNA is the first form of RNA created through transcription in protein synthesis. The pre-mRNA lacks structures that the messenger RNA (mRNA) requires. First all introns have to be removed from the transcribed RNA through a process known as splicing. Before the RNA is ready for export, a Poly(A)tail is added to the 3' end of the RNA and a 5' cap is added to the 5' end.

Differences in Translation

Location of Translation

Due to structural differences, translation occurs differently in prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

- Prokaryotes: Translation occurs in the cytoplasm, and it is coupled to transcription.

- Eukaryotes: Translation occurs in the cytoplasm (for cytosolic proteins) or at the rough endoplasmic reticulum (for secretory and membrane proteins). Separation from transcription allows for additional regulatory mechanisms.

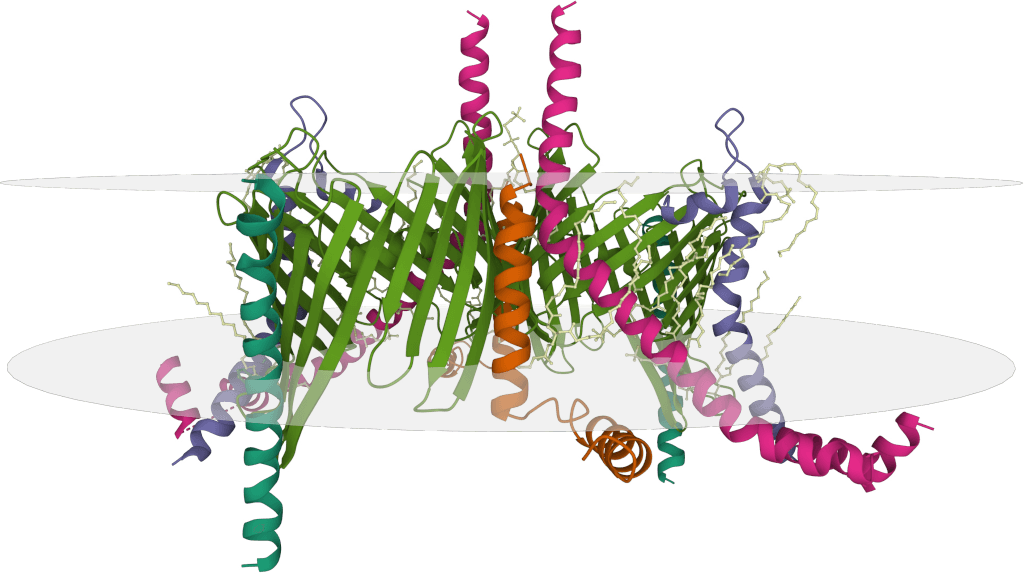

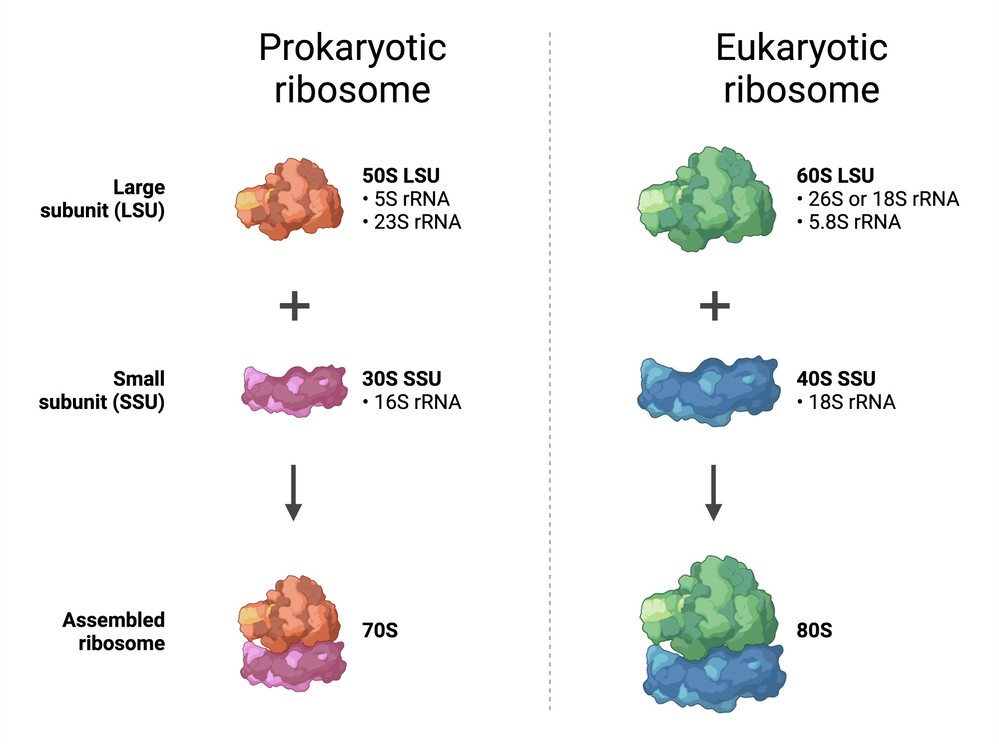

Ribosomal Structure

Ribosomes are the molecular machines responsible for protein synthesis, and their composition differs between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells.

- Prokaryotic ribosome: 70S ribosome, composed of 50S large subunit and 30S small subunit.

- Eukaryotic ribosome: 80S ribosome, composed of 60S large subunit and 40S small subunit. The larger eukaryotic ribosome allows for more complex interactions with translation factors and regulatory elements.

Figure 7. Structure of prokaryotic and eukaryotic ribosome. (Created with BioRender.com)

Figure 7. Structure of prokaryotic and eukaryotic ribosome. (Created with BioRender.com)

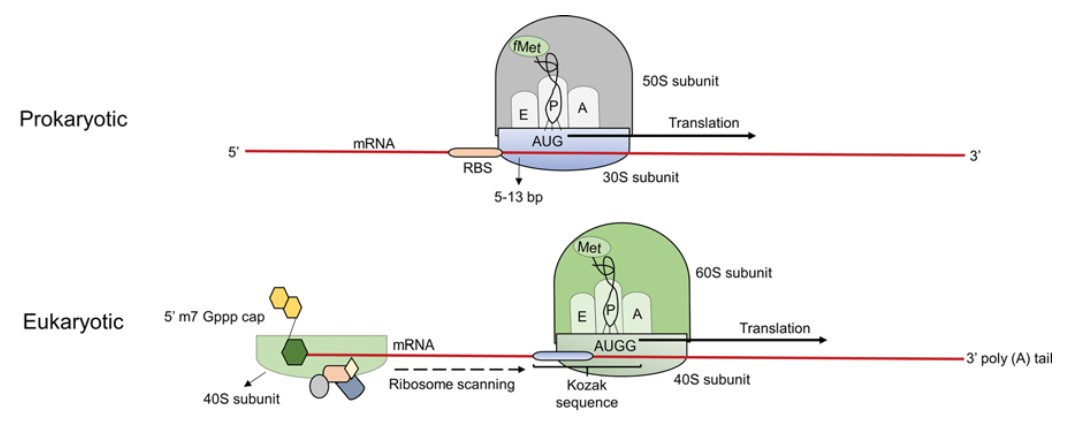

Initiation of Translation

Translation initiation is also significantly different in prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

- Prokaryotes: Initiation begins at the Shine-Dalgarno sequence, a ribosomal binding site located upstream of the start codon (AUG).

- Eukaryotes: The ribosome recognizes the 5' cap structure of the mRNA and scans until it finds the start codon. Eukaryotic translation initiation is more complex and involves several eukaryotic initiation factors (eIFs).

Figure 8. Schematic representation of initiation of translation in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. In prokaryotes, the small ribosome subunit binds to the ribosome-binding site (RBS) known as SD sequence upstream of the start codon, while in eukaryotes the small ribosomal subunit binds to the 7-methylguanosine cap at the 5' end of the mRNA. The SD sequence in prokaryotes aids in the proper aligning of the ribosome subunit to the start codon (AUG). In eukaryotes, the small ribosomal subunit bound at the 5' end scans the mRNA in the 5' → 3' direction to locate the Kozak sequence (ACCAUGG) which contains the start codon. In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, the large ribosome subunit is recruited to the mRNA once the start codon is recognized to initiate the process of translation. (Tungekar et al., 2021)

Figure 8. Schematic representation of initiation of translation in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. In prokaryotes, the small ribosome subunit binds to the ribosome-binding site (RBS) known as SD sequence upstream of the start codon, while in eukaryotes the small ribosomal subunit binds to the 7-methylguanosine cap at the 5' end of the mRNA. The SD sequence in prokaryotes aids in the proper aligning of the ribosome subunit to the start codon (AUG). In eukaryotes, the small ribosomal subunit bound at the 5' end scans the mRNA in the 5' → 3' direction to locate the Kozak sequence (ACCAUGG) which contains the start codon. In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, the large ribosome subunit is recruited to the mRNA once the start codon is recognized to initiate the process of translation. (Tungekar et al., 2021)

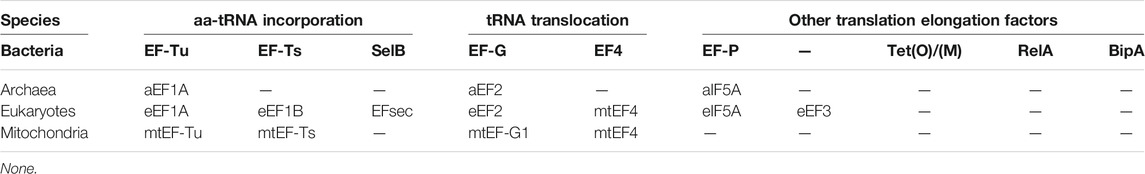

Elongation and Termination

The elongation and termination phases are relatively similar, but differ in the factors involved.

- Prokaryotes: Use elongation factors EF-Tu and EF-G and termination factors RF1 and RF2.

- Eukaryotes: Use elongation factors eEF1 and eEF2 and termination factors eRF1 and eRF3.

Table 1. Translation elongation factors among bacteria, archaea, eukaryotes and mitochondria. (Xu et al., 2022)

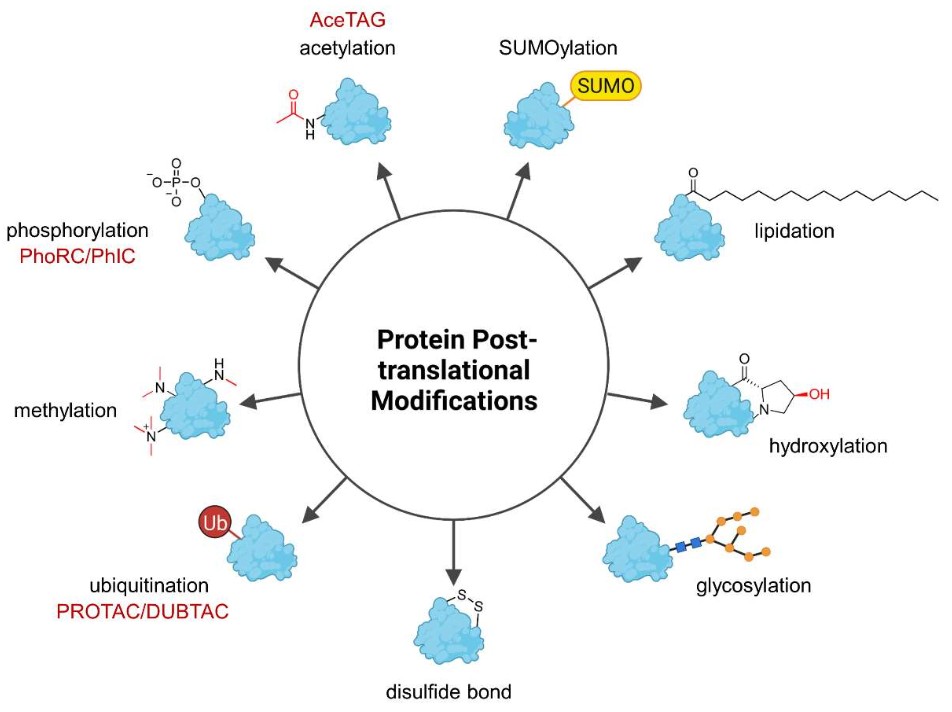

Post-Translational Modifications

After translation, proteins often undergo modifications to become fully functional.

- Prokaryotes: perform limited modifications (e.g., chaperone-assisted folding, signal peptide cleavage).

- Eukaryotes: Undergo extensive modifications that improve protein stability, function, and localization. These PTMs include:

- Phosphorylation, glycosylation, acetylation, methylation, and ubiquitination

- Protein targeting via the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus.

Figure 9. Overview of the most common posttranslational protein modifications (PTMs). (Heitel, 2023)

Figure 9. Overview of the most common posttranslational protein modifications (PTMs). (Heitel, 2023)

Regulation of Protein Synthesis

Gene Regulation

Gene expression is regulated differently in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells.

- Prokaryotes: Use operons (e.g., the lac operon) to regulate multiple genes simultaneously.

- Eukaryotes: Have more complex regulatory systems, including:

- Enhancers/silencers and epigenetic modifications (e.g., DNA methylation) regulate spatial and temporal gene expression.

- MicroRNAs (miRNAs) inhibit translation and add post-transcriptional control. This complexity supports specialized cell functions and long-term developmental programs.

Figure 10. DNA gene structure of a eukaryote. (Shafee and Lowe, 2017)

Figure 10. DNA gene structure of a eukaryote. (Shafee and Lowe, 2017)

Response to Environmental Changes

Prokaryotic cells rapidly adjust gene expression in response to environmental changes, whereas eukaryotic cells rely on long-term regulatory mechanisms.

Applications and Implications

| Applications | Implications | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Synthesis in Prokaryotes | Protein Synthesis in Eukaryotes | Protein Synthesis in Prokaryotes | Protein Synthesis in Eukaryotes |

| Antibiotics Development: Understanding prokaryotic protein synthesis has led to the development of antibiotics like tetracyclines and macrolides, which inhibit bacterial ribosomes without affecting eukaryotic cells. | Therapeutic Protein Production: Eukaryotic cells are used to produce therapeutic proteins like monoclonal antibodies, growth factors, and vaccines, where post-translational modifications (like glycosylation) are crucial for activity. | Antibiotic Resistance: Misuse of antibiotics can lead to the development of bacterial strains that are resistant to treatments that target protein synthesis, highlighting the need for careful use of antibiotics. | Cancer Research: Mutations in genes that regulate protein synthesis can lead to cancer. Targeting the pathways involved in protein synthesis is a promising approach to developing cancer therapies. |

| Biotechnology: Prokaryotes (like E. coli) are commonly used in recombinant DNA technology to express proteins of interest, such as enzymes or therapeutic proteins. | Gene Therapy: Understanding eukaryotic protein synthesis is essential for developing gene therapy strategies, where therapeutic proteins are introduced to correct genetic disorders. | Biotechnological Advancements: The efficient use of prokaryotes for protein production in research, medicine and industrial applications remains an essential tool, although optimizing protein expression remains a challenge due to the potential inefficiency or toxicity of recombinant proteins. | Molecular Medicine: Diseases caused by faulty protein synthesis, such as various neurodegenerative diseases, highlight the importance of understanding the process at the molecular level to develop potential treatments. |

| Research on Gene Regulation: Prokaryotic models help understand how genes are regulated at the translational level, which is crucial for studying bacterial responses to stress or environmental changes. | Protein Folding Studies: In diseases like Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and cystic fibrosis, protein misfolding and aggregation are key factors. Understanding eukaryotic protein synthesis and quality control mechanisms is vital for developing treatments. | Environmental and Agricultural Impacts: Understanding how eukaryotic cells synthesize proteins allows for better crop engineering, including the production of valuable proteins in plants and animals, with applications in food security and biotechnology. | |

Advantages and Limitations of Each System

| Aspect | Prokaryotes | Eukaryotes |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages | Speed and Efficiency: Rapid protein synthesis due to coupled transcription and translation. | Complex Post-Translational Modifications: Can perform modifications like glycosylation, phosphorylation, etc. |

| Simplicity: Simpler machinery, easier to manipulate for genetic studies and industrial purposes. | Protein Folding and Assembly: Specialized organelles like ER and Golgi aid proper folding and assembly. | |

| Cost-Effective for Recombinant Protein Production: Ideal for large-scale, low-cost production in organisms like E. coli. | Expression of Complex Proteins: Better suited for expressing proteins requiring complex modifications. | |

| No Introns: mRNA is typically ready for translation without the need for splicing. | Protein Secretion: Can secrete proteins, simplifying purification. | |

| Limitations | Lack of Post-Translational Modifications: Unable to perform complex modifications, limiting functionality of some proteins. | Slower Protein Synthesis: More time-consuming due to compartmentalization of transcription and translation. |

| Codon Bias and Protein Folding Issues: Issues with codon recognition and protein misfolding for some eukaryotic proteins. | More Complex and Expensive: Requires specialized conditions and is more costly for large-scale production. | |

| Toxicity of Recombinant Proteins: Recombinant proteins can be toxic to prokaryotic cells, reducing yield. | Cell Line Development: Establishing stable eukaryotic cell lines can be time-consuming and challenging. | |

| Gene Delivery Challenges: Introducing foreign genes into eukaryotic cells requires sophisticated techniques. | ||

| Best Use | High-throughput production of simple proteins, research, and industrial applications. | Production of complex proteins requiring post-translational modifications, therapeutic proteins, and research. |

In summary, protein synthesis in prokaryotes and eukaryotes shares a basic framework, but exhibits crucial differences. Prokaryotic systems are streamlined for rapid, efficient transcription and translation, often coupling these processes. In contrast, eukaryotic systems involve complex regulation, compartmentalization, and extensive post-transcriptional and post-translational modifications. These differences allow for greater control over gene expression and protein diversity in eukaryotic organisms. Understanding these differences is essential for fields such as molecular biology, biotechnology, and medicine, where targeted manipulation of protein synthesis is a key area of research and application.

Creative Biostructure's team of experts offers comprehensive protein engineering and protein expression services, with a range of expression systems to choose from, including mammalian cell systems, bacterial cell systems, and cell-free systems. Contact us today to discuss your project!

References

- Abril AG, Rama JLR, Sánchez-Pérez A, Villa TG. Prokaryotic sigma factors and their transcriptional counterparts in Archaea and Eukarya. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;104(10):4289-4302. doi:10.1007/s00253-020-10577-0

- Barba-Aliaga M, Alepuz P, Pérez-Ortín JE. Eukaryotic RNA polymerases: the many ways to transcribe a gene. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:663209. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2021.663209

- Campofelice A, Lentini L, Di Leonardo A, et al. Strategies against nonsense: oxadiazoles as translational readthrough-inducing drugs (TRIDS). IJMS. 2019;20(13):3329. doi:0.3390/ijms20133329

- Heitel P. Emerging TACnology: heterobifunctional small molecule inducers of targeted posttranslational protein modifications. Molecules. 2023;28(2):690. doi:10.3390/molecules28020690

- Shafee T, Lowe R, La Trobe Institute for Molecular Science, Melbourne, Australia. Eukaryotic and prokaryotic gene structure. Wiki J Med. 2017;4(1). doi:10.15347/wjm/2017.002

- Tungekar AA, Castillo-Corujo A, Ruddock LW. So you want to express your protein in Escherichia coli ? Mattanovich D, Ivan Nikel P, eds. Essays in Biochemistry. 2021;65(2):247-260. doi:10.1042/EBC20200170