Bioconjugation refers to the chemical process of covalently linking biological molecules (e.g., proteins, nucleic acids, carbohydrates) to synthetic molecules (e.g., polymers, fluorescent dyes, drugs) or other biomolecules. This interdisciplinary technique bridges chemistry, biology, and materials science, enabling applications such as targeted drug delivery, diagnostic imaging, and structural biology research. By creating hybrid molecules with tailored functionalities, bioconjugation has become indispensable in modern biotechnology.

Figure 1. Process of bioconjugation. (Weng et al., 2020)

Figure 1. Process of bioconjugation. (Weng et al., 2020)

How Bioconjugation Works?

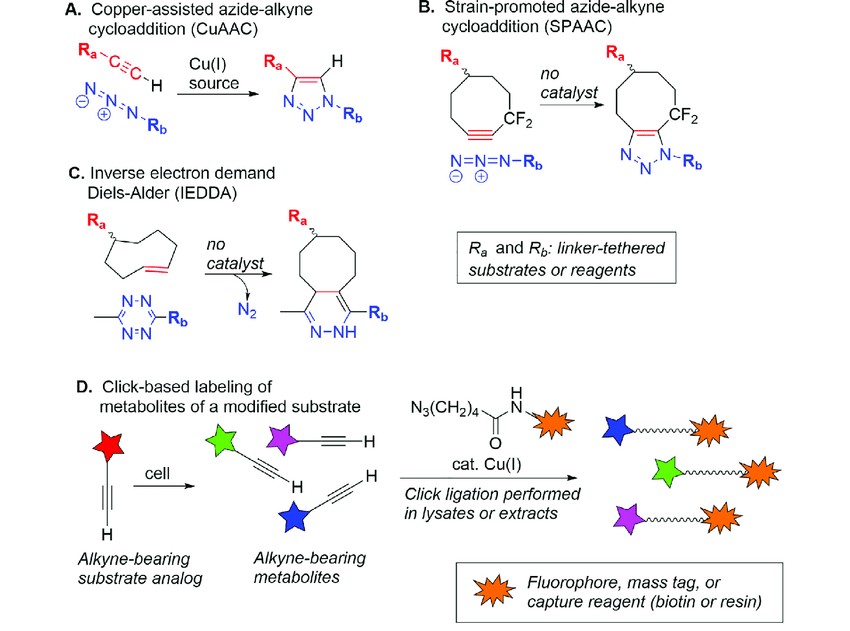

Bioconjugation is a chemical strategy that forms stable covalent bonds between two molecules, at least one of which is a biomolecule. This technique is central to several fields, including medicine, diagnostics, biocatalysis, and materials science. Modified biomolecules resulting from bioconjugation can serve multiple functions, such as tracking cellular events, elucidating enzyme functions, determining protein distribution, imaging specific biomarkers, and delivering drugs to targeted cells. In addition, bioconjugation has gained importance in nanotechnology, as exemplified by bioconjugated quantum dots.

Functional Group Targeting

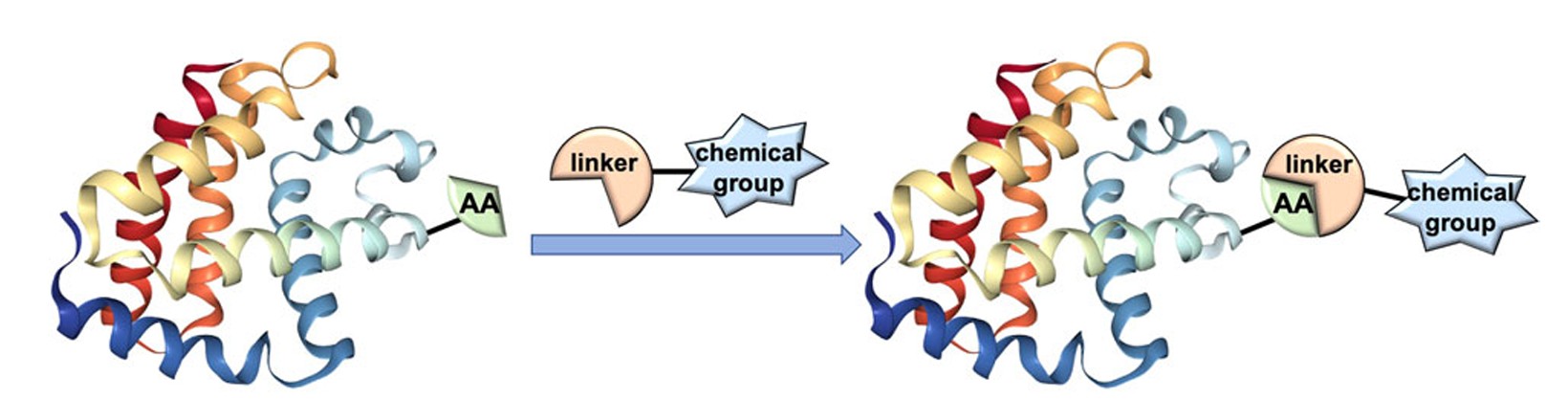

Bioconjugation techniques often target specific functional groups on biomolecules to achieve selective modification:

- Amine-reactive reagents: These reagents, such as N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) esters, react with primary amines found in lysine residues or at the N-termini of proteins. The reaction typically occurs at pH 8–9, forming stable amide bonds.

- Thiol-reactive reagents: Cysteine residues containing thiol groups are targeted using reagents such as maleimides that form stable thioether bonds. This specificity is advantageous due to the relatively low abundance of free cysteine residues on protein surfaces.

- Carbohydrate-specific: Oxidized glycans on glycoproteins, such as antibodies, contain aldehyde groups that can be targeted by hydrazide derivatives to form hydrazone bonds.

Figure 2. Common bioconjugation reactions that allow the attachment of bifunctional chelators to the nanomaterial surface. (A) Amine-based conjugation, (B) carboxylic acid-based conjugation, (C) thiol-based conjugation and (D) click chemistry conjugation. (Pellico et al., 2021)

Figure 2. Common bioconjugation reactions that allow the attachment of bifunctional chelators to the nanomaterial surface. (A) Amine-based conjugation, (B) carboxylic acid-based conjugation, (C) thiol-based conjugation and (D) click chemistry conjugation. (Pellico et al., 2021)

Click Chemistry

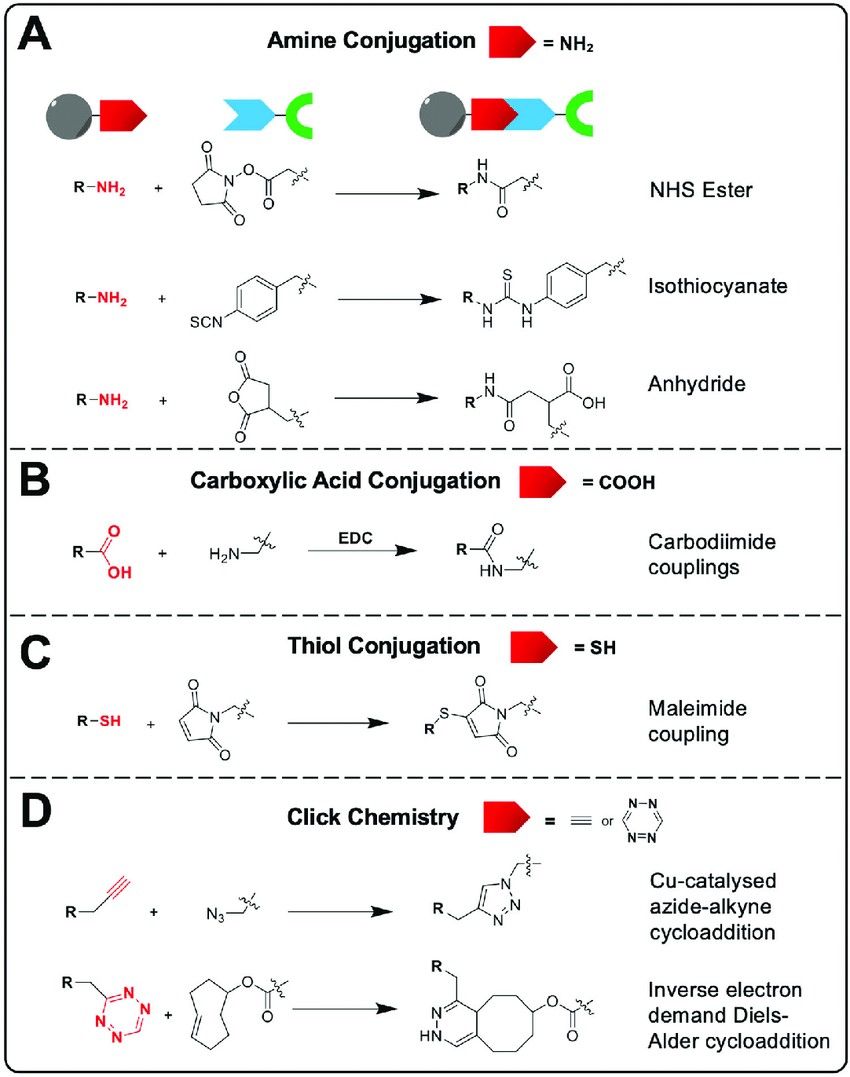

Click chemistry involves bioorthogonal reactions that proceed rapidly and selectively under mild conditions:

- Copper-Catalyzed Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition (CuAAC): This reaction involves the copper(I)-catalyzed coupling of azides and terminal alkynes to form 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazoles. It is widely used for the labeling of biomolecules due to its robustness and specificity.

- Strain-Promoted Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition (SPAAC): To circumvent the cytotoxicity associated with copper catalysts, SPAAC uses strained cyclooctynes that react with azides without the need for a catalyst, enabling applications in live-cell labeling.

Figure 3. Overview of click chemistry and illustration of application to metabolomics. (A) Copper-assisted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC). (B) Strain-promoted azidealkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC). (C) Inverse electron demand Diels-Alder reaction (IEDDA). (D) Identifying metabolites using alkyne-containing analogs of substrates. (Sakallioglu et al., 2021)

Figure 3. Overview of click chemistry and illustration of application to metabolomics. (A) Copper-assisted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC). (B) Strain-promoted azidealkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC). (C) Inverse electron demand Diels-Alder reaction (IEDDA). (D) Identifying metabolites using alkyne-containing analogs of substrates. (Sakallioglu et al., 2021)

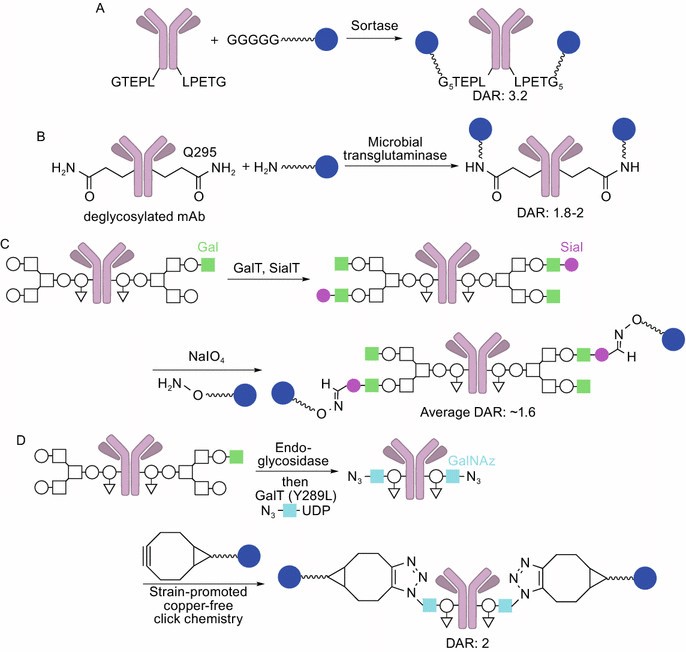

Enzyme-Mediated Conjugation

Enzymes can facilitate site-specific bioconjugation:

- Sortase A: This enzyme recognizes the LPXTG motif in proteins and catalyzes the transpeptidation reaction, allowing for the attachment of desired molecules to specific sites.

- Transglutaminases: These enzymes catalyze the formation of covalent bonds between glutamine residues and various primary amines, enabling the conjugation of amine-containing molecules to proteins.

- Formylglycine-Generating Enzymes (FGEs): FGEs convert specific cysteine residues within a recognition sequence into formylglycine, introducing an aldehyde functional group. This aldehyde can then react with hydrazide or aminooxy compounds, facilitating site-specific labeling.

Figure 4. Site-specific (chemo)enzymatic conjugation. (A) Sortase-mediated conjugation. Sortase attaches oligoglycine-functionalized linkers to LPETG tags on the mAb. (B) Microbial transglutaminase-mediated conjugation. The enzyme attaches an ADC linker possessing a primary amine to Q295 of the heavy chain (DAR: 1.8–2, high homogeneity). (C) Conjugation using β-1,4-galactosyltransferase (GalT) and α-2,6-sialyltransferase (SialT) (light green square: β-1,4-galactose, magenta circle: sialic acid). The aldehyde groups installed react with alkoxyamine-functionalized linkers (average DAR: ~1.6). (D) GlycoConnect technology using endoglycosidase, galactosyltransferase, and N-azidoacetylgalactosamine (GalNAz, light blue square). The azide groups installed react with strained cyclooctyne-functionalized linkers (DAR: 2, high homogeneity). (Tsuchikama and An, 2018)

Figure 4. Site-specific (chemo)enzymatic conjugation. (A) Sortase-mediated conjugation. Sortase attaches oligoglycine-functionalized linkers to LPETG tags on the mAb. (B) Microbial transglutaminase-mediated conjugation. The enzyme attaches an ADC linker possessing a primary amine to Q295 of the heavy chain (DAR: 1.8–2, high homogeneity). (C) Conjugation using β-1,4-galactosyltransferase (GalT) and α-2,6-sialyltransferase (SialT) (light green square: β-1,4-galactose, magenta circle: sialic acid). The aldehyde groups installed react with alkoxyamine-functionalized linkers (average DAR: ~1.6). (D) GlycoConnect technology using endoglycosidase, galactosyltransferase, and N-azidoacetylgalactosamine (GalNAz, light blue square). The azide groups installed react with strained cyclooctyne-functionalized linkers (DAR: 2, high homogeneity). (Tsuchikama and An, 2018)

Bioconjugation in Structural Biology

Bioconjugation is a fundamental technique in structural biology that facilitates the detailed analysis of biomolecular structures and dynamics. By covalently linking specific probes or tags to target molecules, researchers can improve the visualization and understanding of complex biological systems.

Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) Sample Preparation

In cryo-EM, preserving the native state of biological specimens is crucial. Bioconjugation aids in this by enabling the attachment of specific markers or stabilizers to target molecules:

- Nanogold Labeling: Attaching gold nanoparticles to antibodies or other binding proteins allows for the precise localization of target proteins within large complexes. The electron-dense nature of gold enhances contrast in cryo-EM images, aiding in the identification and analysis of specific components within heterogeneous assemblies.

- Bifunctional Crosslinkers: These reagents covalently link interacting proteins, stabilizing transient or weak interactions that might otherwise dissociate during sample preparation. This stabilization is essential for capturing accurate structural snapshots of dynamic protein complexes.

X-ray Crystallography

Determining the three-dimensional structures of proteins and nucleic acids through X-ray crystallography often requires phase information, which can be challenging to obtain directly. Bioconjugation provides solutions to this problem:

- Heavy Atom Derivatization: The introduction of heavy atoms into the crystal lattice facilitates phase determination by methods such as Multiple Isomorphic Replacement (MIR) or Anomalous Dispersion. For example, conjugation of iodoacetamide to cysteine residues introduces iodine atoms into the protein, which serve as effective anomalous scatterers for phase calculations.

Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)

FRET is a powerful technique for monitoring molecular interactions and conformational changes in real-time. Bioconjugation enables the precise placement of fluorescent probes necessary for FRET analysis:

- Dye-Conjugated Biomolecules: By attaching fluorescent dyes to specific sites on proteins or nucleic acids, researchers can observe energy transfer events that report on distances and dynamics at the nanometer scale. This approach is invaluable for studying processes such as GTPase activation in signaling pathways, where conformational changes are critical for function.

Applications of Bioconjugation

Therapeutic Development

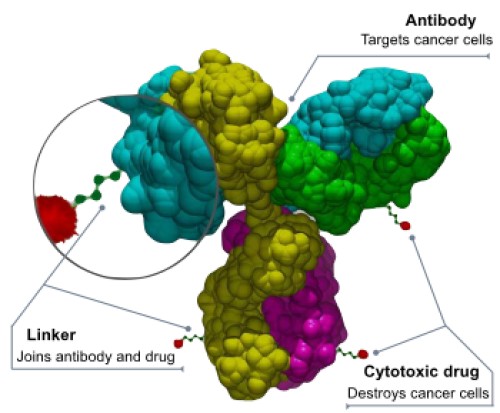

- Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs): ADCs are engineered molecules that combine the specificity of monoclonal antibodies with the potency of cytotoxic drugs. By connecting these components through stable chemical linkers, ADCs selectively deliver chemotherapeutic agents to cancer cells while minimizing damage to healthy tissue. For example, trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) targets HER2-positive breast cancer cells by delivering the cytotoxic agent emtansine directly to the tumor site. Recent advances include the development of datopotamab deruxtecan (Datroway), which is approved for the treatment of metastatic HR-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer. This ADC has demonstrated efficacy in extending progression-free survival with a favorable safety profile.

Figure 5. Schematic structure of an antibody–drug conjugate (ADC).

Figure 5. Schematic structure of an antibody–drug conjugate (ADC).

- PEGylation: The addition of polyethylene glycol (PEG) to therapeutic proteins, known as PEGylation, improves their pharmacokinetic properties. PEGylation increases the molecular size of the protein, which reduces renal clearance and proteolytic degradation, thereby prolonging the half-life of the protein in the circulation. This modification also reduces immunogenicity and improves solubility. Certolizumab pegol (Cimzia), a PEGylated antibody fragment targeting tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), is used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Its PEGylation enhances therapeutic efficacy by improving stability and bioavailability.

Diagnostics

- Lateral Flow Assays: These point-of-care diagnostic tests use bioconjugation to rapidly detect specific analytes. Gold nanoparticles conjugated to antibodies serve as visible markers, indicating the presence of pathogens such as SARS-CoV-2 within minutes. Conjugation of antibodies to gold nanoparticles enables visual detection of antigen-antibody interactions, facilitating rapid and accessible diagnostics.

- Quantum Dot Labeling: Quantum dots (QDs) are semiconductor nanocrystals that, when conjugated to biomolecules such as DNA probes, enable sensitive and multiplexed imaging of biological targets. Their unique optical properties, including size-tunable emission spectra and high photostability, make them ideal for the simultaneous detection of multiple tumor biomarkers. For example, QD-based lateral flow immunoassays have been developed for rapid and sensitive diagnosis of infectious diseases, improving the performance of traditional assays.

Structural Biology Innovations

- DNA-PAINT: This super-resolution microscopy technique is based on the transient hybridization of dye-labeled DNA strands to complementary sequences attached to target molecules. The dynamic binding and unbinding events generate fluorescence signals that, when precisely localized, achieve imaging resolutions of less than 10 nanometers. DNA-PAINT enables precise visualization of molecular structures and interactions at the nanoscale, advancing our understanding of complex biological systems.

- Site-Specific Spin Labeling: Incorporation of nitroxide radicals into specific protein sites allows electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy studies of protein dynamics. This approach provides insight into conformational changes, folding, and interactions by monitoring the magnetic properties of the spin labels. Site-specific labeling ensures that the spin labels report on defined regions of the protein, providing detailed information on structural rearrangements and functional mechanisms.

Case Study

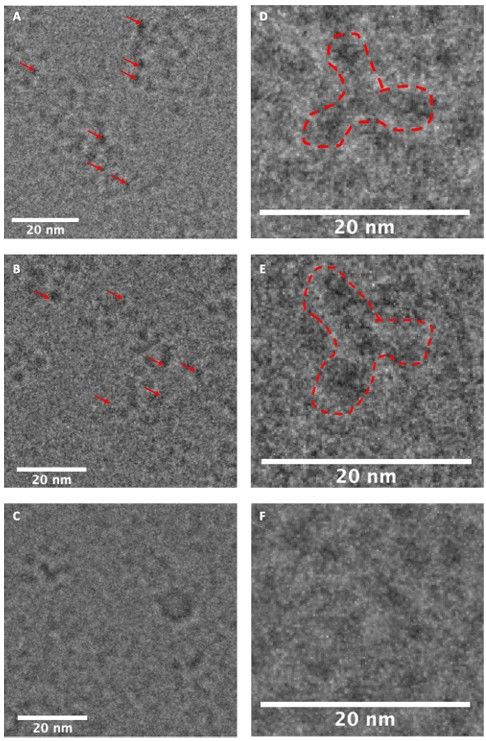

Case 1: Bioconjugation of Au25 Nanocluster to Monoclonal Antibody at Tryptophan

This study describes the bioconjugation of Au25 nanoclusters to monoclonal antibodies at tryptophan (Trp) residues for the development of high-resolution probes for cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and tomography (cryo-ET). A new Trp-selective bioconjugation method using hydroxylamine reagents was developed that allows the modification of acid-sensitive proteins such as antibodies. In the two-step procedure, azide groups were introduced to the protein by Trp-selective bioconjugation, followed by strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) to attach redox-sensitive Au25 nanoclusters.

Cryo-EM analysis confirmed the presence of gold clusters in the conjugates, but challenges arose due to the small size of the Au25 nanoclusters and their low electron density compared to uranyl acetate staining. Samples had to be diluted for optimal protein dispersion, and the labeled proteins showed small black inclusions corresponding to the Au25 clusters. However, single particle analysis was unsuccessful, likely due to the small size and flexibility of the antibody. The results suggest that this bioconjugation method is promising for high-resolution imaging, but requires further optimization.

Figure 6. Cryo-EM images of Au25 nanocluster-conjugated trastuzumab at Trp (13) or Lys (14) and unmodified trastuzumab. (A) 13. (B)14. (C) Unmodified trastuzumab. Red arrows in A and B indicate Au25 nanoclusters. (D) Magnified picture of a single particle of13 (dashed red line). (E) Magnified picture of a single particle of 14 (dashed red line). (F) Magnified picture of trastuzumab. A single particle was not clearly visible due to the absence of Au clusters. (Malawska et al., 2023)

Figure 6. Cryo-EM images of Au25 nanocluster-conjugated trastuzumab at Trp (13) or Lys (14) and unmodified trastuzumab. (A) 13. (B)14. (C) Unmodified trastuzumab. Red arrows in A and B indicate Au25 nanoclusters. (D) Magnified picture of a single particle of13 (dashed red line). (E) Magnified picture of a single particle of 14 (dashed red line). (F) Magnified picture of trastuzumab. A single particle was not clearly visible due to the absence of Au clusters. (Malawska et al., 2023)

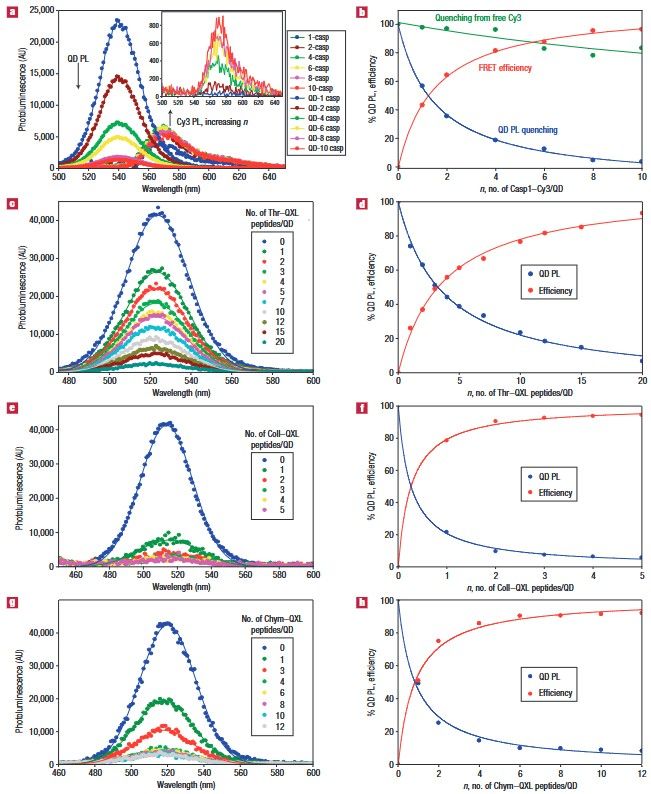

Case 2: Proteolytic Activity Monitored by Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer Through Quantum-Dot–Peptide Conjugates

This study presents luminescent quantum dot (QD) bioconjugates designed to detect proteolytic activity via fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). Researchers developed modular peptide structures that allow dye-labeled protease substrates—specific for caspase-1, thrombin, collagenase, and chymotrypsin—to be attached to QDs. The efficiency of FRET within these nanoassemblies is tunable, enabling quantitative enzymatic assays under varying conditions.

In this study, enzymatic kinetics, including rate, Michaelis-Menten parameters, and inhibition mechanisms, were measured using QD-thrombin conjugates to screen inhibitory compounds. The results indicate that protease activity can be effectively monitored by FRET-driven photoluminescence (PL) changes. Increasing the number of dye-labeled peptides per QD resulted in significant quenching of QD emission, demonstrating non-radiative energy transfer.

Different dye acceptors such as Cy3 and QXL-520 were used, with smaller peptides showing higher FRET efficiencies. The results suggest that this technology could be adapted beyond proteases to monitor other enzymatic modifications, providing a valuable tool for biochemical and diagnostic applications.

Figure 7. FRET efficiency data from QD–peptide nanosensors. a, Deconvoluted PL spectra resulting from assembling an increasing number of Casp1–Cy3 per 538 nm QD. The inset shows the Cy3 PL contribution owing to direct excitation from the equivalent amount of free Casp1–Cy3 peptide. b, QD PL quenching reported as a percentage in blue from a. The corresponding FRET efficiencies as a function of Casp1–Cy3-to-QD ratio are shown in red. A control of QD PL loss versus the equivalent amount of free Cy3 is a shown in green. c, PL spectra for an increasing ratio of Thr–QXL per 522 nm QD. d, Plot of QD PL loss (percentage) versus Thr–QXL to QD ratio (blue) and the corresponding FRET efficiency versus n (red). e, Titration of 510 nm QDs with an increasing number of Coll–QXL and f, the corresponding QD PL loss and FRET efficiency versus n. g, Titration of 510 nm QDs with an increasing ratio of Chym–QXL peptides and h, corresponding QD PL loss versus n and FRET efficiency. (Medintz et al., 2006)

Figure 7. FRET efficiency data from QD–peptide nanosensors. a, Deconvoluted PL spectra resulting from assembling an increasing number of Casp1–Cy3 per 538 nm QD. The inset shows the Cy3 PL contribution owing to direct excitation from the equivalent amount of free Casp1–Cy3 peptide. b, QD PL quenching reported as a percentage in blue from a. The corresponding FRET efficiencies as a function of Casp1–Cy3-to-QD ratio are shown in red. A control of QD PL loss versus the equivalent amount of free Cy3 is a shown in green. c, PL spectra for an increasing ratio of Thr–QXL per 522 nm QD. d, Plot of QD PL loss (percentage) versus Thr–QXL to QD ratio (blue) and the corresponding FRET efficiency versus n (red). e, Titration of 510 nm QDs with an increasing number of Coll–QXL and f, the corresponding QD PL loss and FRET efficiency versus n. g, Titration of 510 nm QDs with an increasing ratio of Chym–QXL peptides and h, corresponding QD PL loss versus n and FRET efficiency. (Medintz et al., 2006)

Challenges and Future Directions

- Specificity and Stability: Nonspecific conjugation remains an obstacle. Advances in site-selective methods, such as engineered unnatural amino acids (e.g., p-azidophenylalanine), are improving precision.

- Scalability: Industrial-scale bioconjugation requires robust processes. Microfluidic systems and automated synthesizers, similar to chromatographic optimization strategies in oligonucleotide analysis, are being adapted for high-throughput conjugation.

- Multifunctional Conjugates: Combining crosslinking with stimuli-responsive linkers (e.g., pH-labile bonds) enables "smart" drug delivery systems. This mirrors the dynamic flexibility of heat exchanger networks, where adaptability to perturbations is critical.

Creative Biostructure is experts in structural biology analysis, providing cutting-edge solutions for the precise study of your biological interactions. Using advanced techniques such as cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET), and Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), we enable high-resolution visualization of molecular structures and dynamic interactions. Contact us today to learn more about how we can support your bioconjugation research.

References

- King TA, Rodríguez Pérez L, Flitsch SL. Application of biocatalysis for protein bioconjugation. In: Comprehensive Chirality. Elsevier; 2024:389-437. doi:10.1016/B978-0-32-390644-9.00122-0

- Malawska KJ, Takano S, Oisaki K, et al. Bioconjugation of Au25 nanocluster to monoclonal antibody at tryptophan. Bioconjugate Chem. Published online March 9, 2023:acs.bioconjchem.3c00069. doi:10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.3c00069

- Medintz IL, Clapp AR, Brunel FM, et al. Proteolytic activity monitored by fluorescence resonance energy transfer through quantum-dot–peptide conjugates. Nature Mater. 2006;5(7):581-589. doi:10.1038/nmat1676

- Pellico J, Gawne PJ, T. M. De Rosales R. Radiolabelling of nanomaterials for medical imaging and therapy. Chem Soc Rev. 2021;50(5):3355-3423. doi:10.1039/D0CS00384K

- Sakallioglu IT, Barletta RG, Dussault PH, Powers R. Deciphering the mechanism of action of antitubercular compounds with metabolomics. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 2021;19:4284-4299. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2021.07.034

- Tsuchikama K, An Z. Antibody-drug conjugates: recent advances in conjugation and linker chemistries. Protein Cell. 2018;9(1):33-46. doi:10.1007/s13238-016-0323-0

- Weng Y, Song C, Chiang CW, Lei A. Single electron transfer-based peptide/protein bioconjugations driven by biocompatible energy input. Commun Chem. 2020;3(1):171. doi:10.1038/s42004-020-00413-x