DNA synthesis is a fundamental biological process that ensures the transmission of genetic information from one generation to the next. In living organisms, DNA synthesis occurs through a tightly regulated enzymatic mechanism during DNA replication, involving several key enzymes such as DNA polymerases, helicases, primases, and ligases. In addition to natural processes, laboratory techniques have been developed to synthesize DNA for research, medical, and industrial applications. These include chemical synthesis of oligonucleotides, enzymatic DNA amplification, and gene editing technologies such as CRISPR-Cas9.

Creative Biostructure specializes in the analysis of biological structures, offering comprehensive DNA structure characterization services. Using advanced techniques such as NMR spectroscopy, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assay, Raman spectroscopy, and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy, we provide precise insights into DNA structure. Additionally, we offer cutting-edge DNA origami and self-assembly service, enabling innovative applications in nanotechnology and molecular engineering.

Natural DNA Synthesis

Mechanism of DNA Synthesis

DNA synthesis, also known as DNA replication, is a highly coordinated and regulated process that ensures that genetic information is accurately copied and passed on to daughter cells. This mechanism follows the semi-conservative model, meaning that each newly synthesized DNA molecule consists of one original (parental) strand and one newly synthesized strand.

Base-Pairing and Directionality

The fidelity of DNA replication is based on the principle of complementary base pairing, in which adenine (A) binds to thymine (T) through two hydrogen bonds and cytosine (C) binds to guanine (G) through three hydrogen bonds. This base pairing ensures that the genetic code is accurately duplicated.

DNA synthesis occurs exclusively in the 5' to 3' direction, meaning that new nucleotides are always added to the 3' hydroxyl (-OH) end of the growing strand. This directionality is due to the enzymatic activity of DNA polymerases, which catalyze the formation of phosphodiester bonds between incoming deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) and the growing DNA strand.

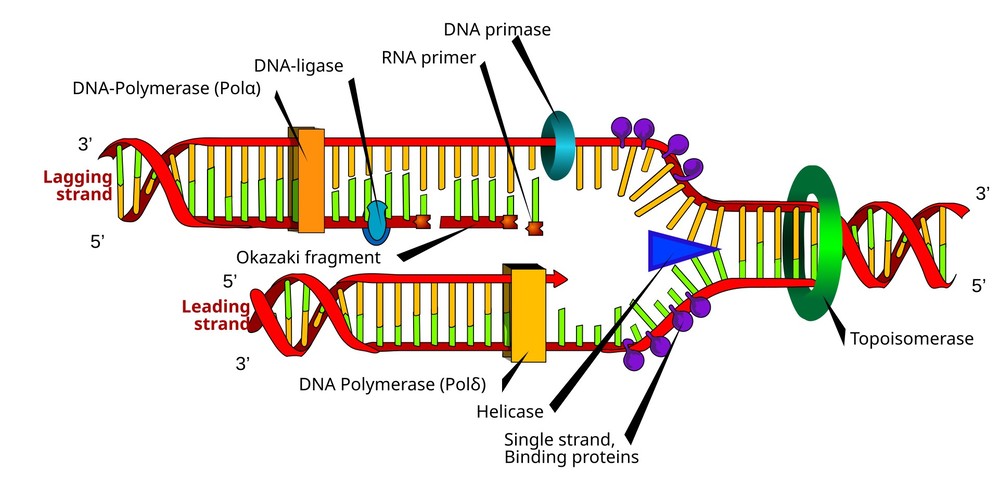

Leading Strand vs. Lagging Strand Synthesis

Since DNA is antiparallel, the two strands run in opposite directions. This leads to two different modes of DNA synthesis:

- Leading Strand Synthesis: The leading strand is synthesized continuously in the 5' to 3' direction by DNA polymerase, following the unwinding of the DNA double helix.

- Lagging Strand Synthesis: The lagging strand is synthesized discontinuously because its template strand runs in the 5' to 3' direction, opposite to the movement of the replication fork. To overcome this, DNA synthesis occurs in small, separate segments called Okazaki fragments, which are later joined together by DNA ligase to form a continuous strand.

Coordinated synthesis of both strands ensures complete and accurate replication of the genome prior to cell division.

Figure 1. DNA replication, and the various enzymes involved.

Figure 1. DNA replication, and the various enzymes involved.

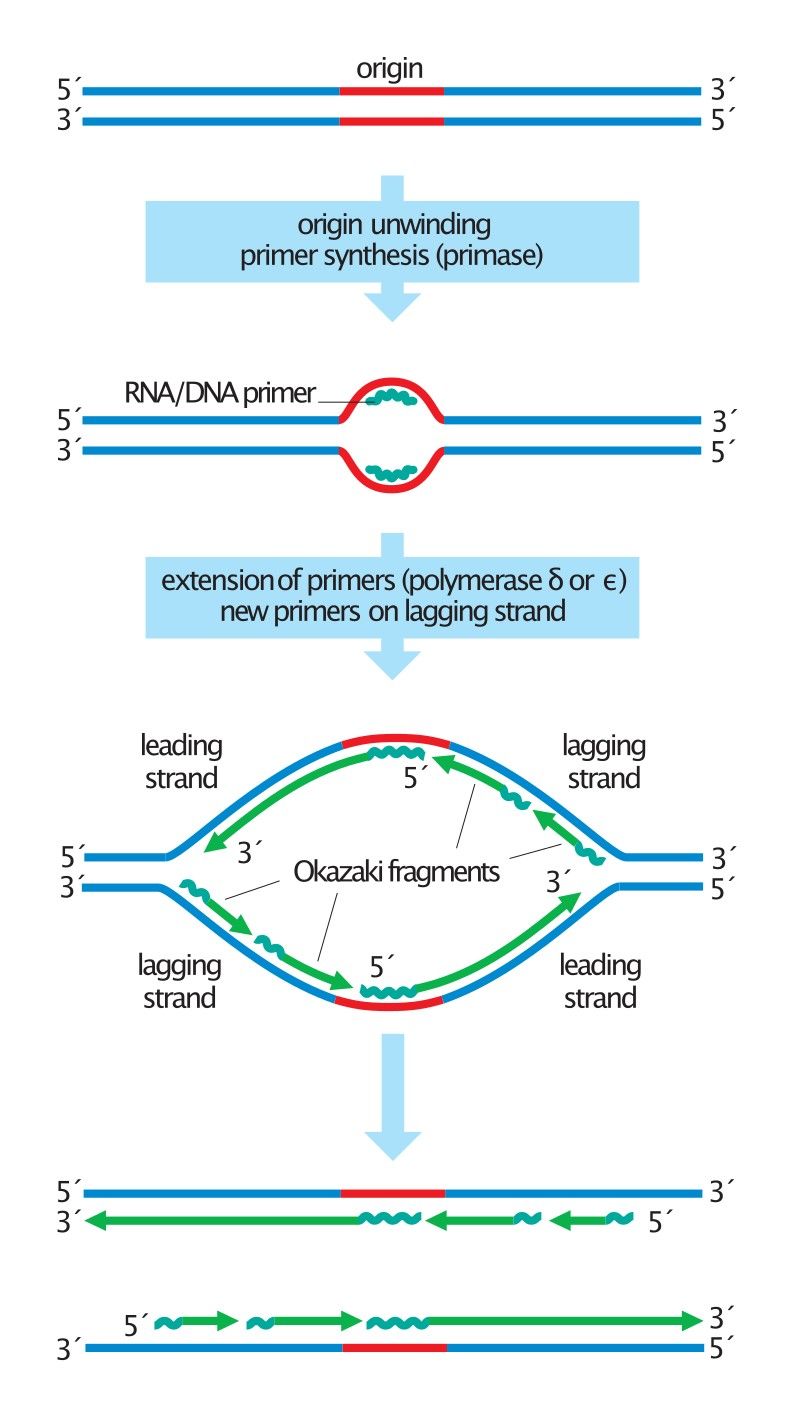

Main Steps of DNA Replication

Step 1: Initiation

The replication process begins at specific sites in the genome called origins of replication (Ori). These regions are recognized by initiator proteins, which recruit helicase and other replication factors to open the DNA helix.

Key events during initiation include:

- Unwinding of the DNA helix: DNA helicase breaks hydrogen bonds between complementary bases, separating the strands and forming a replication fork.

- Stabilization of single-stranded DNA: Single-stranded binding proteins (SSBs) bind to the exposed DNA strands, preventing them from reannealing.

- Relieving supercoiling tension: Topoisomerase enzymes introduce temporary breaks in the DNA to prevent excessive twisting and supercoiling.

- Priming DNA synthesis: Primase, an RNA polymerase, synthesizes a short RNA primer that serves as a starting point for DNA polymerase to initiate DNA synthesis.

Once the replication machinery is assembled, the process moves into the elongation phase.

Step 2: Elongation

During elongation, DNA polymerases catalyze the addition of nucleotides to the new strands of DNA using the parent strands as templates. This process is different for the leading and lagging strands:

- Leading Strand Synthesis: DNA polymerase continuously adds nucleotides in the 5' to 3' direction, following the unwinding replication fork.

- Lagging Strand Synthesis: Since DNA polymerase can only synthesize in the 5' to 3' direction, replication on the lagging strand occurs discontinuously. Okazaki fragments (short DNA fragments of ~100–200 nucleotides in eukaryotes) are synthesized and later joined by DNA ligase to create a continuous strand.

Other key processes during elongation include:

- Proofreading and Error Correction: DNA polymerase has 3' to 5' exonuclease activity, allowing it to remove incorrectly paired nucleotides and replace them with the correct bases. This ensures high replication accuracy.

- Clamp Loading and Processivity: The sliding clamp protein holds DNA polymerase on the template strand, increasing its processivity (the number of nucleotides added before dissociation).

Step 3: Termination

DNA replication terminates once the entire genome is duplicated. Termination mechanisms vary between prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms:

- In Prokaryotes: Replication ends when the two replication forks meet at specific termination sequences (Ter sites), where Tus proteins bind to halt helicase activity.

- In Eukaryotes: Replication concludes when different replication forks meet and fuse, with additional processing required for the ends of linear chromosomes.

Eukaryotic chromosomes have telomeres, repetitive DNA sequences at their ends. Because DNA polymerase cannot fully replicate the extreme ends of linear DNA, an enzyme called telomerase extends telomeres, preventing the loss of essential genetic material.

Finally, newly synthesized DNA undergoes mismatch repair to correct any remaining replication errors, ensuring the genome's integrity before cell division.

Figure 2. Overview of the steps in DNA replication. (Morgan, 2007)

Figure 2. Overview of the steps in DNA replication. (Morgan, 2007)

Laboratory Techniques for DNA Synthesis

Beyond natural DNA replication, scientists have developed artificial methods to synthesize DNA in the laboratory. These techniques play a vital role in genetic research, diagnostics, and synthetic biology.

Chemical Synthesis of DNA

Chemical synthesis of DNA is a widely used technique for producing short, single-stranded DNA sequences, commonly known as oligonucleotides. These synthetic DNA molecules serve a variety of purposes, including primers for polymerase chain reaction (PCR), probes for molecular diagnostics, and synthetic genes for research and biotechnology applications. The most common method of chemical DNA synthesis is solid-phase phosphoramidite synthesis, a highly efficient and automated process that allows precise control of nucleotide addition.

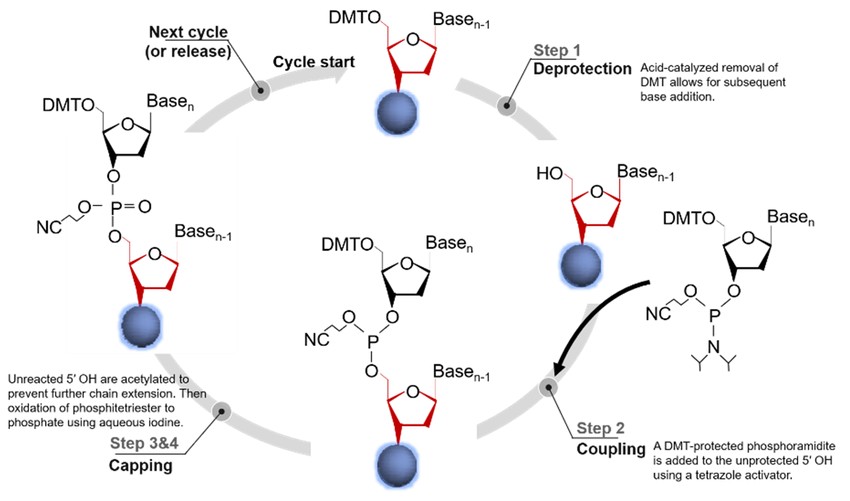

Principles of Phosphoramidite DNA Synthesis

Phosphoramidite synthesis is a stepwise chemical approach that involves the sequential addition of nucleotides to a growing DNA strand. The process occurs in a 3' to 5' direction, opposite to the natural 5' to 3' synthesis seen in biological DNA replication. This method relies on protected nucleoside phosphoramidites that prevent unwanted side reactions and ensure high-fidelity incorporation of each nucleotide.

One of the key advantages of this method is its high efficiency and specificity, with each step achieving a coupling efficiency of ~98–99%. However, due to the accumulation of errors over successive cycles, the practical limit of chemical DNA synthesis is about 200 base pairs, after which errors and incomplete synthesis become significant. Longer sequences require enzymatic assembly methods, such as Gibson assembly or polymerase-based approaches.

Main Steps of Phosphoramidite DNA Synthesis

- Deprotection: Activation of the 5' Hydroxyl Group

The synthesis begins with a solid support (typically controlled pore glass or polystyrene beads) to which the first nucleotide is attached. The 5' hydroxyl (-OH) group of the first nucleotide is protected by a dimethoxytrityl (DMT) group to prevent undesired reactions. In this step, the DMT protecting group is removed using a weak acid (e.g., trichloroacetic acid, TCA), exposing the 5'-end for nucleotide addition. - Coupling: Addition of the Next Nucleotide

A phosphoramidite-activated nucleotide (A, T, C, or G) is added to the growing chain. The nucleotide is chemically modified with a phosphoramidite group at its 3' end, which reacts with the exposed 5' hydroxyl group of the previous nucleotide. The reaction is catalyzed by an activator such as tetrazole, which promotes efficient nucleotide coupling. - Oxidation: Stabilization of the Phosphite Triester Bond

The newly formed phosphite triester bond between the nucleotides is unstable and must be oxidized to a phosphodiester bond to mimic the natural DNA backbone. This is accomplished using an oxidizing agent, such as iodine in water/pyridine/tetrahydrofuran (THF), which converts the phosphite bond to a stable phosphate group. - Capping: Blocking Unreacted Hydroxyl Groups

Some nucleotides may fail to couple during synthesis. To prevent the formation of incorrect sequences, these unreacted hydroxyl groups are capped with acetylation reagents (e.g., acetic anhydride and N-methylimidazole). This step ensures that incomplete DNA strands do not interfere with downstream applications. - Final Cleavage and Purification: Releasing the Synthesized DNA

Once the desired sequence is assembled, the DNA is cleaved from the solid support using a basic solution (e.g., ammonium hydroxide). The base-protecting groups on the nucleotides are removed, restoring the natural bases. The crude DNA is then purified using methods such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) to remove truncated or defective sequences.

Figure 3. Phosphoramidite-based oligonucleotide synthesis. (Hao et al., 2020)

Figure 3. Phosphoramidite-based oligonucleotide synthesis. (Hao et al., 2020)

Enzymatic Synthesis of DNA

Unlike chemical DNA synthesis, which is limited to short sequences, enzymatic DNA synthesis enables the generation of longer DNA fragments with high accuracy. Various enzymatic methods facilitate DNA synthesis, amplification, and modification for research, diagnostic, and therapeutic applications.

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is one of the most widely used methods for DNA amplification, allowing researchers to produce millions of copies of a specific DNA sequence in a matter of hours. Developed by Kary Mullis in 1983, PCR has revolutionized molecular biology, enabling applications in genetic analysis, forensics, diagnostics and biotechnology.

- Rolling Circle Amplification (RCA): Rolling circle amplification (RCA) is an isothermal DNA amplification method that enables the production of long single-stranded DNA molecules using a circular DNA template. RCA mimics the natural replication mechanism found in viruses and plasmids.

- Recombinant DNA Technology: Recombinant DNA technology involves the cutting, modification, and insertion of DNA fragments into host organisms for replication and expression. This method is fundamental to genetic engineering, biotechnology, and synthetic biology.

CRISPR-Cas9: Editing DNA Sequences

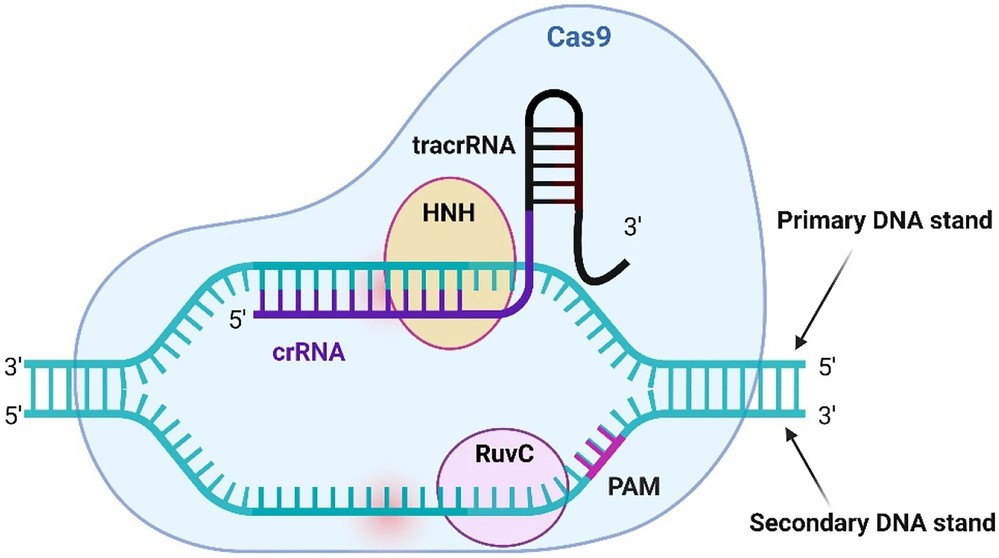

CRISPR-Cas9 is a breakthrough genome-editing technology that enables precise editing of DNA sequences. The system was adapted from the natural CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) immune system of bacteria, which fends off viral infections.

Mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9 include:

- Target Recognition: A synthetic guide RNA (gRNA) is designed to match a specific DNA sequence.

- DNA Cleavage: The Cas9 nuclease binds to the target site and introduces a double-stranded break (DSB) into the DNA.

- Repair and Editing: The cell repairs the break through non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) (often resulting in small insertions or deletions that disrupt the target gene) and homology directed repair (HDR) (using a donor DNA template to precisely insert or modify a gene).

Figure 4. Overview of the Cas9 endonuclease. TracrRNA is attached to 3′ end of crRNA and acts an anchor to the Cas9 endonuclease, this combined RNA molecule is known as a single guide RNA (sgRNA). Cas9 scans potential target DNA for the appropriate protospacer adjacent motif (PAM). When the protein finds the PAM, a confirmation change occurs leading to unwinding of the DNA allowing for interaction between the crRNA and DNA. The RuvC and HNH domains then cut the target DNA if complementary binding occurs between the guide and seed region. (Sinclair et al., 2023)

Figure 4. Overview of the Cas9 endonuclease. TracrRNA is attached to 3′ end of crRNA and acts an anchor to the Cas9 endonuclease, this combined RNA molecule is known as a single guide RNA (sgRNA). Cas9 scans potential target DNA for the appropriate protospacer adjacent motif (PAM). When the protein finds the PAM, a confirmation change occurs leading to unwinding of the DNA allowing for interaction between the crRNA and DNA. The RuvC and HNH domains then cut the target DNA if complementary binding occurs between the guide and seed region. (Sinclair et al., 2023)

Applications of Synthetic DNA

The ability to synthesize DNA artificially has numerous applications across scientific and industrial fields:

Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology

Synthetic DNA is essential for genetically modifying organisms to improve crop resilience, biofuel production, and pharmaceutical manufacturing. Recombinant DNA technology enables the creation of transgenic plants, bacteria, and animals with enhanced traits.

Medicine and Gene Therapy

Synthetic DNA plays a critical role in the treatment and diagnosis of disease. Applications include:

- Gene Therapy: Insertion of functional genes to replace defective genes in genetic disorders.

- mRNA Vaccines: COVID-19 vaccines use synthetic RNA to induce immune responses.

- Personalized Medicine: DNA-based diagnostics guide tailored treatments.

Synthetic Biology and Artificial Life

Advances in synthetic biology are enabling the creation of completely synthetic genomes. The first synthetic bacterial genome was constructed in Mycoplasma mycoides, demonstrating the potential to engineer new life forms for medical and industrial applications.

Forensic and Environmental Applications

DNA synthesis supports forensic science by enabling genetic fingerprinting and crime scene investigation. It is also used in environmental monitoring to identify microbial populations in ecosystems and in the development of biosensors to detect pollutants.

Case Study

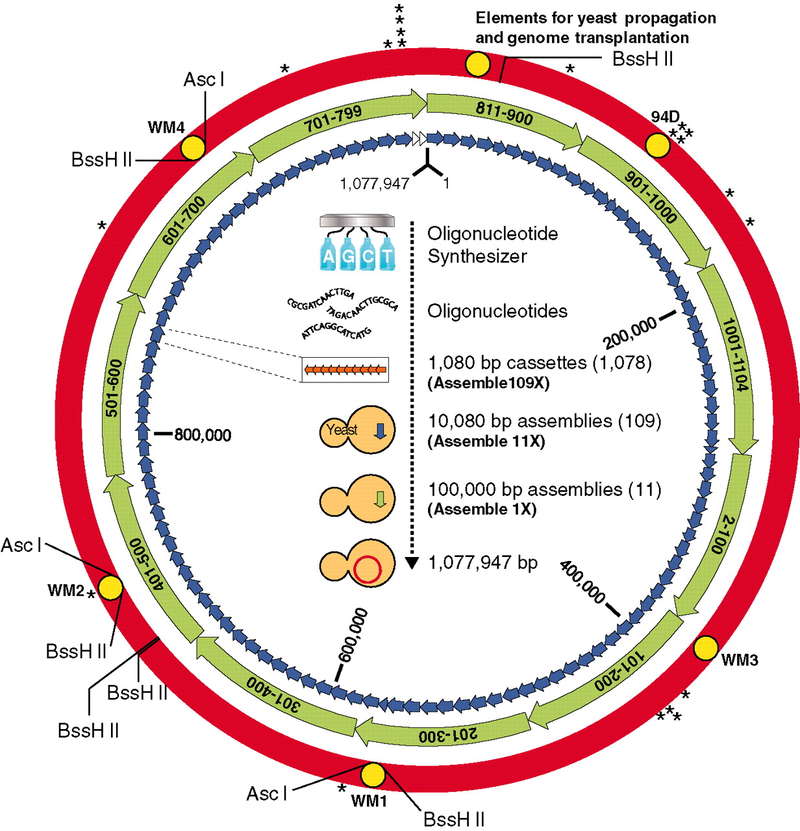

Case 1: Creation of a Bacterial Cell Controlled by a Chemically Synthesized Genome

The study reports the creation of a synthetic 1.08 million base pair genome of Mycoplasma mycoides (JCVI-syn1.0). This genome was designed, synthesized, and assembled from a digitized sequence, then transplanted into a M. capricolum recipient cell, generating new M. mycoides cells entirely controlled by the synthetic chromosome. The cells contain only the synthetic DNA, which includes "watermark" sequences, engineered gene deletions, and mutations that occurred during the assembly. These new cells exhibit the expected phenotypic traits and are capable of continuous self-replication.

Figure 5. The assembly of a synthetic M. mycoides genome in yeast. (Gibson et al., 2010)

Figure 5. The assembly of a synthetic M. mycoides genome in yeast. (Gibson et al., 2010)

Case 2: Synthetic Biology Enables Programmable Cell-Based Biosensors

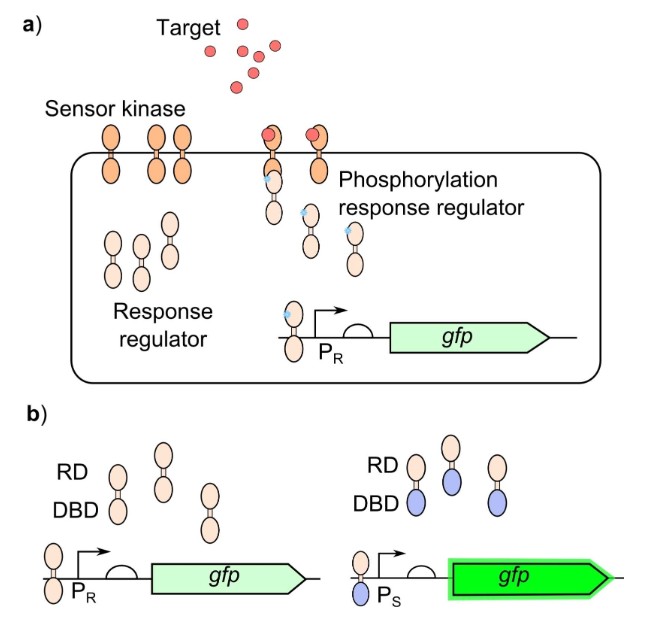

Cell-based biosensors offer low-cost, portable, and simple methods for detecting molecules, but commercial adoption has been limited by performance and specificity issues. Synthetic biology provides cutting-edge tools for building customizable cell-based biosensors with adjustable sensitivity and dynamic range to meet real-world needs. Despite progress, the integration of two-component systems (TCS)—a class of proteins responsible for sensing and responding to signals—into biosensors has been hampered by challenges in maintaining their activity in different bacterial species. TCSs work by binding to the target, activating a kinase domain that phosphorylates a response regulator, which then activates a promoter to express a gene.

Figure 6. Bacterial two‐component systems for biosensing: a) The sensor module of the TCS sensor kinase binds to the target resulting in activation of the kinase domain, the response regulator is then phosphorylated by the activated kinase domain to activate the response regulator. The response regulator will then bind to the output promoter (PR) to generate the response. b) Response regulators containing their cognate receiver domain (RD) and DNA binding domain (DBD) will bind to their cognate output promoter (PR), response regulators with swapped DBD will then bind to an alternative output promoter (PS) which generates a stronger output. (Hicks et al., 2020)

Figure 6. Bacterial two‐component systems for biosensing: a) The sensor module of the TCS sensor kinase binds to the target resulting in activation of the kinase domain, the response regulator is then phosphorylated by the activated kinase domain to activate the response regulator. The response regulator will then bind to the output promoter (PR) to generate the response. b) Response regulators containing their cognate receiver domain (RD) and DNA binding domain (DBD) will bind to their cognate output promoter (PR), response regulators with swapped DBD will then bind to an alternative output promoter (PS) which generates a stronger output. (Hicks et al., 2020)

In summary, DNA synthesis, both natural and artificial, is a cornerstone of modern biology and biotechnology. Natural DNA replication ensures the transmission of genetic information, while laboratory techniques allow researchers to synthesize and manipulate DNA for various applications.

Creative Biostructure offers comprehensive DNA structure characterization, and DNA origami and self-assembly service. Contact us today to discuss your DNA project!

References

- Frydrych-Tomczak E, Ratajczak T, Kościński Ł, et al. Structure and oligonucleotide binding efficiency of differently prepared click chemistry-type DNA microarray slides based on 3-azidopropyltrimethoxysilane. Materials. 2021;14(11):2855. doi:10.3390/ma14112855

- Gibson DG, Glass JI, Lartigue C, et al. Creation of a bacterial cell controlled by a chemically synthesized genome. Science. 2010;329(5987):52-56. doi:10.1126/science.1190719

- Hao M, Qiao J, Qi H. Current and emerging methods for the synthesis of single-stranded DNA. Genes. 2020;11(2):116. doi:10.3390/genes11020116

- Hicks M, Bachmann TT, Wang B. Synthetic biology enables programmable cell‐based biosensors. Chemphyschem. 2020;21(2):132-144. doi:10.1002/cphc.201900739

- Morgan D. The Cell Cycle: Principles of Control. Oxford University Press; 2007. ISBN 10: 0-9539181-2-2

- Sinclair F, Begum AA, Dai CC, Toth I, Moyle PM. Recent advances in the delivery and applications of nonviral CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Drug Deliv and Transl Res. 2023;13(5):1500-1519. doi:10.1007/s13346-023-01320-z