Protein degradation is a fundamental biological process that regulates the life cycle of proteins within the cell. It ensures that damaged, misfolded, or unnecessary proteins are broken down and eliminated, maintaining cellular homeostasis and preventing the accumulation of potentially harmful proteins. This process is vital not only for maintaining normal cellular function but also for a wide range of physiological processes, including cell cycle progression, signal transduction, and response to stress.

Protein degradation pathways are sophisticated and tightly regulated, involving multiple enzymes and cellular systems. Among the most prominent pathways are the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and autophagy, two highly conserved mechanisms that mediate the controlled degradation of proteins. In addition, protein degradation has been implicated in several diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative and metabolic disorders, making it an important area of research for drug discovery and therapeutic development.

As experts in protein structure analysis, Creative Biostructure offers comprehensive structural biology services to advance your project, including X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM) Services, and NMR spectroscopy, and more.

Mechanisms of Protein Degradation

Protein degradation in cells occurs by several mechanisms, each involving a different pathway and set of molecular machinery. The two primary pathways involved in regulated protein degradation are the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and autophagy, but there are other lesser-known systems as well.

Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS)

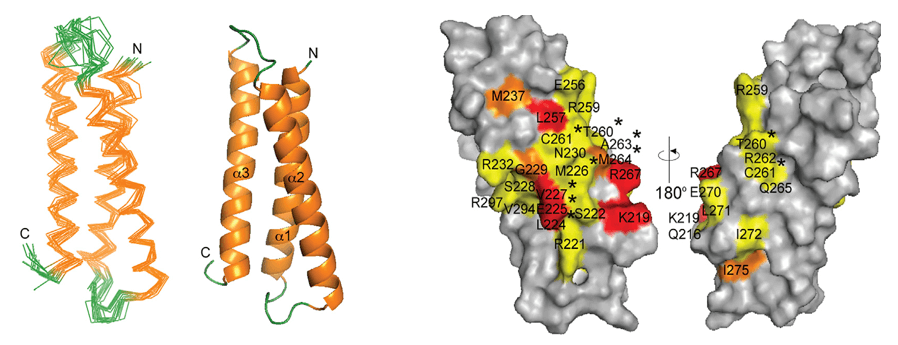

The ubiquitin-proteasome system is the best studied and understood protein degradation pathway. It is responsible for the degradation of the majority of intracellular proteins, including regulatory proteins involved in the cell cycle, apoptosis, and transcription. The UPS functions through a process called ubiquitination, in which proteins are tagged with small molecules called ubiquitin before being targeted for degradation by the proteasome.

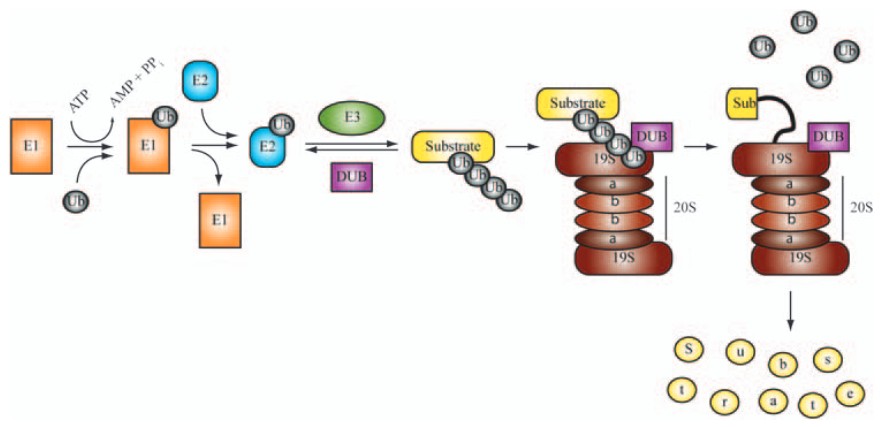

- Ubiquitination: Ubiquitination involves a cascade of reactions mediated by a group of enzymes known as E1 (ubiquitin-activating enzyme), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme), and E3 (ubiquitin ligase). The process begins with the activation of ubiquitin by E1, which then transfers the activated ubiquitin to E2. The E3 ligase, which is highly specific for its target proteins, catalyzes the transfer of ubiquitin from E2 to the target protein. Multiple ubiquitin molecules are added to form a polyubiquitin chain, which serves as a signal for recognition by the proteasome.

- Proteasome: Once polyubiquitinated, the target protein is recognized by the 26S proteasome, a large protease complex consisting of a 20S catalytic core particle and a 19S regulatory particle. The proteasome unfolds the ubiquitinated protein and translocates it into the catalytic core, where it is cleaved into smaller peptides by proteolytic enzymes. The ubiquitin chain is recycled during this process, and the resulting peptides are typically further degraded into amino acids by other cellular proteases or processed into smaller peptides for presentation by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules.

Figure 1. Major enzymatic components of the ubiquitin proteasome pathway (UPS). (Eldridge and O'Brien, 2009)

Figure 1. Major enzymatic components of the ubiquitin proteasome pathway (UPS). (Eldridge and O'Brien, 2009)

The UPS is crucial for maintaining cellular homeostasis and regulating the levels of specific proteins involved in cell signaling, stress responses, and apoptosis. Dysregulation of the UPS has been implicated in a variety of diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and cardiovascular diseases.

Autophagy

Autophagy is a process by which cells degrade and recycle their own components, including proteins, damaged organelles, and other cellular debris. It is essential for cellular survival, particularly under conditions of stress, such as nutrient deprivation, hypoxia, and oxidative damage.

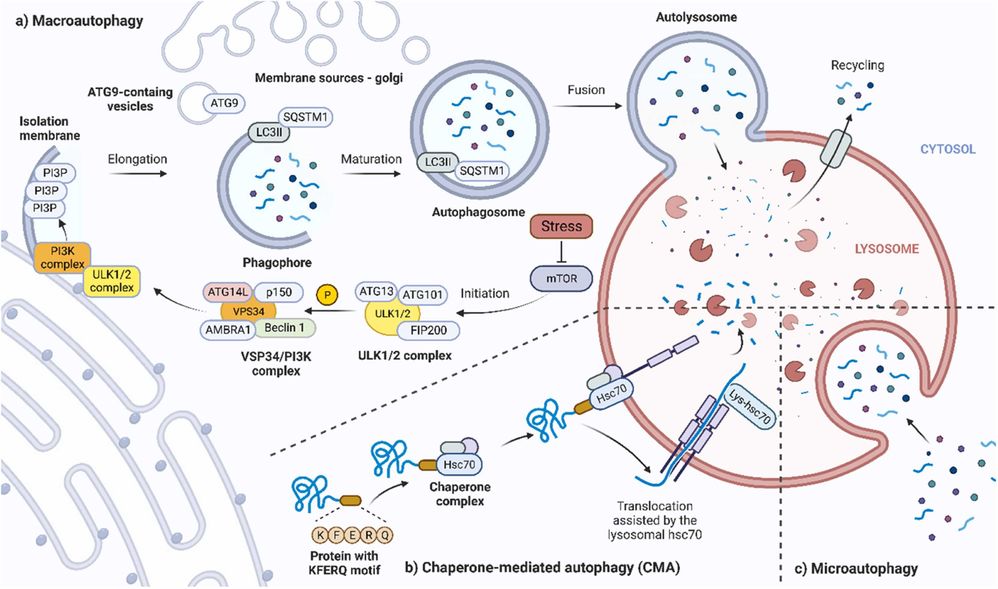

- Macroautophagy: The most common form of autophagy, macroautophagy, involves the formation of a double-membrane vesicle called the autophagosome, which engulfs cellular material destined for degradation. The autophagosome then fuses with a lysosome, where its contents are degraded by lysosomal enzymes. This pathway is particularly important for the degradation of large aggregates of misfolded proteins and damaged organelles.

- Microautophagy and Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy: Other forms of autophagy include microautophagy, in which lysosomes directly engulf small portions of the cytoplasm, and chaperone-mediated autophagy, which involves the selective degradation of specific proteins recognized by chaperones that direct them to the lysosome.

Autophagy is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis, especially during periods of metabolic stress or infection. The autophagic pathway is highly regulated by various signaling networks, such as the mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) pathway, which senses nutrient availability and cellular energy status. Dysregulation of autophagy has been implicated in several diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease, as well as cancer.

Figure 2. Overview of cellular processes leading to three major types of autophagy. A) Macroautophagy. B) Chaperone-mediated autophagy. C) Microautophagy. (Škubník et al., 2023)

Figure 2. Overview of cellular processes leading to three major types of autophagy. A) Macroautophagy. B) Chaperone-mediated autophagy. C) Microautophagy. (Škubník et al., 2023)

Lysosomal Degradation

Lysosomal degradation is another important pathway for protein degradation, particularly in the context of autophagy. The lysosome is an acidic organelle containing numerous hydrolases that degrade proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids. This pathway is primarily responsible for the degradation of macromolecules that have been internalized by endocytosis or phagocytosis or that have been sequestered in autophagic vesicles. Lysosomal degradation is slower than proteasomal degradation, but plays a critical role in maintaining cellular homeostasis, especially for large protein aggregates and damaged organelles.

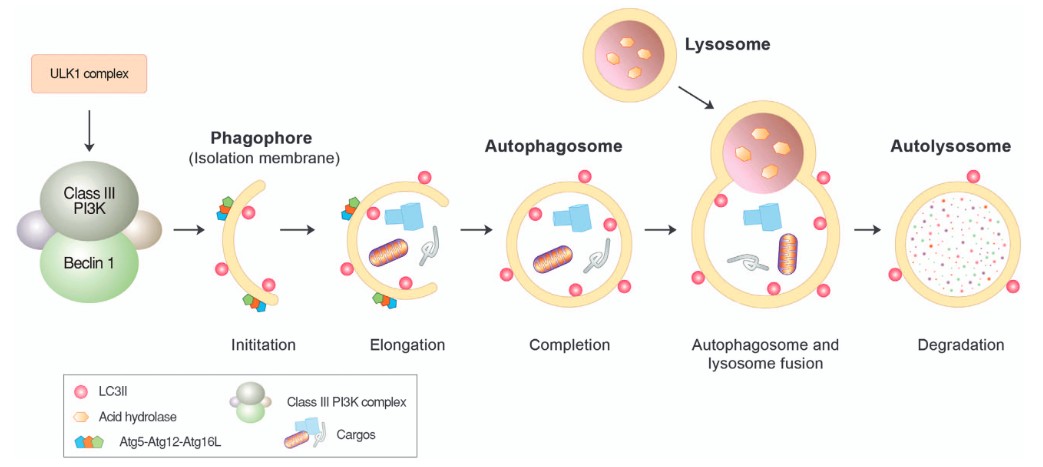

Figure 3. Autophagosome formation and lysosomal degradation. Autophagosome formation can be triggered when the mTOR complex is inhibited by various stressors, such as starvation. This induces the assembly of the ULK protein complex composed of ULK1, Atg13 and FIP200 at the isolation membrane, which, in turn, activates the formation of the Beclin-1/PI3KC3 complex composed of Beclin-1, UVRAG, Bif-1, Ambra1, Vps15 and Vps34. During the elongation of the isolation membrane, the Atg5-Atg12-Atg16L1 complex mediates the conjugation of PE to LC3-I, generating LC3-II that relocates from the cytosol to the autophagic membrane and is anchored on its surface. The resulting autophagic membrane structures—autophagosomes—are fused with lysosomes to form autolysosomes, wherein cargoes, including misfolded proteins, are degraded by lysosomal hydrolases. (Ciechanover and Kwon, 2015)

Figure 3. Autophagosome formation and lysosomal degradation. Autophagosome formation can be triggered when the mTOR complex is inhibited by various stressors, such as starvation. This induces the assembly of the ULK protein complex composed of ULK1, Atg13 and FIP200 at the isolation membrane, which, in turn, activates the formation of the Beclin-1/PI3KC3 complex composed of Beclin-1, UVRAG, Bif-1, Ambra1, Vps15 and Vps34. During the elongation of the isolation membrane, the Atg5-Atg12-Atg16L1 complex mediates the conjugation of PE to LC3-I, generating LC3-II that relocates from the cytosol to the autophagic membrane and is anchored on its surface. The resulting autophagic membrane structures—autophagosomes—are fused with lysosomes to form autolysosomes, wherein cargoes, including misfolded proteins, are degraded by lysosomal hydrolases. (Ciechanover and Kwon, 2015)

Other Pathways: Calpains and SUMOylation

In addition to the UPS and autophagy, there are other less prominent but important pathways involved in protein degradation:

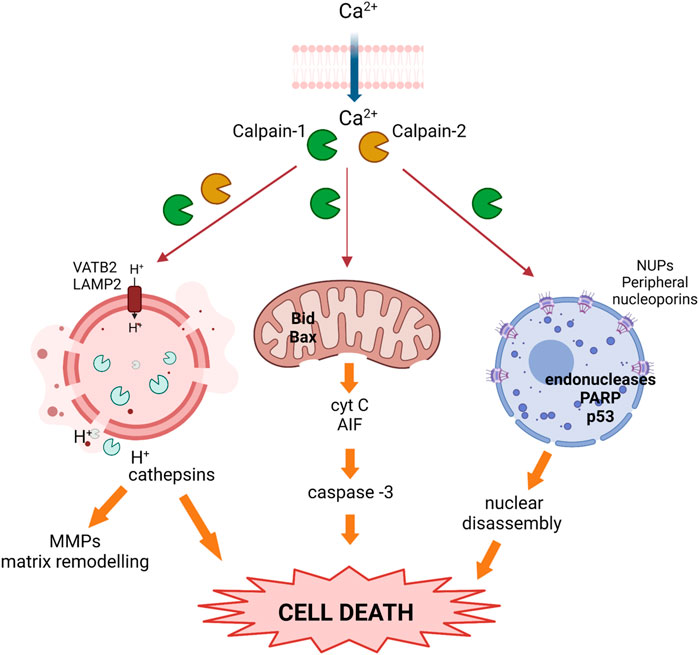

- Calpains: Calpains are a family of calcium-dependent cysteine proteases that mediate the degradation of specific substrate proteins in response to calcium signals. Calpains play important roles in the regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics, cell migration and apoptosis.

Figure 4. Activated calpains trigger cell death during the weaning process. Upon calcium overload, calpains become activated and translocate to different subcellular organelles where they cleave target proteins, inducing nuclear, lysosomal, and mitochondrial membrane destabilization, the release of cathepsins and pro-apoptotic proteins, and prompting cell death. (García-Trevijano et al., 2023)

Figure 4. Activated calpains trigger cell death during the weaning process. Upon calcium overload, calpains become activated and translocate to different subcellular organelles where they cleave target proteins, inducing nuclear, lysosomal, and mitochondrial membrane destabilization, the release of cathepsins and pro-apoptotic proteins, and prompting cell death. (García-Trevijano et al., 2023)

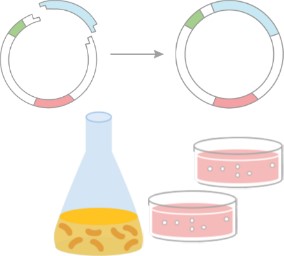

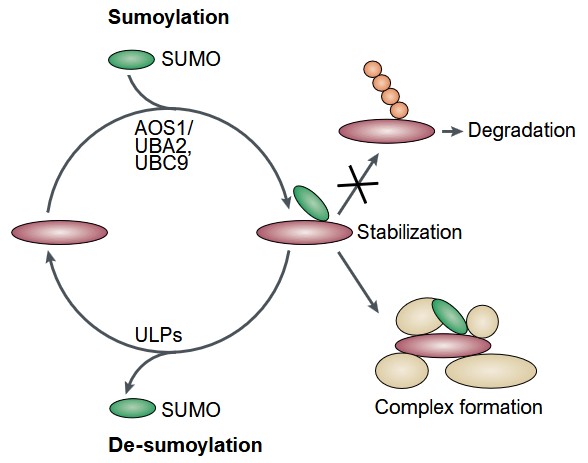

- SUMOylation: SUMOylation is a post-translational modification where small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) proteins are added to target proteins. While SUMOylation typically regulates protein function rather than degradation, it can also tag proteins for degradation by the proteasome.

Figure 5. Reversible modification of proteins by SUMO and its consequences. SUMOylation either prevents ubiquitylation followed by degradation or results in the formation of protein complexes. SUMO is depicted in green, ubiquitin in red. SUMOylation requires AOS1/UBA2 and UBC9 enzymes; de-SUMOylation is catalyzed by members of the ULP family. (Müller et al., 2001)

Figure 5. Reversible modification of proteins by SUMO and its consequences. SUMOylation either prevents ubiquitylation followed by degradation or results in the formation of protein complexes. SUMO is depicted in green, ubiquitin in red. SUMOylation requires AOS1/UBA2 and UBC9 enzymes; de-SUMOylation is catalyzed by members of the ULP family. (Müller et al., 2001)

Importance of Protein Degradation

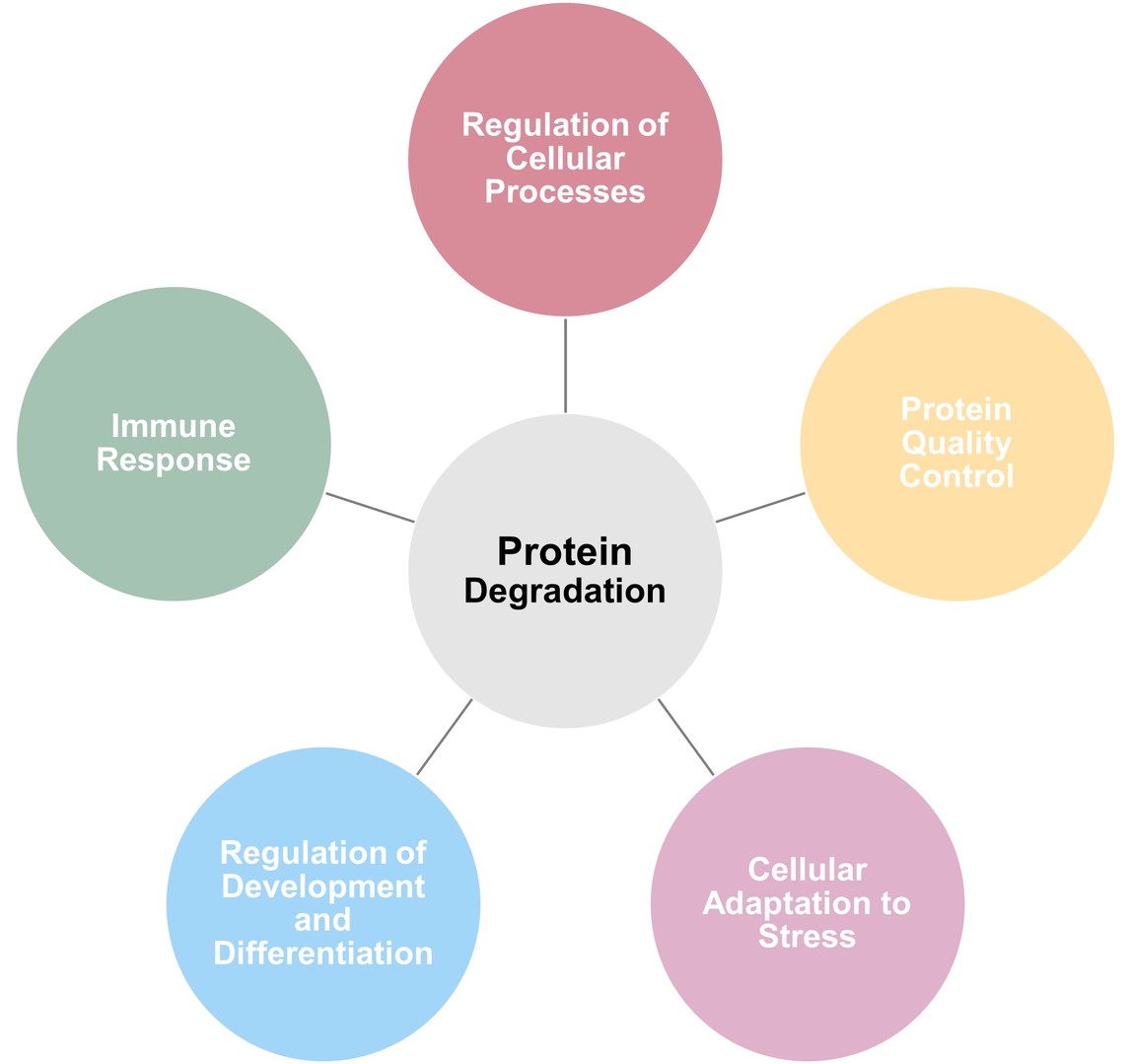

Protein degradation is essential for a variety of cellular processes, including:

- Regulation of Cellular Processes: Protein degradation ensures that proteins are degraded at the appropriate time and prevents the accumulation of unwanted or damaged proteins. This regulation is critical for maintaining the balance of key cellular functions, including signal transduction, gene expression, and cell division.

- Protein Quality Control: Cells constantly produce misfolded or damaged proteins due to various factors such as oxidative stress, mutations, or errors in protein synthesis. Protein degradation pathways, such as the UPS and autophagy, play a critical role in preventing the accumulation of these misfolded proteins, which can form toxic aggregates and contribute to diseases such as neurodegeneration.

- Cellular Adaptation to Stress: In response to environmental stressors such as nutrient deprivation, oxidative stress, or hypoxia, cells activate protein degradation pathways to maintain cellular homeostasis and ensure survival. This includes the degradation of damaged proteins, as well as the recycling of cellular components to support energy production and stress adaptation.

- Regulation of Development and Differentiation: Protein degradation is essential during development and differentiation processes. For example, the degradation of certain regulatory proteins is necessary for the progression of the cell cycle, tissue remodeling, and the maintenance of stem cell populations.

- Immune Response: The UPS plays an important role in the regulation of immune responses by degrading proteins involved in immune signaling, antigen processing, and regulation of immune cell activation.

Figure 6. Physiological roles of protein degradation.

Figure 6. Physiological roles of protein degradation.

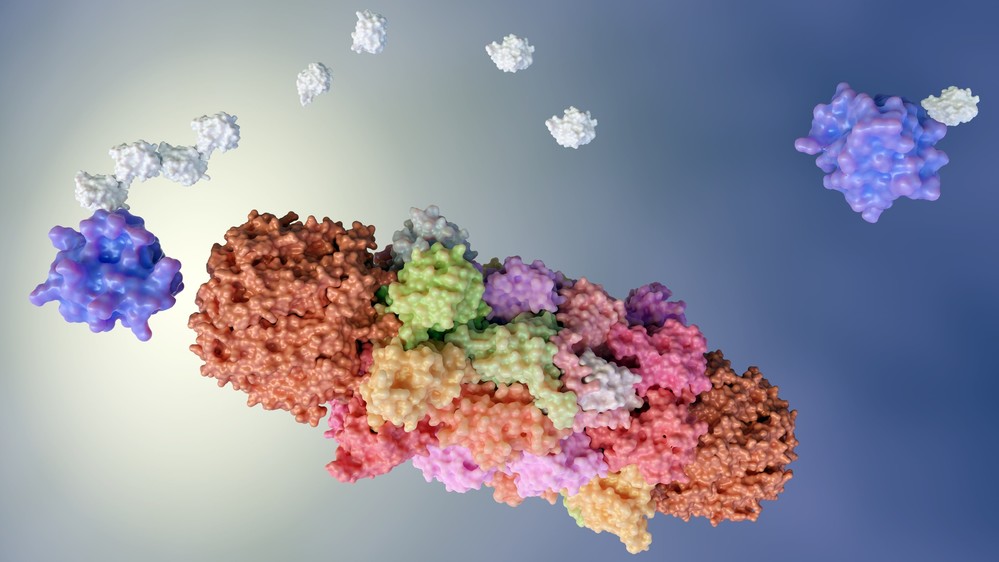

Protein Degradation-Based Therapy Strategies

The development of protein degradation-based therapies has emerged as a groundbreaking approach in modern medicine, offering new ways to treat diseases previously considered untreatable. These therapies use the cell's natural protein degradation mechanisms - primarily the proteasome and lysosome - to selectively target and degrade disease-causing proteins, including those that drive cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and other complex diseases. By exploiting targeted protein degradation, scientists are developing drugs that can remove harmful proteins rather than simply inhibiting them.

Key strategies in protein degradation-based therapies include PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras), molecular glues, LYTACs (Lysosome-Targeting Chimeras), and other innovative approaches.

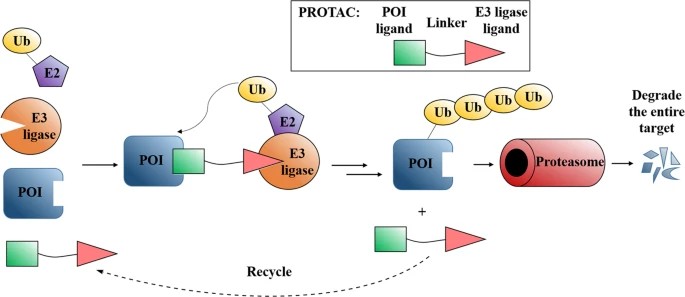

PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras)

PROTACs are one of the most well-known and widely studied approaches in the field of targeted protein degradation. They are bifunctional molecules that can recruit an E3 ligase enzyme to a specific target protein, thereby tagging it for degradation by the proteasome. The name "PROTAC" is derived from the fact that these compounds induce proteolysis of a target protein via the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS).

PROTACs consist of three key components:

- Targeting moiety: A ligand that specifically binds to the protein of interest.

- Linker: A flexible molecule that connects the two functional parts of the PROTAC.

- E3 ligase ligand: A small molecule that recruits an E3 ligase to the target protein.

When PROTAC binds to its target protein, it forms a ternary complex with the E3 ligase that catalyzes the attachment of ubiquitin to the target protein. This ubiquitination signals the target protein for recognition and degradation by the proteasome.

Figure 7. Mode of action of PROTACs. (Sun et al., 2019)

Figure 7. Mode of action of PROTACs. (Sun et al., 2019)

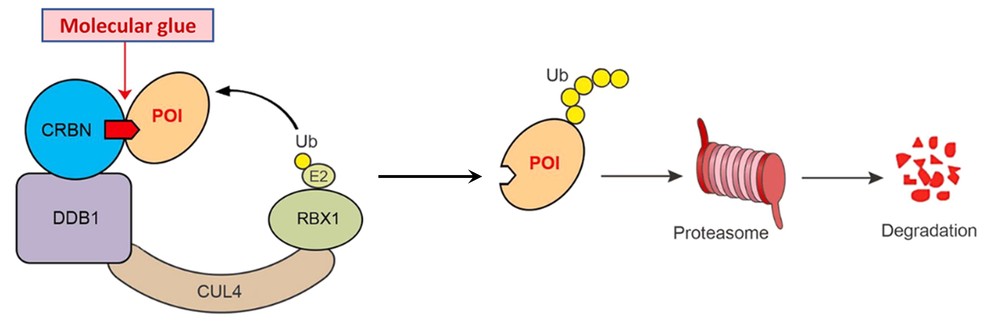

Molecular Glues

Molecular glues are small molecules that promote the induced proximity between a target protein and an E3 ligase, leading to the ubiquitination and degradation of the target protein by the proteasome. Unlike PROTACs, molecular glues do not require a linker to bind both the target protein and the E3 ligase; instead, they rely on molecular recognition to bring the two proteins together in close proximity.

Molecular glues work by binding to a specific site on the target protein, inducing a conformational change that allows the protein to interact with an E3 ligase. The E3 ligase then ubiquitinates the target protein, marking it for degradation. Molecular glues often exploit protein-protein interactions to facilitate the degradation process, making them different from traditional small molecule inhibitors.

Figure 8. Schematic presentation of the degradation of a protein of interest (POI) via the ubiquitin (Ub)−proteasome system using a molecular glue. (Adapted from Sasso et al., 2023)

Figure 8. Schematic presentation of the degradation of a protein of interest (POI) via the ubiquitin (Ub)−proteasome system using a molecular glue. (Adapted from Sasso et al., 2023)

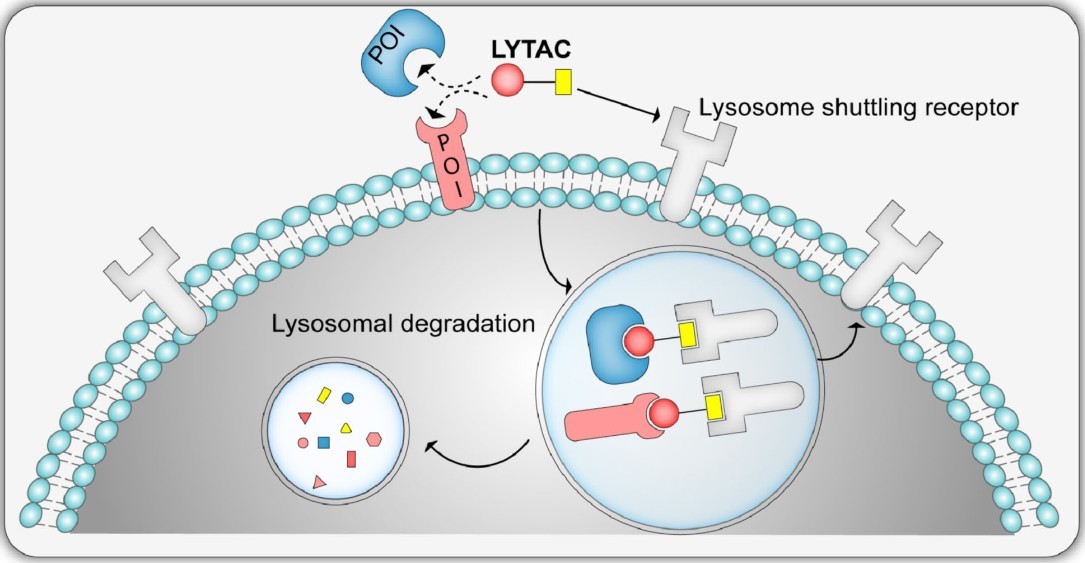

LYTACs (Lysosome-Targeting Chimeras)

LYTACs are a new class of bifunctional molecules similar to PROTACs, but instead of recruiting an E3 ligase to target proteins for degradation by the proteasome, LYTACs direct proteins to the lysosome for degradation. This system harnesses the cell's natural autophagic machinery, which is responsible for the degradation of large aggregates, damaged organelles and unwanted proteins.

LYTACs consist of a ligand that targets the protein of interest and another ligand that binds to ligand receptors on the cell surface, such as asialoglycoprotein receptors (ASGPR) or macropinocytosis receptors. After binding to the target protein and the receptor, the LYTAC-protein complex is internalized into the cell, where it is delivered to the lysosome for degradation.

The lysosome is capable of degrading a wide variety of substrates, including misfolded proteins, aggregates, and damaged organelles, making it an ideal pathway for targeted degradation. LYTACs allow for the selective removal of specific proteins while avoiding off-target effects commonly associated with proteasomal degradation.

Figure 9. Schematic representation of the LYTAC system, showing internalization and degradation of extracellular/membrane‐bound protein (POI) by the lysosome shuttling receptors. (Ramadas et al., 2021)

Figure 9. Schematic representation of the LYTAC system, showing internalization and degradation of extracellular/membrane‐bound protein (POI) by the lysosome shuttling receptors. (Ramadas et al., 2021)

Other Targeted Degradation Strategies

In addition to PROTACs, molecular adhesives and LYTACs, there are several other innovative strategies for targeted protein degradation, some of which are still in the early stages of research.

- AUTOTACs (Autophagy-Taking Chimeras): AUTOTACs are a newer generation of targeted degradation molecules that engage the autophagic machinery to degrade specific proteins. Similar to LYTACs, AUTOTACs facilitate the recognition and degradation of target proteins through autophagy, a process involving autophagosomes and lysosomal degradation. This strategy is particularly useful for degrading larger proteins or aggregates that are not easily degraded by the proteasome.

- PROTAC-like Peptoids: Peptoids are synthetic analogs of peptides with increased stability and improved cell permeability. PROTAC-like peptoids are being developed to selectively target proteins for degradation. These compounds combine the degradation capabilities of PROTACs with the advantages of peptoid chemistry, including improved stability and reduced immunogenicity.

- Proteasome-Independent Targeting: Some novel approaches aim to degrade proteins via proteasome-independent pathways. These strategies use molecular chaperones or small molecules that can destabilize the protein, causing it to be degraded by mechanisms other than the proteasome, such as lysosomal degradation or endosomal sorting pathways.

Therapeutic Applications

Given the importance of protein degradation in regulating cellular functions, its dysregulation is often associated with disease. Understanding protein degradation pathways has significant therapeutic implications in several areas:

Cancer Therapy

Cancer cells often hijack protein degradation pathways to enhance their survival, proliferation and resistance to apoptosis. For example, many cancer cells have altered UPS activity leading to the stabilization of oncogenic proteins such as cyclins and survival factors. Targeting the UPS and promoting the degradation of these oncogenic proteins may be a promising therapeutic strategy. PROTACs are currently being investigated as potential therapies for cancer and other diseases.

Neurodegenerative Diseases

Neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and Huntington's disease are characterized by the accumulation of misfolded proteins and protein aggregates. These aggregates disrupt normal cellular function and lead to neuronal death. Enhancing protein degradation pathways, particularly autophagy and the UPS, is being explored as a therapeutic strategy to remove toxic protein aggregates and slow disease progression.

Inflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases

In diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the dysregulation of protein degradation contributes to chronic inflammation and tissue damage. Targeting specific components of the protein degradation pathways may offer novel approaches for managing inflammation and immune responses in these diseases.

Metabolic Disorders

Metabolic diseases such as diabetes and obesity are associated with defects in the regulation of protein degradation pathways. In these diseases, dysfunctional protein degradation can lead to insulin resistance, lipid accumulation, and impaired metabolic homeostasis. By modulating protein degradation pathways, it may be possible to restore normal metabolic function and improve disease outcomes.

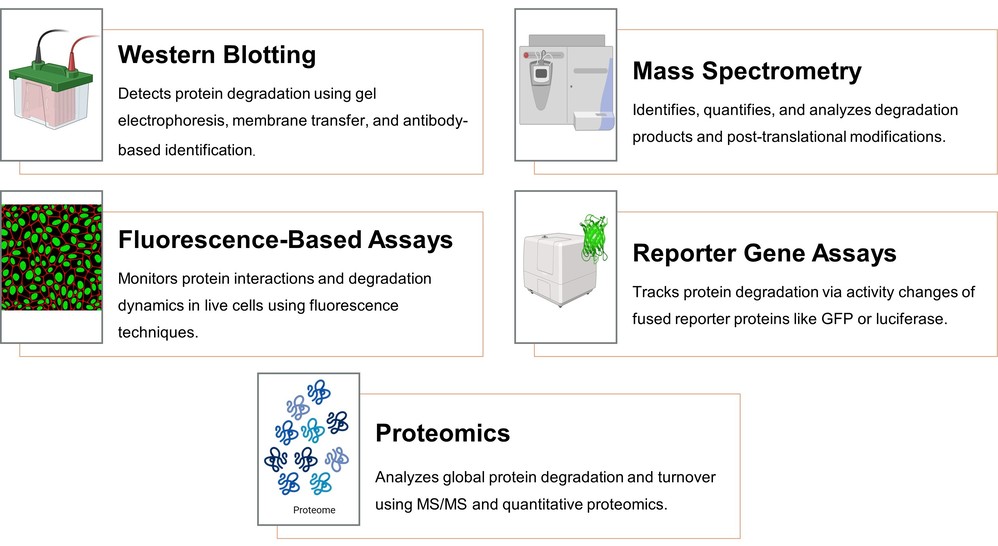

Analytical Techniques in Protein Degradation Studies

To study protein degradation and understand the underlying mechanisms, researchers rely on various analytical techniques. These techniques allow for the identification, quantification, and analysis of proteins targeted for degradation.

Western Blotting

Western blotting is one of the most commonly used techniques for studying protein degradation. It involves separating proteins by size using gel electrophoresis, transferring them to a membrane, and detecting specific proteins using antibodies. Western blotting can be used to monitor protein degradation over time, identify ubiquitinated proteins, and assess changes in proteasome activity.

Mass Spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) is a powerful technique for studying protein degradation on a global scale. MS can identify and quantify proteins, detect post-translational modifications such as ubiquitination, and determine the structure of protein degradation products. MS is often used in proteomics studies to investigate the dynamics of protein turnover and degradation in cells.

Fluorescence-Based Assays

Fluorescence-based assays, such as fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) or fluorescence polarization, are used to monitor protein-protein interactions, including those involved in protein degradation. These assays can be used to study the dynamics of proteasomal or autophagic degradation in live cells.

Reporter Gene Assays

Reporter gene assays use a reporter protein, such as GFP (green fluorescent protein) or luciferase, fused to the protein of interest. The degradation of the target protein can be monitored by measuring the reporter activity over time. This method is particularly useful for studying protein turnover and degradation under different experimental conditions.

Proteomics

Proteomic approaches, including tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) and quantitative proteomics, allow for the global analysis of protein degradation and turnover. These techniques can identify the full complement of proteins undergoing degradation and provide insights into the specific components of the degradation machinery involved in different pathways.

Figure 10. Analytical techniques in protein degradation studies.

Figure 10. Analytical techniques in protein degradation studies.

Select Service

Related Reading

As a leading provider of structural biology analysis services, Creative Biostructure offers a comprehensive range of protein-related solutions, including identification, characterization, and quantification. Our advanced technologies and expertise enable precise analysis to support research and development in various fields. Contact our experts today for personalized consultation and tailored solutions.

References

- Ciechanover A, Kwon YT. Degradation of misfolded proteins in neurodegenerative diseases: therapeutic targets and strategies. Exp Mol Med. 2015;47(3):e147-e147. doi:10.1038/emm.2014.117

- Eldridge AG, O'Brien T. Therapeutic strategies within the ubiquitin proteasome system. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17(1):4-13. doi:10.1038/cdd.2009.82

- García-Trevijano ER, Ortiz-Zapater E, Gimeno A, Viña JR, Zaragozá R. Calpains, the proteases of two faces controlling the epithelial homeostasis in mammary gland. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;11:1249317. doi:10.3389/fcell.2023.1249317

- Nie M, Boddy M. Cooperativity of the sumo and ubiquitin pathways in genome stability. Biomolecules. 2016;6(1):14. doi:10.3390/biom6010014

- Müller S, Hoege C, Pyrowolakis G, Jentsch S. Sumo, ubiquitin's mysterious cousin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(3):202-210. doi:10.1038/35056591

- Ramadas B, Kumar Pain P, Manna D. LYTACs: an emerging tool for the degradation of non‐cytosolic proteins. ChemMedChem. 2021;16(19):2951-2953. doi:10.1002/cmdc.202100393

- Sasso JM, Tenchov R, Wang D, Johnson LS, Wang X, Zhou QA. Molecular glues: the adhesive connecting targeted protein degradation to the clinic. Biochemistry. 2023;62(3):601-623. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.2c00245

- Škubník J, Svobodová Pavlíčková V, Ruml T, Rimpelová S. Autophagy in cancer resistance to paclitaxel: Development of combination strategies. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2023;161:114458. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114458

- Sun X, Gao H, Yang Y, et al. PROTACs: great opportunities for academia and industry. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2019;4(1):64. doi:10.1038/s41392-019-0101-6

- Zhao L, Zhao J, Zhong K, Tong A, Jia D. Targeted protein degradation: mechanisms, strategies and application. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):113. doi:10.1038/s41392-022-00966-4