Microarray analysis techniques have revolutionized the field of molecular biology by enabling high-throughput analysis of gene expression, gene identification, and molecular profiling of disease. These technologies enable researchers to study thousands of genes simultaneously, providing comprehensive insights into the complex mechanisms underlying biological systems. Since the development of the first DNA microarrays in the 1990s, the field has grown exponentially, with applications ranging from basic molecular research to clinical diagnostics and personalized medicine. The ability to perform large-scale, parallel analysis of DNA, RNA, and proteins has made microarrays indispensable for studying gene function, gene regulation, and protein interactions.

Discover the microarray analysis techniques with Creative Biostructure, where we provide comprehensive insight into cutting-edge methodologies for high-throughput gene expression profiling, genotyping and biomarker discovery.

Types of Microarrays

Microarrays come in a variety of forms, depending on the type of biomolecule being studied. The most common microarrays are DNA- and RNA-based, but advances in technology have led to the development of protein arrays and other specialized types. In this section, we will discuss the different categories of microarrays, their unique characteristics, and their specific applications.

DNA Microarrays

DNA microarrays, also known as gene chips, are the most widely used type of microarray. These arrays consist of thousands of short DNA probes (oligonucleotides or cDNA) immobilized on a solid surface, such as a glass slide or silicon chip. The probes are designed to represent different genes or specific genomic regions.

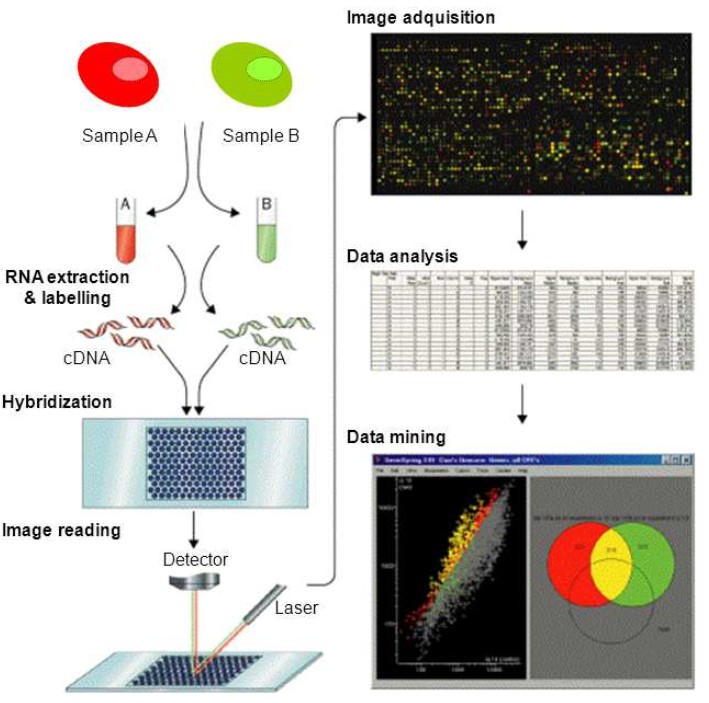

In a typical DNA microarray experiment, RNA is extracted from a sample, reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA), and then hybridized to the array. The hybridization process involves the binding of cDNA to complementary probes on the array. After washing away unbound material, the remaining signal is quantified, providing a measure of the abundance of specific gene expression in the sample.

Applications of DNA microarrays include gene expression profiling, comparative genomics, and the identification of genetic variations, such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and gene mutations.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the DNA microarray methodology. DNA microarrays are commonly used to detect messenger RNAs (mRNA), referred to as expression profiling. The method consists in the fluorescently labelling of RNA while the RNA is converted into complementary DNA (cDNA). Amplification of sequences by PCR is sometimes incorporated into this step. Two-color labeling allows two samples or conditions, to be hybridized to the same array and their gene expression profiles compared via the difference in the fluorescence of the two samples. Statistical post-processing of the fluorescence data is usually necessary to eliminate artifacts and false results from the data obtained. (Ramn et al., 2012)

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the DNA microarray methodology. DNA microarrays are commonly used to detect messenger RNAs (mRNA), referred to as expression profiling. The method consists in the fluorescently labelling of RNA while the RNA is converted into complementary DNA (cDNA). Amplification of sequences by PCR is sometimes incorporated into this step. Two-color labeling allows two samples or conditions, to be hybridized to the same array and their gene expression profiles compared via the difference in the fluorescence of the two samples. Statistical post-processing of the fluorescence data is usually necessary to eliminate artifacts and false results from the data obtained. (Ramn et al., 2012)

RNA Microarrays

RNA microarrays are similar to DNA microarrays but are specifically designed to study RNA molecules. They are used to analyze gene expression at the transcript level. RNA microarrays use complementary RNA (cRNA) probes to detect the presence of specific RNA sequences in the sample. By comparing the expression levels of specific genes across different samples or conditions, RNA microarrays enable researchers to uncover regulatory networks and signaling pathways.

RNA microarrays have been used extensively in transcriptomics, including differential gene expression studies, biomarker discovery, and understanding of disease mechanisms.

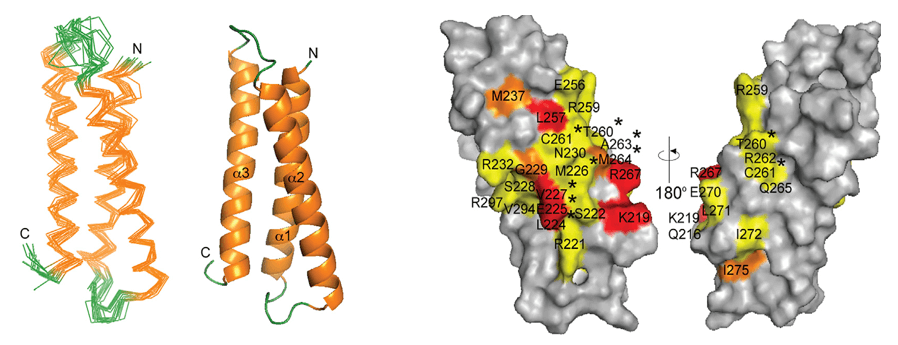

Protein Microarrays

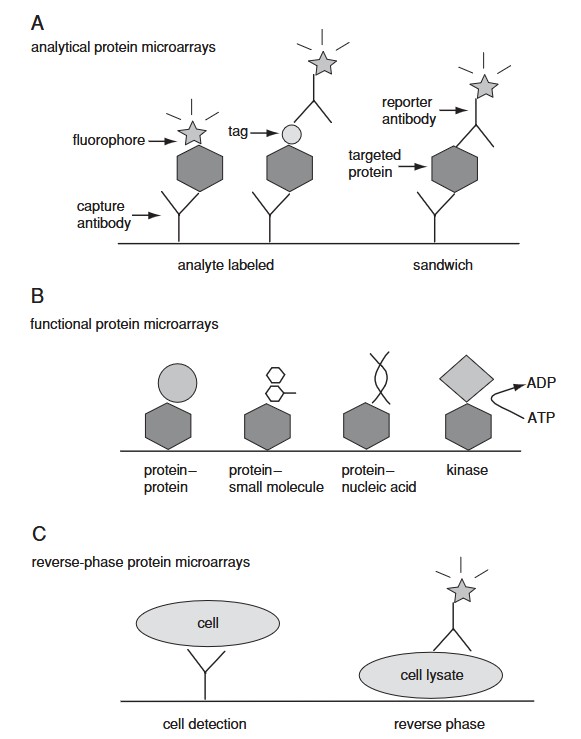

Protein microarrays are a relatively recent innovation that enable the high-throughput study of proteins, their interactions and functions. These arrays typically consist of immobilized proteins (such as enzymes, antibodies, or antigens) on a solid surface. They can be used for a variety of applications, including detecting protein-protein interactions, screening for binding partners, and measuring the activity of enzymes.

Protein microarrays have found applications in proteomics, drug discovery, diagnostics, and therapeutic antibody development.

Figure 2. Three categories of protein microarrays. (A) Analytical protein microarrays are mostly represented by antibody arrays and focus on protein detection. In this class of microarrays, targeted proteins can be detected either by direct labeling or using a reporter antibody in sandwich assay format. (B) Functional protein microarrays have broad applications in studying protein interactions, including protein binding and enzyme-substrate reactions. (C) Reverse-phase protein microarrays provide a different array format by immobilizing many different lysate samples on the same chip. (Sutandy et al., 2013)

Figure 2. Three categories of protein microarrays. (A) Analytical protein microarrays are mostly represented by antibody arrays and focus on protein detection. In this class of microarrays, targeted proteins can be detected either by direct labeling or using a reporter antibody in sandwich assay format. (B) Functional protein microarrays have broad applications in studying protein interactions, including protein binding and enzyme-substrate reactions. (C) Reverse-phase protein microarrays provide a different array format by immobilizing many different lysate samples on the same chip. (Sutandy et al., 2013)

Specialized Microarrays

Beyond DNA, RNA, and protein microarrays, several specialized arrays have been developed. These include tissue microarrays (which allow the study of multiple tissue samples on a single slide) and antibody microarrays (used to detect specific proteins or antibodies in complex biological samples).

These specialized arrays offer unique advantages, such as the ability to study disease tissues on a large scale or to profile immune responses in different individuals.

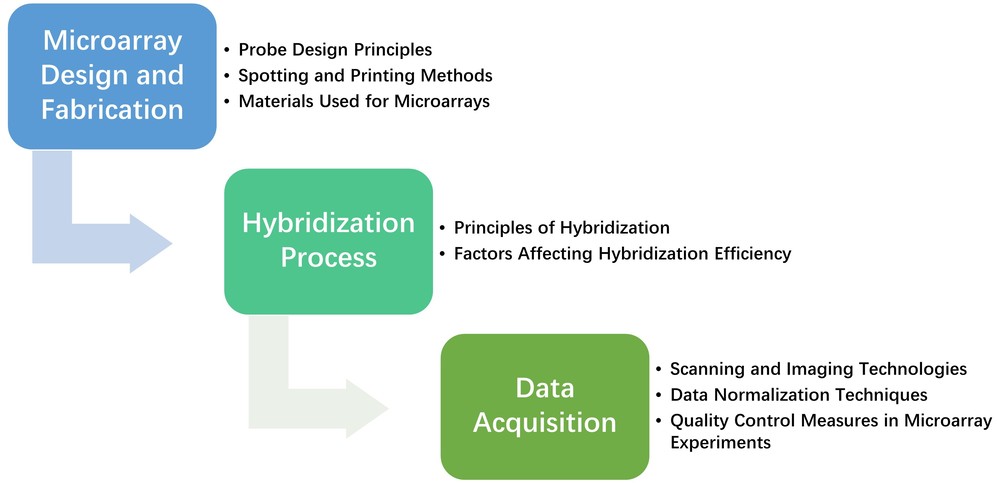

Microarray Design and Fabrication

Probe Design Principles

The choice of probes is fundamental to the success of a microarray experiment. Probes should be specific for the target molecule to ensure that they bind only to the intended sequences. For DNA and RNA microarrays, probes are typically short oligonucleotides (20-70 nucleotides long) or complementary DNA (cDNA) fragments. The length of the probe is a critical factor in its specificity, as longer probes tend to be more specific, but shorter probes are more efficient at hybridization.

Probe design also needs to take into account the GC content, melting temperature (Tm), and secondary structure of the probes to ensure optimal hybridization conditions.

Spotting and Printing Methods

Microarrays are typically made by depositing individual DNA, RNA, or protein probes onto a solid surface. There are several methods for depositing probes, including microarray printing, inkjet printing, and photolithography. The method used depends on the type of array being produced, the material of the surface, and the precision required.

For DNA and RNA arrays, microarray printing is the most commonly used method. In this process, tiny droplets of the probe solution are deposited onto a solid surface in a highly controlled manner, creating a grid of probe spots.

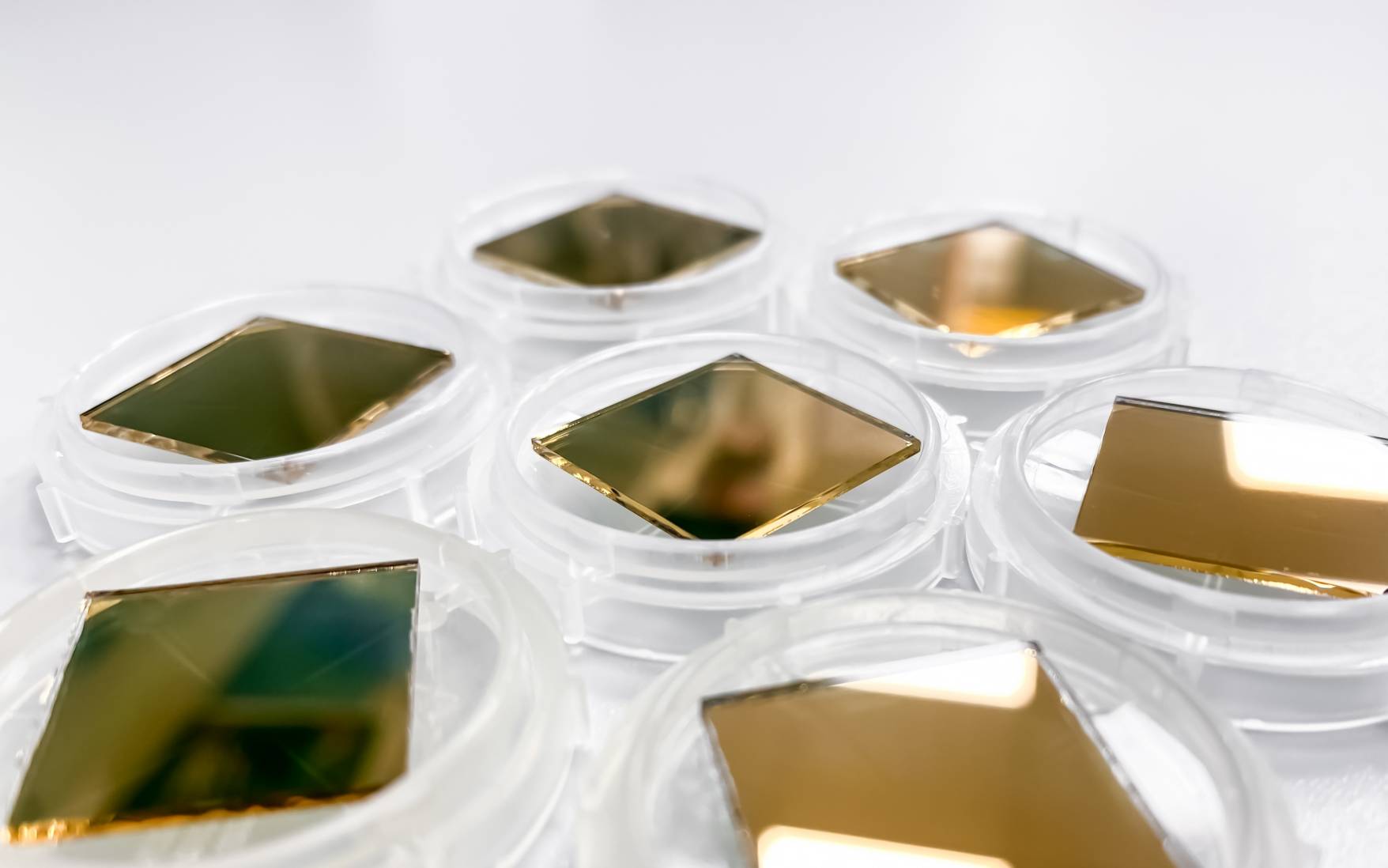

Materials Used for Microarrays

Microarrays are typically fabricated on solid surfaces, such as glass slides, silicon chips, or membrane-based materials. The choice of substrate material is critical to the performance of the array, as it affects the binding efficiency, stability, and reproducibility of the array. Glass is the most commonly used material for DNA and RNA microarrays, while silicon chips are often used for more specialized applications.

Surface modifications, such as the use of poly-L-lysine or aminosilane coatings, can be used to improve the attachment of probes to the solid surface.

Hybridization Process

Hybridization is a key step in the microarray experiment as it allows the probes on the array to interact with the target molecules in the sample. In this section, we will explore the principles of hybridization and the factors that influence its efficiency.

Principles of Hybridization

The hybridization process relies on the complementary base pairing between the probe and target molecules. For DNA and RNA microarrays, the target is typically labeled with a fluorescent dye, while the probes on the array are immobilized on a solid surface. During the hybridization step, the target binds to the complementary probes, and the degree of hybridization can be measured by detecting the fluorescent signal.

Factors Affecting Hybridization Efficiency

Several factors can affect the efficiency of hybridization, including temperature, ionic strength, and probe concentration. Optimal hybridization conditions must be determined experimentally, as the conditions for efficient binding can vary depending on the specific targets and probes being used.

Data Acquisition

Scanning and Imaging Technologies

Microarray scanning and imaging technologies play a critical role in the acquisition of high-resolution data. After hybridization, microarray slides are scanned using laser-based fluorescence scanners that detect signal intensities from fluorescently labeled probes. Commonly used scanning systems include laser-induced fluorescence scanners and charge-coupled device (CCD)-based imaging systems. These scanners capture high-resolution images that allow quantitative measurement of hybridized biomolecules. The resulting fluorescence intensity is directly proportional to the amount of target sequences in the sample.

Data Normalization Techniques

Normalization is a critical step in microarray data analysis to correct for systematic bias and ensure comparability across arrays. Common normalization methods include:

- Global Normalization: Adjusts fluorescence intensities based on a global scaling factor.

- Quantile Normalization: Ensures that the distribution of intensity values is identical across arrays.

- Loess Normalization: A non-linear method that corrects for intensity-dependent biases.

- Median Normalization: Aligns the median intensities of different arrays.

Proper normalization increases the reliability of downstream analyses and allows meaningful comparisons between experimental conditions.

Quality Control Measures in Microarray Experiments

Quality control (QC) ensures the reliability and reproducibility of microarray data. QC measures include:

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) Assessment: Ensures adequate fluorescence intensity.

- Examination of Background Noise: Identifies artifacts and contaminants.

- Evaluation of Replicate Consistency: Confirms the reproducibility of the hybridization.

- Use of Spike-in and Housekeeping Controls: Validates the efficiency of labeling and hybridization.

Figure 3. General microarray workflow.

Figure 3. General microarray workflow.

Applications of Microarray Technology

Gene Expression Profiling

Microarray technology is widely used for large-scale gene expression analysis, allowing researchers to study how genes are upregulated or downregulated in different biological conditions. By comparing gene expression patterns in different cell types, tissues, or disease states, scientists can identify critical regulatory networks, study cellular responses to stimuli, and gain insight into fundamental biological processes. In medical research, microarrays are instrumental in understanding the molecular mechanisms of diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and neurodegenerative disorders. They also serve as a valuable tool in drug discovery, revealing how potential therapeutics affect gene expression profiles and aiding in the identification of new drug targets.

Comparative Genomics and Transcriptomics

Microarrays play a critical role in comparative genomics by facilitating genome-wide analyses across species. This allows researchers to identify conserved and divergent genetic elements, helping to elucidate evolutionary relationships and adaptive mechanisms. In transcriptomics, microarrays allow the comparison of gene expression patterns between species, tissues, or developmental stages, providing insights into gene function and regulation. In addition, microarray-based genome-wide association studies (GWAS) help identify genetic variations associated with traits or diseases, contributing to precision medicine and functional annotation of genes.

Disease Diagnostics and Biomarker Discovery

Microarray technology has revolutionized disease diagnosis by enabling the identification of gene expression signatures associated with various diseases. In oncology, microarrays can differentiate between different cancer subtypes by analyzing tumor-specific gene expression patterns, allowing for accurate classification and prognosis. They also contribute to the discovery of biomarkers for early detection and monitoring of diseases such as autoimmune, cardiovascular, and infectious diseases. By integrating microarray data with other omics approaches, researchers can develop diagnostic tests that improve patient outcomes through more targeted and timely interventions.

Personalized Medicine

Microarrays have significantly advanced personalized medicine by enabling the analysis of patient-specific gene expression profiles. This technology enables clinicians to tailor treatment plans based on an individual's genetic makeup, optimizing therapeutic strategies for better efficacy and minimal side effects. In oncology, microarrays help identify tumor-specific mutations and expression patterns that guide the selection of targeted therapies. Similarly, in pharmacogenomics, microarray-based studies help determine how genetic variations affect drug metabolism and response, leading to more effective and safer drug prescriptions. As personalized medicine continues to evolve, microarrays remain a fundamental tool in precision medicine.

Toxicology and Environmental Monitoring

Microarrays are widely used in toxicology and environmental monitoring to assess the biological effects of pollutants and hazardous substances. By analyzing gene expression changes in response to chemical exposure, microarrays help identify toxicity pathways and predict potential health risks associated with environmental contaminants. They also aid in evaluating the effects of pharmaceuticals, pesticides, heavy metals, and industrial chemicals on biological systems. In ecotoxicology, microarrays contribute to biodiversity conservation by monitoring the genetic responses of wildlife and microbial communities to environmental stressors, providing essential data for environmental risk assessment and regulatory decision-making.

Recent Advances and Future Directions

- Advances in Microarray Design and Fabrication: Innovations such as three-dimensional microarrays and nanoparticle-based probes have improved hybridization efficiency and detection sensitivity.

- Integration with Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Technologies: Combining microarrays with NGS improves data resolution, enabling more comprehensive genomic and transcriptomic analyses.

- New Applications and Emerging Technologies: Emerging applications include microarrays for microbiome profiling, food safety testing, and synthetic biology research.

- Single-Cell Microarray Techniques: Recent developments in single-cell microarrays enable gene expression analysis at the individual cell level, providing insights into cellular heterogeneity and disease mechanisms.

- Microarrays in Precision Medicine: Microarrays contribute to precision medicine by tailoring treatments based on patient-specific genetic profiles, improving drug efficacy and reducing side effects.

Case Study

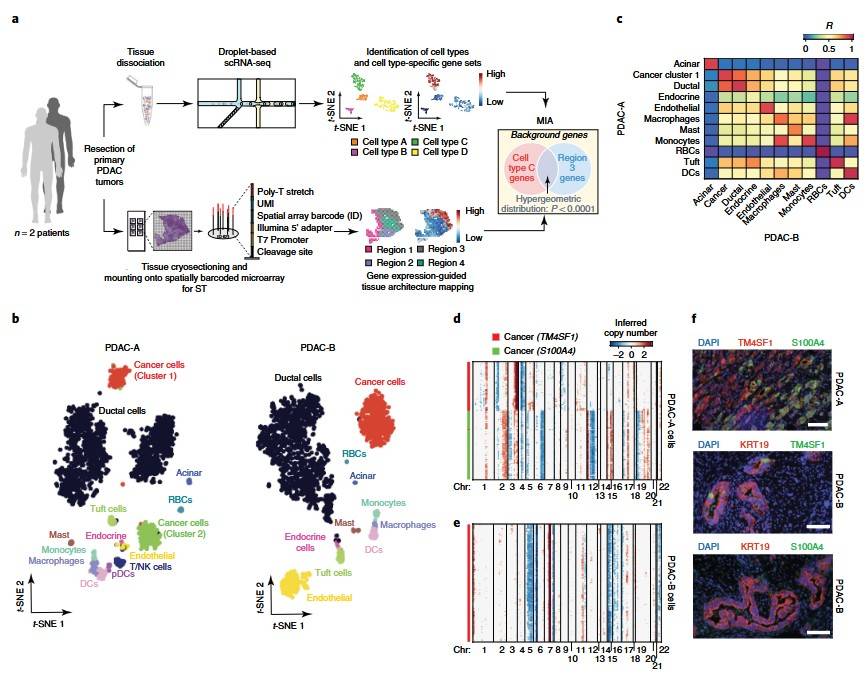

Case 1: Integrating Microarray-Based Spatial Transcriptomics and Single-Cell RNA-Seq Reveals Tissue Architecture in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinomas

This study integrates microarray-based spatial transcriptomics with single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to map gene expression patterns while preserving spatial context. Using a multimodal intersection analysis, the method identifies the precise cellular composition of tissue regions. Applied to pancreatic tumors, it reveals spatially restricted subpopulations of ductal cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and cancer cells, along with their coenrichments. Notably, inflammatory fibroblasts colocalize with cancer cells expressing stress-response genes. This approach provides a powerful tool for uncovering cellular interactions within complex tissues.

Figure 4. scRNA-seq analysis of two tumors from patients with PDAC. (Moncada et al., 2020)

Figure 4. scRNA-seq analysis of two tumors from patients with PDAC. (Moncada et al., 2020)

Case 2: Design and Validation of a DNA-Microarray for Phylogenetic Analysis of Bacterial Communities in Different Oral Samples and Dental Implants

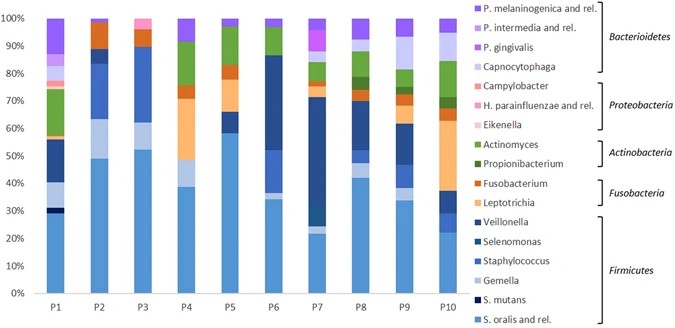

This study presents OralArray, a newly designed and validated phylogenetic DNA microarray for the characterization of oral microbiota. Using Ligation Detection Reaction technology with Universal Arrays (LDR-UA), OralArray targets 22 bacterial groups across six major phyla. It demonstrates high specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility. When tested on oral samples from 10 healthy individuals, the tool identified subject-specific microbial signatures. It was also used to evaluate the efficacy of a disinfectant treatment on healing caps. The OralArray provides a reliable method for studying oral microbiota and monitoring therapeutic effects.

Figure 5. Relative abundance of bacterial targets detected by the OralArray, grouped for individual. For each individual (P1-P10), fluorescence intensities of saliva, lingual plaque, supragingival plaque, and healing cap were grouped and average relative contributions were calculated as percentage of the total fluorescence intensity. (Parolin et al., 2017)

Figure 5. Relative abundance of bacterial targets detected by the OralArray, grouped for individual. For each individual (P1-P10), fluorescence intensities of saliva, lingual plaque, supragingival plaque, and healing cap were grouped and average relative contributions were calculated as percentage of the total fluorescence intensity. (Parolin et al., 2017)

In summary, microarray technology has significantly advanced molecular biology, enabling high-throughput gene and protein expression analysis. Despite challenges related to technical limitations and data interpretation, continuous improvements in design, integration with next-generation sequencing, and novel applications ensure that microarrays remain a vital tool in genomics, disease diagnostics, and personalized medicine.

Creative Biostructure is a leading expert in structural biology analysis, offering advanced services such as cryo-EM, X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy. In addition, we specialize in the development of state-of-the-art two-dimensional surface plasmon resonance (2D SPR) microarrays, providing innovative solutions for biomedical research and diagnostics. Contact us today to learn more about our services.

References

- Ghorbel MT, Angelini GD, and Caputo M. Gene expression profiling - a new approach in the study of congenital heart disease. In: Nazari S, ed. Front Lines of Thoracic Surgery. InTech; 2012. doi:10.5772/27706

- Moncada R, Barkley D, Wagner F, et al. Integrating microarray-based spatial transcriptomics and single-cell RNA-seq reveals tissue architecture in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38(3):333-342. doi:10.1038/s41587-019-0392-8

- Parolin C, Giordani B, Ñahui Palomino RA, et al. Design and validation of a DNA-microarray for phylogenetic analysis of bacterial communities in different oral samples and dental implants. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):6280. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-06743-6

- Ramn J, Tornero-Esteban P, Fernndez-Gutirrez B. Therapeutic potential of MSCS in musculoskeletal diseases (Osteoarthritis). In: Davies J, ed. Tissue Regeneration - From Basic Biology to Clinical Application. InTech; 2012. ISBN 10: 9535103873

- Sealfon SC, Chu TT. RNA and DNA microarrays. In: Khademhosseini A, Suh KY, Zourob M, eds. Biological Microarrays: Methods and Protocols. Humana Press; 2011:3-34. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-551-0

- Sutandy FXR, Qian J, Chen C, Zhu H. Overview of protein microarrays. CP Protein Science. 2013;72(1). doi:10.1002/0471140864.ps2701s72