Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) is a widely used analytical technique that measures the absorption of infrared radiation by a sample, providing valuable insight into its molecular composition and structure. It has applications in a wide range of fields, including chemistry, biology, and materials science.

With leading technology, a professional team, and high standards of ethics and integrity, Creative Biostructure provides superior FTIR services.

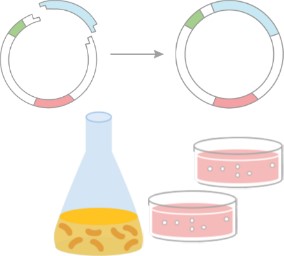

Figure 1. An example of an FTIR spectrometer with an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) attachment.

Figure 1. An example of an FTIR spectrometer with an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) attachment.

What is FTIR?

FTIR is a non-destructive spectroscopic technique used to obtain the infrared absorption or emission spectrum of a solid, liquid, or gas sample. FTIR measures the intensity of infrared light absorbed by a sample as a function of frequency or wavelength, providing information about molecular vibrations within the sample. The resulting spectrum can be analyzed to identify functional groups, chemical bonds, and molecular interactions.

Principle of FTIR Spectroscopy

The principle of FTIR is based on the interaction of infrared light with the vibrational modes of molecules. When infrared light passes through a sample, the different molecular bonds in the sample will absorb infrared radiation at specific wavelengths corresponding to their vibrational frequencies. These frequencies typically fall within the infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum (roughly 4000 to 400 cm⁻¹). In the FTIR technique, the entire spectrum is collected simultaneously using an interferometer, and then the data is processed using a mathematical technique known as a Fourier transform to convert the raw interferogram into a conventional absorption spectrum.

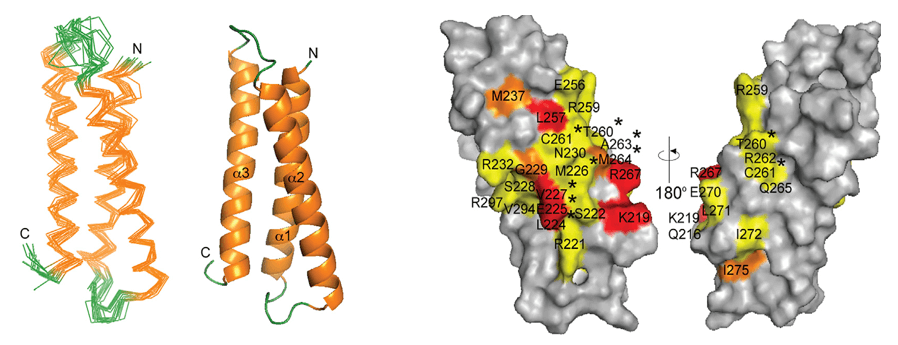

Figure 2. Principles of the Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR). (Patrizi et al., 2019)

Figure 2. Principles of the Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR). (Patrizi et al., 2019)

How an FTIR Spectrometer Operates?

An FTIR spectrometer consists of several key components that work together to collect and analyze infrared spectra:

- Infrared Light Source: This provides the infrared radiation that passes through or is reflected off the sample. Common sources include globar (for mid-IR) or quartz-halogen lamps (for near-IR).

- Interferometer: The interferometer is a key component of the FTIR system that splits the light from the source into two beams that are then recombined to create an interferogram. This process allows all wavelengths of infrared light to be collected simultaneously. The most common interferometer design is the Michelson interferometer.

- Sample Compartment: The sample is placed in the path of the infrared light. Depending on the sample, it may be placed in a transmission or reflection configuration. Liquid or gas samples are typically placed in sample cells with special optical windows, while solid samples can be analyzed directly or in a diffuse reflection configuration.

- Detector: After the infrared light interacts with the sample, the transmitted or reflected light is detected by a sensor. Common detectors include deuterated triglycine sulfate (DTGS) and mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) detectors.

- Computer and Fourier Transform: The raw data, in the form of an interferogram, is processed by a computer that performs a Fourier transform to convert the data into a conventional absorption spectrum.

What is FTIR Used for?

FTIR spectroscopy has a broad range of applications in various scientific fields:

- Molecular Identification: FTIR is extensively used to identify chemical compounds by analyzing their characteristic absorption bands, which correspond to specific molecular vibrations of functional groups. This makes FTIR an invaluable tool in fields such as organic chemistry, pharmaceuticals, and material science.

- Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis: FTIR is used for both qualitative and quantitative analysis. It is particularly useful for determining the composition of complex mixtures, detecting impurities, and monitoring chemical reactions.

- Biological Applications: FTIR is used to study proteins, lipids, and other biomolecules, allowing researchers to study conformational changes, protein folding, and interactions. It is also used to characterize biomaterials and to study disease-related changes at the molecular level.

- Environmental Monitoring: FTIR can detect and quantify gases in the atmosphere, making it an essential tool in environmental monitoring. It is used to study pollutants and measure atmospheric composition.

FTIR in Structural Biology

FTIR plays an essential role in structural biology, particularly in the study of conformational changes and interactions of biomolecules such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. By analyzing the infrared absorption bands associated with functional groups (e.g., amide I and II bands in proteins), FTIR provides insight into protein folding, secondary structure, and dynamics.

Protein Secondary Structure Analysis

FTIR detects the characteristic amide I (1600–1700 cm⁻¹) and amide II (1500–1600 cm⁻¹) bands, which corresponding to the C=O and N-H vibrations in peptide bonds, and deconvolution of these bands reveals the secondary structure composition. Specifically, α-helices are observed around 1650 cm⁻¹, β-sheets appear at approximately 1630 cm⁻¹ for parallel and 1680 cm⁻¹ for antiparallel configurations, while random coils are typically found around 1645 cm⁻¹. FTIR is applied to quantify structural changes during protein folding and unfolding, and it is also used to assess the stability of therapeutic proteins, such as antibodies and enzymes, under various stress conditions like pH and temperature.

Conformational Dynamics and Ligand Binding

- Time-Resolved FTIR: This technique can capture real-time structural changes that occur during enzymatic reactions or ligand binding events, making it a powerful tool for studying dynamic biological processes. For example, during ATP hydrolysis in kinases, FTIR can track the transient changes in vibrational frequencies associated with phosphate groups, providing insights into enzyme catalysis and conformational changes.

- Ligand-Induced Shifts: When a ligand binds to a biomolecule, changes in absorption bands reflect changes in hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, or charge distribution. These shifts can be used to monitor drug binding to target proteins, such as G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), and reveal how ligands modulate receptor activation and signaling pathways. By detecting subtle spectral changes, FTIR can help characterize ligand selectivity, affinity, and binding mechanisms.

Membrane Protein and Lipid Bilayer Studies

- Lipid Analysis: FTIR spectroscopy can distinguish between different lipid phases—gel-like or liquid crystalline—by analyzing the C-H stretching modes in the 2800–3000 cm⁻¹ range. These spectral features provide insights into acyl chain ordering, fluidity, and phase transitions in lipid bilayers, which are critical for understanding membrane dynamics and function.

- Membrane Proteins: FTIR is particularly useful for studying conformational changes in α-helical transmembrane domains, such as those found in rhodopsin, a light-sensitive membrane protein involved in vision. By tracking shifts in the amide I and amide II bands, researchers can study the structural rearrangements that occur upon activation, interaction with ligands, or changes in membrane composition.

- Sample Prep: The use of Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR)-FTIR allows for the analysis of hydrated lipid bilayers or intact cell membranes without requiring extensive sample preparation or drying. This preserves the native environment of membrane proteins, enabling accurate characterization of their structure and function under physiological conditions.

Nucleic Acid Structure and Interactions

- DNA/RNA Backbone: Phosphodiester stretching vibrations in the 1220–1250 cm⁻¹ range provide valuable information on nucleic acid conformations, distinguishing between B-DNA, Z-DNA, and A-DNA forms. These spectral markers are essential for studying structural transitions in response to environmental conditions, binding interactions, or chemical modifications.

- Ligand Binding: FTIR can detect the binding of small molecules to DNA and RNA, such as minor groove binders (e.g., Hoechst dyes) or intercalators (e.g., ethidium bromide), by observing spectral shifts in nucleobase and backbone vibrations. This capability is critical for drug discovery, as it helps identify compounds that selectively target genetic material for therapeutic applications.

Pathological Aggregates and Disease Biomarkers

- Amyloid Fibrils and Protein Aggregation: FTIR is a valuable tool for characterizing β-sheet-rich protein aggregates, which are hallmarks of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. The presence of strong amide I signals around 1620–1640 cm⁻¹ is indicative of amyloid fibril formation, providing a means to study aggregation kinetics and the effects of potential inhibitors.

- Biomedical Diagnostics: FTIR spectroscopy can differentiate between cancerous and healthy tissue based on lipid and protein spectral signatures. Changes in the amide and phospholipid regions serve as biomarkers of malignancy, making FTIR a promising technique for early disease detection and histopathologic analysis.

Complementing High-Resolution Techniques

- Synergy with X-ray Crystallography and Cryo-EM: While X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) provide high-resolution static structures, FTIR adds valuable dynamic and environmental context. For example, it can validate flexible loops in crystallographic models by detecting conformational flexibility that may not be apparent in static snapshots.

- Quality Control: FTIR is an essential quality control tool before conducting cryo-EM or NMR experiments. It ensures that samples maintain their structural integrity, proper folding, and functional state, preventing artifacts or misinterpretations in downstream structural studies.

Advantages and Limitations of FTIR

| Advantages of FTIR | |

|---|---|

| Sample Flexibility | Analyzes solids, liquids, gels, and films with minimal preparation. |

| Non-Destructive | Preserves samples for downstream analyses. |

| High Sensitivity | Detects microgram quantities, ideal for scarce biological samples. |

| Limitations of FTIR | |

| Sample Preparation | Some samples, particularly those that are very thick or heterogeneous, may require careful preparation to ensure accurate results. |

| Water Interference | Water strongly absorbs infrared radiation, leading to interference in measurements of hydrated samples. |

| Low Sensitivity for Certain Compounds | FTIR may not be as sensitive as other spectroscopic methods, such as mass spectrometry, for detecting very low concentrations of compounds. |

| Overlapping Peaks | Complex mixtures may exhibit overlapping absorption peaks, making it challenging to resolve individual components. |

Select Service

Case Study

Case 1: A combined Far-FTIR, FTIR Spectromicroscopy, and DFT Study of the Effect of DNA Binding on the [4Fe4S] Cluster Site in EndoIII

Endonuclease III (EndoIII) is a DNA glycosylase involved in base excision repair (BER) and contains a [4Fe4S] cluster that is essential for binding to damaged DNA. This study proposes that double-stranded DNA (ds-DNA) binding alters the covalency and strength of Fe-S bonds in the cluster due to electronic structure changes. Micro-FTIR and far-IR FTIR spectroscopy were used to study structural changes in EndoIII and its [4Fe4S] cluster upon ds-DNA binding. Vibrational modes corresponding to Fe-S (sulfide) and Fe-S (thiolate) bonds were identified and analyzed using quantum chemical calculations. The study found that the negative charge of DNA shifts these vibrational modes, modifies the Fe-S bond lengths, and stabilizes the cluster in a higher oxidation state (3+), facilitating redox communication along the DNA helix.

![A combined Far-FTIR, FTIR spectromicroscopy, and DFT study of the effect of DNA binding on the [4Fe4S] cluster site in EndoIII.](/upload/image/5-4-2-9-guide-to-fourier-transform-infrared-spectroscopy-ftir-3.jpg) Figure 3: Micro-FTIR spectroscopy of the EndoIII/ds-DNA complex (a) Image showing the distribution of the EndoIII/ds-DNA complex film immobilized on a gold-coated glass substrate. The area marked in red is selected for 3D imaging and extraction of spectra; (b) chemical image showing the distribution of the amide-I spectral band intensity with an inset showing a 3D image of the red-highlighted area in (a–c) spectra selected from two different regions A and B of the sample, located as shown in the inset; (d) Array of spectra extracted from several pixels of the image. (Hassen et al., 2020)

Figure 3: Micro-FTIR spectroscopy of the EndoIII/ds-DNA complex (a) Image showing the distribution of the EndoIII/ds-DNA complex film immobilized on a gold-coated glass substrate. The area marked in red is selected for 3D imaging and extraction of spectra; (b) chemical image showing the distribution of the amide-I spectral band intensity with an inset showing a 3D image of the red-highlighted area in (a–c) spectra selected from two different regions A and B of the sample, located as shown in the inset; (d) Array of spectra extracted from several pixels of the image. (Hassen et al., 2020)

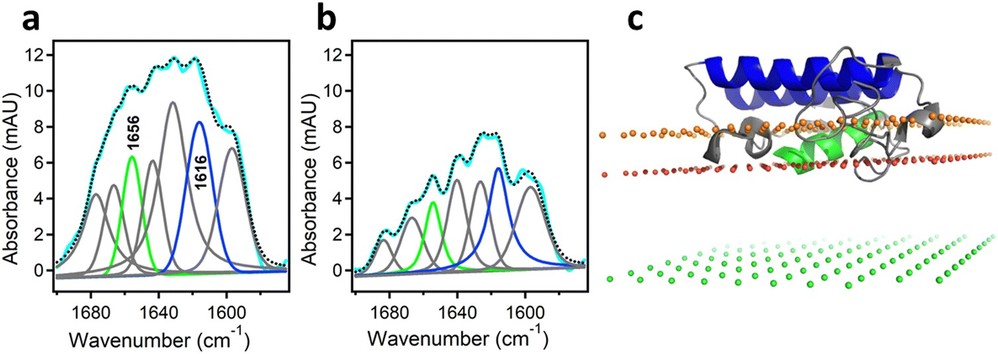

Case 2: Analysis of Protein–Protein and Protein–Membrane Interactions by Isotope-Edited Infrared Spectroscopy

This work highlights the power of isotope-based Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy to address key biochemical, biophysical, and biomedical challenges, particularly in protein-protein and protein-membrane interactions essential to life processes. It provides an overview of how isotopic substitutions affect spectral frequencies and intensities, and demonstrates the use of isotope-labeled proteins and lipids to study enzymatic mechanisms, membrane binding of peripheral proteins, regulation of protein function, aggregation, and structural changes during functional transitions.

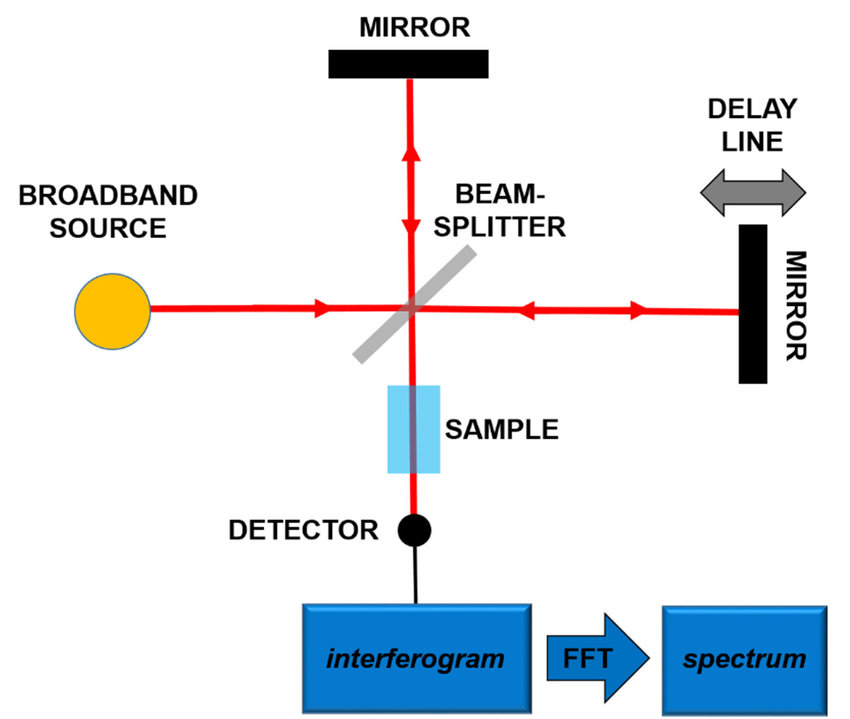

Figure 4: Determination of the orientation of a membrane-bound protein by polarized ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. (a) and (b) ATR-FTIR spectra of membrane-bound human pancreatic PLA2 with unlabeled N-terminal helix and 13C-labeled fragment at coplanar (a) and orthogonal (b) polarizations of the incident light with respect to the plane of incidence. The measured spectrum is shown in cyan and the sum of all amide I components is shown as dotted black line. The amide I components generated by the unlabeled and 13C-labeled helices are shown in green and blue, respectively. (c) The structure of the protein bound to the membrane with its N-terminal and internal helices shown in green and blue, respectively. The three planes indicate the locations of the membrane center (green), the sn-1 carbonyl oxygens (red) and the phosphate atoms (orange) of the lipid. (Tatulian, 2024)

Figure 4: Determination of the orientation of a membrane-bound protein by polarized ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. (a) and (b) ATR-FTIR spectra of membrane-bound human pancreatic PLA2 with unlabeled N-terminal helix and 13C-labeled fragment at coplanar (a) and orthogonal (b) polarizations of the incident light with respect to the plane of incidence. The measured spectrum is shown in cyan and the sum of all amide I components is shown as dotted black line. The amide I components generated by the unlabeled and 13C-labeled helices are shown in green and blue, respectively. (c) The structure of the protein bound to the membrane with its N-terminal and internal helices shown in green and blue, respectively. The three planes indicate the locations of the membrane center (green), the sn-1 carbonyl oxygens (red) and the phosphate atoms (orange) of the lipid. (Tatulian, 2024)

Creative Biostructure offers comprehensive Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy services, providing precise molecular analysis for a wide range of applications. Our advanced FTIR techniques enable the identification of chemical structures, characterization of biomolecules, and investigation of molecular interactions with high sensitivity and accuracy. Contact us today to discuss your research and analytical requirements

References

- Ami D, Sciandrone B, Mereghetti P, et al. Pathological ATX3 expression induces cell perturbations in E. Coli as revealed by biochemical and biophysical investigations. IJMS. 2021;22(2):943. doi:10.3390/ijms22020943

- Hassan A, Macedo LJA, Souza JCP de, Lima FCDA, Crespilho FN. A combined Far-FTIR, FTIR spectromicroscopy, and DFT study of the effect of DNA binding on the [4fe4s] cluster site in EndoIII. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1931. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-58531-4

- Patrizi B, Siciliani De Cumis M, Viciani S, D'Amato F. Dioxin and related compound detection: perspectives for optical monitoring. IJMS. 2019;20(11):2671. doi:10.3390/ijms20112671

- Tatulian SA. Analysis of protein–protein and protein–membrane interactions by isotope-edited infrared spectroscopy. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2024;26(33):21930-21953. doi:10.1039/D4CP01136H